Archive for the ‘spirituality’ Category

A Week − Thoreau’s Spiritual Odyssey

“Bear in mind. Child, and never for an instant forget, that there are higher planes, infinitely higher planes, of life than this thou art now travelling on. Know that the goal is distant, and is upward, and is worthy [of] all your life’s efforts to attain to.” (Journal, vol. II, 497)

HENRY DAVID THOREAU, alas, is too often seen as almost a one-hit-wonder. Walden is revered as a great work of literature. His second most famous work, On Civil Disobedience, is respected, but almost more as a political manifesto than as literature per se. Few read his poems, journals or essays.

Yet there is good reason to regard A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers as a literary masterpiece equal to, if not even surpassing Walden.

It was not received well on its initial publication, and Thoreau re-wrote it twice. Even the third version, published at his own expense, fared poorly: the publisher sent 3/4 of the volumes back to him unsold.

The work was plainly a labor of love for Thoreau. He spent nearly a decade on it. Emerson thought highly of it, but the critics did not. They complained of its unorthodox style — a travel narrative interspersed with various anecdotes, poems and ‘stray’ philosophical thoughts.

In the 20th century a more favorable view emerged. People began to see that everything in A Week was connected. There is a sublime unity, and the theme is spirituality. It is not a literal narrative of a journey up and down a river, but a parable for the soul’s journey, its immortal destiny. Lawrence Buell devotes a chapter to it, referring to Thoreau’s aim “to immortalize the excursion, raising it, in all its detail, to the level of mythology,” and calling it the “most ambitious literary work the Transcendentalist movement produced” (p. 144).

Thoreau used the story of his trip with his brother John — who died tragically not long after the events — to work through his grief, and arrive at a firm hope in a life beyond this one. Moreover, as artist, poet and prophet, he wished to communicate a deep message to his readers.

Whether A Week is a great work, whether he succeeded like the ancient Greek poets he so admired in producing an immortal work, I leave it up to you to decide. But it is a beautiful and haunting work in any case. The spiritual dimension is superbly revealed by Klaus Ohlhoff in his master’s thesis. I have never seen a thesis more insightful and artistically composed than this. Chapter 2 ought to have been published as a standalone essay, but apparently never was.

Trust me. If you love Thoreau (and many do, of that I am certain), you will appreciate this Ohlhoff’s chapter. I will not spoil it by quoting from it, nor cite or relevant passages from A Week. If you’ve ever read A Week or ever plan to — I would simply urge you to read Ohloff’s study.

References

Adams, Raymond W. Thoreau and Immortality. Studies in Philology, vol. 26, no. 1, 1929, pp. 58–66.

Bishop, Jonathan. The Experience of the Sacred in Thoreau’s Week. ELH, 33, March 1966.

Buell, Lawrence. Literary Transcendentalism: Style and Vision in the American Renaissance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973; Chapter 8, Thoreau’s A Week (pp. 208−238).

Ohlhoff, Klaus W. Thoreau’s Quest for Immortality. Diss. Lakehead University, 1979; Chapter 2 (pp. 63–144).

Paul, Sherman. The Shores of Africa: Thoreau’s Inward Exploration. Urbana; University of Illinois Press, 1958.

Thoreau, Henry David. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. New York: Crowell, 1911.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

July 19, 2022 at 1:42 am

Posted in American Transcendentalism, Americana, Idealism, Philosophy, Plato, Reading, spirituality, Transcendentalism

Tagged with American Literature, Henry David Thoreau, immortality, mystical experience, mythology, Thoreau, transcendence

Inspired Literature (reposted)

Simone Cantarini, Saint Matthew and the Angel, Italian, 1612 – 1648, c. 1645/1648, oil on canvas.

IN ONE of his more famous writings, William Ellery Channing addressed the topic of developing a uniquely American intellectual tradition. His message is important today in several respects. One of his chief concerns was to counter the growing tide of materialism in Europe and America. This, he believed, could only end in, at the individual level, unhappiness, and, at the collective level, dehumanizing institutions and dysfunctional government. Sound literature, he maintains, is founded on genius, which is itself activated when our hearts and minds are aligned with our moral and spiritual nature. Genius does not manifest itself in a vacuum, however: inspired writers write inspiredly when there is an audience capable of receiving an inspired message. Hence our first need is to morally prepare the public. This, Chandler, argues, is the proper role of religion. But religion itself must be of a higher quality. Instead of religion based on formality, authority, dogma or superstition, we need one based on personal spiritual experience and authentic moral consciousness. . . . read full article here (re-posted from my Christian Platonism blog)

Written by John Uebersax

July 13, 2022 at 1:14 am

Posted in American Transcendentalism, consciousness, Cultivation of the Intellect, Cultural psychology, Culture, Idealism, Literature, Materialism, Moral philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, religion, Renewing America, Scholarship, Self-culture, Social philosophy, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values

Tagged with Genius, Inspiration, religious experience, religious reform, William Ellery Channing

Dial (1840−1844) − Complete Edition

THE seminal New England Transcendentalist periodical Dial, published from 1840 through 1844, is a milestone in the history of American literature, philosophy and intellectual life. It’s something not only of historical interest, but a living part of American consciousness. The ideas were to lofty to have much direct impact then, but they await and invite rediscovery by new generations.

To the best of my knowledge, the complete four volumes have never been printed in their entirety, except for a very limited edition in 1902. Moreover, many of the fine essays and poems do not exist in machine readable form. I have hopefully met the need by taking four scanned volumes available from Google Books, converting them with optical character recognition to machine readable form, placing them in a single, bookmarked pdf file, and adding author information not in the original volumes. The free pdf ebook can be downloaded here.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

June 28, 2022 at 2:10 am

What American Transcendentalism is Not

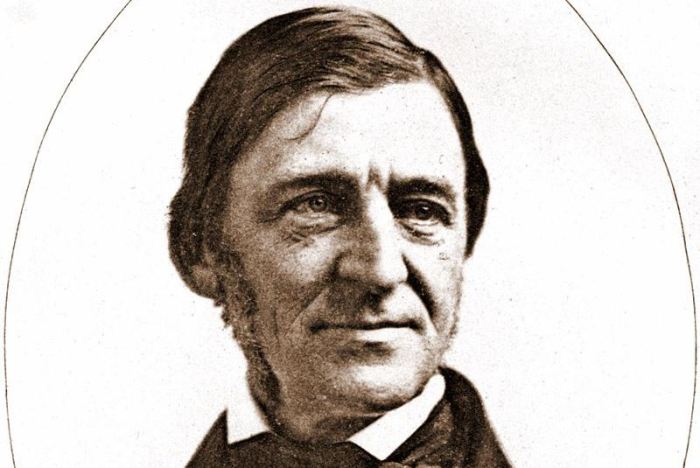

Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1859

THERE is today in the United States a severe cultural crisis that involves a loss of morale, hope and meaning. This probably affects most of all young adults, who have their whole lives ahead of them, and yet must face problems like student loan debt, lack of adequate jobs, unaffordable housing, and completely dysfunctional politics, coupled with an absence of meaningful creativity in literary and artistic sectors of society.

Behind all these problem is a more fundamental one: that the cultural mentality in the West today is one of radical materialism — and materialism, by its very nature, robs life of true meaning. If radical materialism is the malady, then a return to cultural Idealism is the remedy. No only common sense, but also — as we have often discussed at Satyagraha — the theories and historical research of the sociologist Pitirim Sorokin give us some grounds for optimism that a more Idealistic society may emerge from modern materialism.

One way to promote a return to Idealism is to re-familiarize ourselves with the great tradition of American Transcendentalism. This has several advantages. First, Transcendentalism[1] is an indigenous, Americanized Idealism, peculiarly suited to our own unique circumstances, history and potentials as a nation. Second (and partly for the preceding reason), while it has faded from view, it has merely been submerged rather than entirely eliminated from the collective consciousness — as evidenced by such examples as that, even if nobody bothers to read them, we still name streets after Emerson and Thoreau and their portraits hang in the halls of university English Departments.

Young adults today, then, ought to understand what American Transcendentalism is. Then they will at least know there is a coherent and achievable alternative to a materialistic culture. One obstacle, however, is that explaining Transcendentalism (or even defining the term) is notoriously difficult. Part of the problem is that we are dealing with a cultural mentality, including states of consciousness, which are by their nature ‘intangible’ and therefore inherently difficult to literally define.

However perhaps we can be clever here, and approach the issue indirectly. That is, let’s try here not to define what Transcendentalism is, but what it isn’t. That will get us partway to the goal, and in the process can help eliminate certain specific misconceptions that may impede gaining a proper understanding.

Turning, then, to that supremely authoritative source of misinformation, the Google search page, we see that in response to the question “What is American Transcendentalism” it says: “Key transcendentalism [sic] beliefs were that: (1) humans are inherently good but can be corrupted by society and institutions; (2) insight and experience are more important than logic; (3) spirituality should come from the self, not organized religion; and nature is beautiful and should be respected.”

Let’s look at each statement in turn and examine how it is true, false, incomplete, or potentially misleading.

Humans are inherently good but can be corrupted by society and institutions.

The bland statement ‘humans are innately good’ is something more like Rousseau would say. Transcendentalists held much stronger beliefs: that humans are divine, with immortal souls and godlike potentials. We are, as Emerson put it, ‘gods in ruins.’ That is, we fail to live up to our divine potential. The proper remedy is moral, intellectual and spiritual self-culture. Each individual has a solemn moral duty for such self-cultivation.

To say that human beings’ corruption comes from society and institutions is, again, Rousseauian. For Transcendentalists, it is we are ourselves who are to blame for our failures. In a characteristically Platonic fashion (Plato is the dominant philosophical influence on Transcendentalists), the human soul is understood as fallen — not because of external forces, but from insufficient personal virtue and wisdom. Transcendentalists certainly wished to reform and make more just government and society. But this supposes that a free individual can elevate himself or herself to be an agent of change, despite the opposing influences of current institutions.

Insight and experience and more important than logic.

This is basically true, but incomplete. Transcendentalists saw themselves as reacting to the narrow rationalist mentality associated with John Locke and his followers. This empirical/rationalist worldview became increasingly dominant throughout the 18th and into the 19th century. It created, in the opinion of Transcendentalists, a mechanical perspective of life — a utilitarian society where money counts more than meaning, the end always justifies the means, and atheism displaces religion in human affairs.

It is also true that Transcendentalists highly valued ‘experience.’ They saw modern man as living life abstractly — one step removed from reality (as Emerson put it, “living second-hand.”) We respond not to things as they are, about according to rational theories that are, by their nature, limiting and distortive.

Similarly, insight was vital for Transcendentalists. This is an essential feature of Idealism, generally. Insight pertains to realms of knowledge we have that have no connection with the sensory or material world, but instead concern what we see about our own nature by looking within.

Spirituality should come from the self, not organized religion.

Implicit in this statement — but it needs to be stated explicitly — is that Transcendentalists staunchly affirmed that spirituality ought to be central in our lives. As to the view of organized religion, Transcendentalists were divided on this point. Some, like Emerson and Thoreau, had little use for organized religion. Others, however, maintained affiliations with the Unitarian and, in some cases, Congregational or Episcopal denominations.

The central issue is not organized religion, but dogmatized religion. The essential point Transcendentalists wished to affirm (which is the same affirmation made by mystics of all religious throughout the ages) is that personal spiritual experience matters more than imposed literal doctrine. A preacher or catechism can insist, “God is Love” — yet that carries far less force than having the direct experience of God as Love. In the final analysis, doctrine and personal experience are not mutually exclusive. Doctrine can be useful in order that, as St. Augustine taught, belief may lead to experience. However what is clear — and is the real issue here — is that an overemphasis on doctrine has the potential to crowd out and lessen the potential for direct religious experience.

Nature is beautiful and should be respected.

Again, this is a weak and even revisionist version of what Transcendentalists actually believed. To say that ‘nature is beautiful’ would hardly distinguish them from any other movement or segment of humanity. What they actually believed — and what does make them relevant today — are stronger propositions: (1) that Nature has a spiritual basis; (2) that it is a manifestation of God, and of God’s Goodness and Love; (3) that it is also an externalization of our own soul; (4) and that Nature is like a book, intended in every detail to teach us spiritual lessons.

Therefore Nature should indeed be ‘respected’ — but not merely in the sense of that modern environmentalists might understand this. We should most respect Nature precisely because it is a means of understanding (and relating to) God and ourselves. This necessarily implies a strong commitment to protect the natural environment; indeed, it increases our incentive to do so.

Moreover, we must not only respect Nature, but experience it. So, for example, while we should preserve forests and wildernesses, part of the reason for doing this is so that we can visit and receive inspiration from them. To merely preserve and completely isolate from all human contact some natural area, while something a modern environmentalist may consider, would make much less sense to a Transcendentalist.

In sum, the main difficulty here is that any 20th or 21st ‘official’ definition (such as might appear in an online article or university text) of Transcendentalism will necessarily be revisionist. Materialism is so strongly engrained in the modern cultural mentality that one cannot explain Idealism without sounding superstitious or atavistic. There is some kind of unwritten consensus that we are not allowed to conduct serious public discussions on the premises that God exists and the human soul is immortal. Yet without these premises Transcendentalism and Platonic Idealism cannot be understood or appreciated. American Transcendentalism, then, is a great challenge to modernism: it starkly confronts us with the arbitrariness of the assumptions of materialism and atheism. It shows us that a great generation of thinkers were able to develop from these premises a philosophy of life both meaningful and with far-reaching practical significance.

Another important issue with the simplified description of Transcendentalism we’ve considered here is the omission of any reference to the literary interests of this group. These were not people who merely had ecstatic nature experiences. Almost without exception they applied themselves to make significant contributions to literature and education, and to the moral edification of others. Integral to the Transcendentalist personality was the notion of harnessing the creative inspirations and energies of ‘innate genius’ in productive ways to actively contribute to the positive transformation of society.

In the near future I hope to try again to write a brief post dedicated to positively defining the key beliefs of Transcendentalism, but let this suffice for now. Ultimately, the main way to understand it is to read main works of Transcendentalist literature. Some recommended selections may be found in the Bibliography of this earlier article.

Note. 1. Herein for convenience the terms ‘American Transcendentalism’ and ‘Transcendentalism’ are used interchangeably; there are, of course, other versions of transcendentalist or Transcendentalist philosophy.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

June 19, 2022 at 9:35 pm

Posted in American Transcendentalism, consciousness, Cultivation of the Intellect, Cultural psychology, Culture, Idealism, Literature, Materialism, modernism, Moral philosophy, Philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, Plato, Renewing America, Self-culture, Social philosophy, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values

Tagged with mystical experience, transcendence

The Four Psychological Responses to Great Social Crises

THE sociologist Pitirim Sorokin conducted extensive research on cultural mentalities, including comprehensive historical studies (Sorokin 1957, 1985). He found that major shifts in mentality are often precipitated by the occurrence of multiple crises and catastrophes — wars, plagues, famines, natural disasters, revolutions, etc. He also noted that the crises developing in the 20th century — which he correctly predicted would worsen — would likely necessitate or precipitate a major change in cultural mentality. Hopefully, in his view, this would be a shift from radical materialism to a more idealistic, altruistic, transcendent and integrated mentality.

One of his papers (Sorokin, 1951) identified four responses to “mass-suffering and mass-frustration in social calamities.” These apply at both the individual and collective psychological level. In brief terms, the four responses are as follows:

Passivity. Faced with crises they are powerless to oppose or remedy, individuals succumb to a state of passive resignation, depression, and hopelessness. This is probably the most widespread response.

Degradation. Here the individual responds by becoming more aggressive, brutal and selfish. In the case of wars and revolutions, the person ‘identifies with the aggressor.’ The world is accepted as a bellum omnium contra omnes. Virtue is abandoned, and escape and solace are sought in various vices and follies: sex, addiction, avarice, fanaticism, chronic anger, etc. Demoralization leads to self-loathing, and further self-destructive flight into vice and delusion.

Heroism. A few individuals endowed with extraordinary resilience and talent seek to defiantly meet the social challenges with heroic feats of creativity. In the artistic realm, Beethoven serves as an example, and Edison in the scientific/technical arena.

Moral reformation. The most productive response in Sorokin’s opinion, is exemplified by the lives of great saints and reformers who appear throughout history, often in times of crisis and catastrophe. However, while great figures like St. Francis of Assisi and Mohandas Gandhi are rare, the same process of moral reformation they underwent is played out less visibly in the lives many more ‘ordinary saints.’ In each case, the trajectory of moral reformation is basically the same: first the individual acknowledges the seriousness of their own moral failings, admitting and rejecting the innate selfishness and aggression of lower human nature (repentance; metanoia). Then, by characteristic practices such as asceticism, meditation and prayer, they seek to purify themselves from these failings, and then to grow in altruism and spirituality. During this process, they reject former social roles built on egoistic values and develop new ones based on spiritual values — often going through a period of relative (or sometimes complete) isolation in between. Finally, with egoism conquered, they direct their energies with clear purpose and absolute focus on altruistic, charitable and creative activities aimed at improving the lives of others. Part of this altruistic activity may involve helping others to achieve this same moral transformation.

When, perhaps under the stimulus of some exemplary figure like St. Francis or Gandhi, many individuals in society undergo this moral reformation, the mentality of the entire culture shifts from the materialistic and egoistic to the altruistic.

In short, it was Sorokin’s hope and vision (see especially, Sorokin 1948, 1954) that, as the crises of the 20th century continued and worsened, this transformation of culture would occur. He argued that not only is this possible — as this transformation has occurred in the past — but it may be necessary today for the continuation of the human race.

Yet, even apart from the broader cultural significance, it must be remarked that this form of altruistic and spiritual transformation is something of supreme value for the individual. Repentance and conversion are not an onerous burdens, but gateways to joy, self-realization, and liberation of the divine potentials — the arrival at our full stature as human beings. It is within our power, then, as individuals, to cognitive reframe the meaning and significance of the crises of our times. In crises lay great opportunities.

References

Sorokin, Pitirim A. The Reconstruction of Humanity. Beacon Press, 1948.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. Polarization in frustration and crises. Archiv Für Rechts- Und Sozialphilosophie, vol. 39, no. 2, 1951, pp. 145–163.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. The Ways and Power of Love: Types, Factors, and Techniques of Moral Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1954; repr. Templeton Foundation, 2002. [ebook]

Sorokin, Pitirim A. Social and Cultural Dynamics. Revised and abridged in one volume by the author, Transaction Books, 1957, 1985. (Originally published in four volumes, I–III, 1937; IV, 1941.)

❧

Written by John Uebersax

May 6, 2022 at 1:38 am

Posted in consciousness, Cultural psychology, Culture, Gandhi, higher consciousness, Humanism, humanistic psychology, Idealism, Love, Materialism, Moral philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, Psychology, Social philosophy, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values

Tagged with altruism, catastrophes, cultural mentality, ethics, moral renewal, social crises, social transformation

Gods in Ruins

NEEDED at this point in history is a great leap forward in human consciousness, a new way of looking at ourselves — as individuals and collectively. This weekend I had a glimpse of what this leap might look like, and am still trying to sort it out, but I’ll attempt here to convey the essence.

The idea is suggested by a phrase from Ralph Waldo Emerson, “We are gods in ruins.” This sentence has quite a bit of meaning. First, we are gods. That’s plausible enough. Christians and members of other religions believe that human beings are made in God’s image and likeness. Each person is an image of God, and has an eternal souls and has unlimited, divine potentials.

But, Emerson added: in ruins. We may have the potential to be divine, but our thoughts and actions are, with rare exceptions, anything but that.

But consider how different the world would be if each person remained constantly aware that (1) all other persons are divine; and (2) each person was falling short of their divine potential.

Now let’s now add love to the formula. Each person has the potential to love another human being in a divine and godly way. We can recall times when we’ve felt loved and can remember the many and immense benefits this feeling has. And we ourselves can, in theory, love any other human being in this way, producing the same divine positive effects. Your love can work miracles in another person’s life, and theirs can work miracles in yours. Few things if any make us feel better than to be loved. You have the power to produce that feeling in any one of 7 billion other souls on the planet; and there are 7 billion souls who have the ability to have that effect on you.

Consider what I’m saying here. What if, instead of love, we were talking about money. Suppose I said that you have the ability to make any one (and perhaps any number) of the 7 billion people on this planet a millionaire. And 7 billion people had the power to do that for you. What a colossal waste it would be, then, if we had this power and never used it, such that the vast majority of the world’s population lived in poverty!

One might say that surely humanity is not so foolish as to let that happen. Yet consider that love is more valuable than money. A rich person without love is miserable, whereas a poor person with love is happy. The greatest advantage money has, in fact, is to produce circumstances favorable for the flourishing of love. Yet, for the most part, money is not needed for love. Seen in this way it is incredible how we are ignoring this vast ‘natural resource’ of love. It is being utterly wasted.

Now let’s put the two ideas together: the notion of ‘gods in ruins’ and the untapped potential of love. What if each person habitually thought as follows:

- Each other person on the planet is an image of God.

- Each other person has divine, untapped potentialities, a principle one being the capacity for divine love and altruism.

- We are all falling short of this potential.

- What if I could do something — anything — to help other people be restored to their divinity and use their divine potentialities? How could I better employ my time and energies than to do this? What would make me feel more satisfied?

- What is more divine than to love divinely? What if I could do something to help another person love divinely?

First we should note that this view is more true than our ordinary consensual concept of what it is to be human. If we are gods in ruins, then we should think of ourselves as such. It would make us less egoistic, anxious, foolish, selfish, frivolous, scattered, and angry. We would soon discover many ways to help other people. And also consider how, were such thinking to become the norm, it would change our perception of society. What if we had a culture in which it was pre-supposed that other people value the image of God in you, and are not only willing but eager to help you realize it? It seems clear that a society based on these values would be vastly superior to our present one, and would reduce or eliminate many of the crippling social problems we now face (beginning with war).

For millennia religions have taught us that we are divine beings — and humanity has chosen to pretend otherwise. Now we may have no choice but to rise to our full stature.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

May 2, 2022 at 5:00 am

Posted in Anti-war, consciousness, Cultural psychology, Culture, Culture of peace, higher consciousness, Humanism, humanistic psychology, Idealism, Love, Materialism, Peace, religion, Social philosophy, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values, War

Tagged with altruism, ethics, social transformation

Pitirim Sorokin: The Role of Religion in the Altruistic Transformation of Society

IN 1948, in the aftermath of two colossally destructive world wars, the dropping of atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the commencement of the Cold War, Harvard sociologist wrote The Reconstruction of Humanity. He saw as few others did the perilous road that lay ahead. Certainly others sounded a warning bell, but Sorokin’s sweeping studies of cultural history gave him deeper insight into the problems of modern society — and the possible solutions — than others.

What he foresaw was a continued decay of society obsessed with materialism and sensate values. The only solution, he believed, was to consciously renew culture on the principles of idealism and altruism. The first half of Reconstruction of Humanity he devoted to debunking false panaceas of popular democracy, science, capitalism, world government and the United Nations. In the second half he presented his prescription, which involved an intentional restructuring of the family, education and religion — all with the explicit aim of raising consciousness and fostering the development of a deep transformation of human personality from egoism to altruism.

The following comes from his section on religion. He saw modern religions as needing to concentrate efforts on two fundamental reforms: (1) a greater emphasis on religious experience (as opposed to doctrine), and (2) achieving a greater proportion of practitioners who see religion as central, not merely peripheral to their lives.

Sorokin, though a sociologist, was quite sophisticated in his understanding of religion. Large sections of his work, The Ways and Power of Love are devoted to the Western monastic system and Indian yoga as means of effecting a thorough moral and psychological transformation of the individual.

The message of Reconstruction of Humanity (which, incidentally, was dedicated to Mohandas Gandhi) is more relevant and urgent today than ever.

III. Religious Institutions

Religion is a system of ultimate values and norms of conduct derived principally through superconscious intuition, supplemented by rational cognition and sensory experience. As such it tends to constitute the supreme synthesis of the dominant values and norms of conduct. Its superconscious intuition makes us aware of, and puts us in contact with, the superconscious aspect of the ultimate reality value, the Infinite Manifold, God, or the Holy. Herein religion is little dependent upon logic and sensory experience. In so far as it attempts to give a rational and empirically correct synthesis of the superconscious, the rational, and the empirical aspects of the Infinite Manifold, it draws upon syllogistic and mathematical logic and upon empirical science.

Virtually all the major religions and all genuine religious experiences have apprehended the ultimate reality value in a very similar way so far as its superconscious aspect is concerned. The differences between the Tao of Taoism, the “Heaven” of Confucianism, the Brahman of Hinduism and Buddhism, the Jehovah of Judaism, the God of Christianity, and “the Inexpressible” of mystics consist mainly in differences of terminology, in the accentuation of this or that aspect of the Infinite Manifold, and in the even more subsidiary differences of rationalized dogmas and cults. In these secondary traits religions vary and undergo change; in their intuition of the ultimate reality value as an Infinite Manifold, as in their basic values and norms of conduct, they remain essentially unchangeable. The scale of values of all genuine religions unanimously puts at the top the supreme value of the Infinite Manifold itself (God, Brahman, Tao, the Holy, the Sacred), and then, in descending order, the highest values of truth, goodness, and beauty, their inferior and less pure varieties, and finally the sensory and sensate values. Likewise, the moral commandments of all genuine religions are fundamentally identical. Their ethics is the ethics of unbounded love of man for God, for his fellow men, for all living creatures, and for the entire universe. In brief, in their intuitive system of reality — values and norms of conduct, religions remain true to themselves, undergoing little change, and depending little upon logic and empirical knowledge.

In their rational and empirical ideologies religions, as has been said, naturally depend upon logic and empirical science. Since these are incessantly changing, religions change also in these respects: in their theological rationalizations, in their cult and ritual, in their empirical activities and organizations. If a religion does not modify these logical and empirical elements in conformity with changes in logical and sensory knowledge (mathematics, logic, and science), it becomes obsolescent in these components and is eventually supplanted by a religion whose logical and empirical values and norms are up to date. The superconscious essence of the supplanting and the supplanted religion remains, however, essentially the same. Religion as a superconscious intuition of the Infinite Manifold is perennial and eternal; as a rationalized system of theology, as an empirical system of cult, ritual, and technical activities, it is incessantly changing.

There has been scarcely any great culture without a great religion as its foundation. The emergence of virtually all notable cultures has been either simultaneous with or preceded by the emergence of a notable religion which has constituted its most valuable component. The decline of any major culture or the end of one era and the beginning of a new era in its life history has again been marked by either the decline of its religion, or by a replacement of one religion by another. Only eclectic cultural congeries have been devoid of an integrated system of religion. Such cultural congeries have functioned mainly as material to be used by creative cultures. Without Confucianism and Taoism the Chinese culture is unthinkable; without Hinduism and Buddhism there would have been no great Hindu culture; without the Greek religion and philosophy Greek culture would have been impossible; without Mohammedanism there would have been no notable Islamic-Arabic culture; without Zoroastrianism the Iranic culture could not have achieved a high level. The same relationship applies to the Egyptian, Babylonian, Judaistic, and Western Christian cultures and religions.

If we wish to build a truly great culture, we must create or recreate one or several great systems of ultimate reality — values and norms of conduct for the various parts of the human race. Like different languages, each denoting the same objects in its own words and idioms, humanity may have different “religious languages,” each in its own way conveying the experience of the Holy, putting men in touch with the Infinite Manifold, and constituting the indispensable condition of the creativity of their culture and of a peaceful, altruistic social system.

Viewed in this light, the existing major religions, Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Mohammedanism, Jainism and others, do not urgently need to be replaced by new religions or to be drastically modified. Their intuitive system of reality value (God, Brahman, Tao, etc. as an Infinite Manifold) and their conception of man as an end value, as a son of God, as a divine soul, as a bearer of the Absolute; these intuitions and conceptions are essentially valid and supremely edifying (in varying degrees for the different religions).

Similarly, their ethical imperatives, enjoining a union of man with the Absolute and an unconditional love of man for his fellows and for all living creatures, call for no radical change. Some of these norms, such as those of the Sermon on the Mount, are, indeed, incapable of improvement.

What is needed, therefore, concerns not the essence of the great religions but its revitalization and the modification of their secondary traits.

It is essential to recover a vital sense of the living ‘presence of God, of union with the Infinite Manifold, such as has been experienced by the mystics and other deeply religious persons. This experience should not be attended by the emotional outbursts and bodily convulsions typical of many present-day “revivals.” A large proportion of contemporary believers hardly ever enjoy such an experience. Their religiosity is chiefly a formal adherence to the prescribed ritual and cult, a mechanical repetition of traditional formulas, the mere outer shell of religion without its living flame. Hence their religious ideologies scarcely influence their overt conduct.

This reawakening of intense religious experience is inextricably connected with the actual application, in overt behavior, of the ethical norms of religion. The transformation of overt conduct in the direction of ‘practicing what one preaches’ is another fundamental change that must he effected by the leading religions. We have seen that in modem times there has appeared an unbridgeable chasm between avowed beliefs and standards, on the one hand, and their embodiment in actual practice on the other. Thus the adherents of Christianity overtly behave, as a rule, in the most un-Christian manner. Since they retain but the formal shells of their religion, devoid of its real substance, such a chasm is inevitable.

The revitalization of religion consists precisely in these two essential tasks:

(1) re-creation of a genuine religious experience;

(2) realization of ethical norms in the overt behavior of the believers.A truly religious person, feeling vividly the presence of God, walks humbly and reverently on this earth and loves the other children of God and all living creatures to his utmost capacity.

These are the paramount needs of religious transmutation. Believers, especially religious leaders, must concentrate their efforts on these tasks instead of devoting most of their energy to the external shells of religiosity; their cult and ritual, [note 1] their institutional property and hierarchy, their rational theology and dogmas, their politics and their claims for the superiority of their own brand of religion over the others.

The sacredness of man as an end value and the ethical commandments enjoining love are limited in several religions to the circle of their own believers. This tribal provincialism, with its double standard of morality, should cease. Any true religion of the future must he universal in the sense that everyone, regardless of his race or nationality, creed, age, sex, or status, is regarded as a sacred end value.

Its logical and empirical aspects, which are incessantly changing and whose validity depends upon logical and empirical science, religions must bring into harmony with existing science and logic, dropping what is obsolescent. This concerns theological speculation and dogma, cult and ritual, and the technique of man’s spiritualization and moralization. Keeping abreast with logic and science in these subsidiary features, religion enters into harmonious co-operation with science, logic, and philosophy without sacrificing any of its intuitive truth revealed through the superconscious of its seers, prophets, and charismatic leaders. On the other hand, in its turn it supplements science, logic, and philosophy through its system of ultimate reality — values. In this way religion, logic, science unite to form a single harmonious team dedicated to the discovery of the perennial values and to the proper shaping of man’s mind and conduct.

For the realization of these objectives religions need not only to be familiar with existing techniques but also to create new, more fruitful, and more adequate techniques of religious and ethical transformation. (Cf. the next section of this work for an elaboration of this topic.) [note 2]

If the foregoing tasks are successfully performed, religion will contribute as never before to the creation of a society characterized by peace and harmony, happiness, and a sense of kinship with the Infinite Manifold.

Notes.

1. Sorokin’s comments here might be mistakenly understood to mean he does not appreciate the importance of religious ritual. Rather, I believe his point is that these should be understood not as ends in themselves, but as powerful tools that support and enhance the fuller spiritual life of the practitioner.

2. His later and more definitive analysis of techniques for altruistic transformation of society is found in Sorokin (1954/2002).

Bibliography

Sorokin, Pitirim. The Reconstruction of Humanity. Beacon Press, 1948.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. Social and Cultural Dynamics. Revised and abridged in one volume by the author, Transaction Books, 1957, 1985. (Originally published in four volumes, I–III, 1937; IV, 1941.)

Sorokin, Pitirim A. The Ways and Power of Love: Types, Factors, and Techniques of Moral Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1954; repr. Templeton Foundation, 2002. [ebook]

❧

Written by John Uebersax

April 19, 2022 at 4:29 am

Posted in Anti-war, Catholicism, Christianity, consciousness, Cultural psychology, Culture, Culture of peace, Gandhi, higher consciousness, Humanism, humanistic psychology, Idealism, Love, Materialism, Militarism, Peace, Pitirim Sorokin, religion, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values, War, Yoga

Tagged with altruism, ethics, religious experience, social transformation

The Soul’s Vast Battle of Kurukshetra

PREVIOUSLY I’ve suggested (Uebersax, 2012, 2017) that a useful framework for understanding the psychological meanings of ancient myths is subpersonality theory (Lester, 2012; Rowan, 1990). Three leading hypotheses of this view are: (1) the human psyche can be meaningfully likened to a city or kingdom with many citizens (a situation which opens up many allegorical possibilities); (2) individual ‘citizens’ of the psyche may take the form of psychological complexes; and (3) there may potentially be a very large number — thousands or millions — of these mental citizens operating. These hypothesis were derived by applying subpersonality theory to interpretation of the myths of the Old Testament (following hermeneutic principles laid down by Philo of Alexandria 2000 years ago), and Plato’s Republic (a work that makes much more sense interpreted as an allegory for the psyche than as a literal manual for civil politics.)

Independent confirmation of these hypotheses is found in a recent commentary on the Bhagavad Gita by Swami Kriyananda. Relevant passages are shown below. The Bhaghavad Gita is a section of the much larger work, the Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata. The Mahabharata describes a vast battle on the plains of Kurukshetra between two clans, the Panduvas and the Kauravas. Allegorically, the Panduvas symbolize our virtues, and the Kauravas our vices. Hence the epic falls into the category (and is perhaps the most notable example) of a psychomachia myth, comparable with such Greek myths as the Titanomachy (the battles of the Olympian gods against the Titans) and the Trojan War (as mythologically chronicled in Homer’s Iliad), and with the Old Testament’s various battles and contentions between the Israelites and their enemies.

Swami Kriyananda’s allegorical interpretation of the Mahabharata follows a tradition imparted to him by his teacher, Paramhansa Yogananda (1893−1952), who either inherited or derived it from the teachings of his guru, Swami Sri Yukteswar (1855−1936) — who, in turn, was influenced by his teacher, Lahiri Mahayasa (1828−1895). While terms like “complex” are clearly modern, the basic psychological mechanisms described seem firmly planted in the yogic tradition.

Citizens of the Soul

The Bhagavad Gita presents a fascinating picture of human nature. It shows that every individual is a nation unto himself, his “population” consisting of all his qualities, both good and bad. … Over time, the innumerable experiences he encounters in life, and the way he encounters them, may develop in him innumerable “complexes.” In other words, certain aspects of his nature may insist on attack, while other aspects plead, tortoise-like, for a self-protective withdrawal. Still others may mutter helplessly in the background about “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” while still others spread a whispering campaign of malicious gossip to get “the world” to side with them, while another whole group of mental citizens may [plead] … for tolerance, forbearance, amused acceptance, or calm non-attachment. (pp. 47−48)

There may be thousands or even millions of such complexes/citizens:

[O]ur qualities assume the characteristics of individual personalities, as we become steeped in them by a repetition of the acts that involve us in them. Because of habit, they become entrenched as true “citizens” of our own nation of consciousness. … Thousands or millions of “citizens” mill about, each one bent on fulfilling his own desires and ambitions. Sigmund Freud hardly scratched the surface …. Freud saw only the conflict between personal desire and the expectations of society. In reality the case is infinitely more complex. (p. 50)

Ranged against his upwardly directed aspirations are innumerable downward-moving tendencies which he himself created by past wrong actions, and developed into bad habits. … the forces for error are “innumerable,” whereas the forces of righteousness are “few in number.” Countless are the ways one can slip into error, even as the outside of a large circle has room for taking many approaches to the center. Uplifting virtues are few, for they lead into, and are already close to, the center of our being. Hatred can be defined in terms of countless objects capable of being hated, whereas kindness springs from the inner self, and bestows its beneficence impersonally on all. (p. 58)

Personality Integration

That we have all these inner citizens doesn’t per se necessitate constant inner conflict, although in the usual ‘fallen’ human condition that does seem to be the case. We need not, however, suppose that the only resolution to conflict is for our virtues to utterly destroy hosts of opposing tendencies. Rather, the goal should be one of harmonization.

One obvious strategy, then, is to try to transform, convert or sublimate recalcitrant complexes. This is perhaps symbolically represented in Plato’s Cave Allegory, where, after the philosopher rises from the cave of ignorance, he voluntarily returns to try to educate and uplift the prisoners who remain there (Republic 7.519d−520e).

Another strategy is to consciously solicit the responses of multiple subpersonalities before embarking on some course of action:

introspection (Sanjava) is the wisest course to understanding. … if by introspection one canvasses the reactions of his own mental citizens, he will have a clearer understanding of what he ought or ought not to have done and of how he ought to behave in future. (p. 58)

This corresponds well to suggestions made by Rowan (1990) in managing conflicting subpersonalities.

Indispensable in any case — and this appears to be a key message of the Bhagavad Gita — is to withhold a strong ego-identification from any particular complex. It is not really complexes themselves that cause conflict, but only when we mistakenly identify them as who we are.

Further study and application of subpersonality to the interpretation of myths seems warranted. Modern psychologists can learn much about personality integration and self-realization by studying the Indian mythological epics such as the Mahabharata, Bhagavad Gita, and the Ramayana. Indian myths, Greek myths, the stories of the Old Testament, and even Plato’s Republic can be understood using a common set of hermeneutical principles. They supply multiple maps of a common terrain, the human soul. Their messages — salvation of the soul by means of Wisdom, virtue, holiness and, above all, love of God — are the same.

first draft 27 July 2021

References

Assagioli, Roberto. Psychosynthesis. London: Turnstone, 1975.

Swami Kriyananda. The Essence of the Bhagavad Gita Explained by Paramhansa Yogananda. Crystal Clarity Publishers, 2008. ebook audio book

Lester, David. A Multiple Self Theory of the Mind. Comprehensive Psychology, 2012, 1, 5.

Rowan, John. Subpersonalities: The People Inside Us. London, 1990.

Uebersax, John. Psychological Allegorical Interpretation of the Bible. Paso Robles: El Camino Real Books, 2012.

Uebersax, John. Psychopolis: Plato’s Inner Republic and Personality Theory. Satyagraha weblog. 12 January 2017.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

July 27, 2021 at 11:10 pm

Posted in consciousness, False opinion, higher consciousness, humanistic psychology, Idealism, Literature, Mind-Body, Moral philosophy, Philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, Plato, Plato's Republic, Psychology, religion, spirituality, The Republic, Yoga

Tagged with Bhagavad Gita, Indian philosophy, Mahabharata, Old Testament, Paramhansa Yogananda, Philo of Alexandria, subpersonalities, subpersonality theory, Swami Kriyananda

Václav Havel: Living in the Truth as the Remedy for the New Totalitarianism

Abrilliant 1978 essay by Czech dissident/president Vaclav Havel has five key takeaway messages for the present crises in American politics. These relate to: (i) post-totalitarianism as a new form of mass subjugation; (ii) the expansively bureaucratic nature of post-totalitarianism; (iii) ideology as its central pillar; (iv) conformity as essential for its continuance; and (v) possible solutions — most importantly, a realignment of individual and cultural values to what he called “living in the truth“.

These are briefly explained below, though no short summary does adequate justice to Havel’s insightful and well-written essay. (See Readings for links to free versions.)

1. Post-totalitarianism

By post-totalitarianism Havel meant a new form of totalitarianism that has emerged in the modern era. If differs from “classical dictatorship” in several respects. First, whereas classical dictatorships are unique, historical aberrations — often based on a cult of personality — post-totalitarianism is rooted in the history of ideas (e.g., draped in the mantle of 19th century socialist theories and Enlightenment political liberalism);

Second, as a government system, post-totalitarianism outlives changes in political leaders and ruling parties:

a post-totalitarian system, after all, is not the manifestation of a particular political line followed by a particular government. It is something radically different: it is a complex, profound, and long-term violation of society, or rather the self-violation of society. To oppose it merely by establishing a different political line and then striving for a change in government would not only be unrealistic, it would be utterly inadequate, for it would never come near to touching the root of the matter.

Third, whereas classical dictatorships use direct force to oppress and control the masses, post-totalitarianism uses indirect methods (see ‘Conformity’ below).

Fourth, means of overturning classical dictatorships, including revolution and elections, are ineffective here.

Even if revolt were possible, however, it would remain the solitary gesture of a few isolated individuals and they would be opposed not only by a gigantic apparatus of national (and supranational) power, but also by the very society in whose name they were mounting their revolt in the first place. (This, by the way, is another reason why the regime and its propaganda have been ascribing terroristic aims to the “dissident” movements and accusing them of illegal and conspiratorial methods.)

2. Bureaucracy

Post-totalitarianism takes the form of an expansive and omnipotent bureaucracy. It begins with the government itself, but enlarges to assimilate business, news and communication media, education, and cultural institutions. Fundamentally amoral and unprincipled, its main aim is to preserve itself and to expand. Any threat to its power is met with savage (and inevitably effective) opposition.

3. Ideology

Havel’s insights about the role of ideology in post-totalitarianism are one of the essay’s greatest contributions. Ideology supplies two main functions in a post-totalitarian system: excusatory and administrative.

Excusatory function. First, it’s the means by which the bureaucracy legitimizes itself:

Ideology is a specious way of relating to the world. It offers human beings the illusion of an identity, of dignity, and of morality while making it easier for them to part with these.

Ideology, [creates] a bridge of excuses between the system and the individual … a world of appearances trying to pass for reality.

The primary excusatory function of ideology, therefore, is to provide people, both as victims and pillars of the post-totalitarian system, with the illusion that the system is in harmony with the human order and the order of the universe.

It enables people to deceive their conscience and conceal their true position and their inglorious modus vivendi.

It supplies a veil behind which human beings can hide their own fallen existence, their trivialization.

Administrative function. Second, ideology supplies the means by which a totalitarian system organizes and communicates with itself.

Ideology plays a central role in the complex machinery of the post-totalitarian system. It supplies indirect instruments of manipulation which ensure in countless ways the integrity of the regime, leaving nothing to chance.

Ideology offers a fundamental world view, with which to interpret every event, activity and entity in the world of human affairs. It supplies virtually a “metaphysical order” that “guarantees the inner coherence of the totalitarian power structure,” and “integrates its communication system and makes possible the internal exchange and transfer of information and instructions.”

In order for post-totalitarian ideology to operate effectively, it must reign in every area of society. No threat to it, and no opposing alternative ideology, can be permitted to emerge. Unchallenged, the ideology becomes increasingly removed from reality.

As the interpretation of reality by the power structure, ideology is always subordinated ultimately to the interests of the structure. Therefore, it has a natural tendency to disengage itself from reality, to create a world of appearances, to become ritual. In societies where there is public competition for power and therefore public control of that power, there also exists quite naturally public control of the way that power legitimates itself ideologically. [Usually] there are always certain correctives that effectively prevent ideology from abandoning reality altogether. Under [post-totalitarianism], however, these correctives disappear, and thus there is nothing to prevent ideology from becoming more and more removed from reality, gradually turning into … a world of appearances, a mere ritual, a formalized language deprived of semantic contact with reality and transformed into a system of ritual signs that replace reality with pseudo-reality.

Yet, as we have seen, ideology becomes at the same time an increasingly important component of power, a pillar providing it with both excusatory legitimacy and an inner coherence. As this aspect grows in importance, and as it gradually loses touch with reality, it acquires a peculiar but very real strength. It becomes reality itself, albeit a reality altogether self-contained, one that on certain levels (chiefly inside the power structure) may have even greater weight than reality as such. Increasingly, the virtuosity of the ritual becomes more important than the reality hidden behind it. The significance of phenomena no longer derives from the phenomena themselves, but from their locus as concepts in the ideological context. Reality does not shape theory, but rather the reverse.

Because the regime is captive to its own lies, it must falsify everything. It falsifies the past. It falsifies the present, and it falsifies the future. It falsifies statistics. It pretends not to possess an omnipotent and unprincipled police apparatus. It pretends to respect human rights. It pretends to persecute no one. It pretends to fear nothing. It pretends to pretend nothing.

4. Conformity

Yet, Havel claims, the post-totalitarian system and its tissue of lies require the tacit or active endorsement of the masses.

Individuals need not believe all these mystifications, but they must behave as though they did, or they must at least tolerate them in silence, or get along well with those who work with them. For this reason, however, they must live within a lie. They need not accept the lie. It is enough for them to have accepted their life with it and in it.

For by this very fact, individuals confirm the system, fulfill the system, make the system, are the system…

by accepting the prescribed ritual, by accepting appearances as reality, by accepting the given rules of the game. In doing so, however, he has himself become a player in the game, thus making it possible for the game to go on, for it to exist in the first place

the moment that excuse is accepted, it constitutes power inwardly

everyone in his own way is both a victim and a supporter of the system. What we understand by the system is not, therefore, a social order imposed by one group upon another, but rather something which permeates the entire society and is a factor in shaping it.

The American post-totalitarian system is especially insidious in its use of economic and other incentives to gain the support of the population and their acceptance of self-oppression.

Even progressive liberals are heavily invested in the status quo (and even literally so, as they see their retirement portfolios grow while the Dow Jones Industrial Average increases year after year, regardless of the injustices Wall Street perpetrates to ensure profits. The public is addicted wholesale to social media like Twitter, Facebook and YouTube, which collude with the security state. A large proportion of jobs exist within oppressive corporations and government institutions.

5. Solutions

If the essence of post-totalitarianism is construction of a false reality, and if the people themselves maintain the system by living a lie within it, then, Havel argues, the only real solution is for people to begin again living in the truth.

A genuine, profound, and lasting change for the better — as I shall attempt to show — can no longer result from the victory (were such a victory possible) of any particular traditional political conception, which can ultimately be only external, that is, a structural or systemic conception. More than ever before, such a change will have to derive from human existence, from the fundamental reconstitution of the position of people in the world, their relationships to themselves and to each other, and to the universe. If a better economic and political model is to be created, then perhaps more than ever before it must derive from profound existential and moral changes in society. This is not something that can be designed and introduced like a new car. If it is to be more than just a new variation of the old degeneration, it must above all be an expression of life in the process of transforming itself. A better system will not automatically ensure a better life. In fact, the opposite is true: only by creating a better life can a better system be developed.

There is an emphasis on the word “living” here. Havel does not mean paying lip service to the truth, or raging against lies. Living in the truth is an existential solution that occurs first at the individual level, and then at a cultural level. Words, manifestos, articles and books are not enough. The revolution is an accumulation of individual shifts in personal consciousness, to experiential anamnesis of the True, the Beautiful and the Good.

Part of the solution, Havel argues, is dissent — but (and this is very important) only certain forms of dissent. Many forms of dissent are ineffective and counter-productive.

An essential part of the “dissident” attitude is that it comes out of the reality of the human here and now. It places more importance on often repeated and consistent concrete action — even though it may be inadequate and though it may ease only insignificantly the suffering of a single insignificant citizen — than it does in some abstract fundamental solution in an uncertain future.

Another form of living in the truth is legal challenges. Legal challenges are, so to speak, an Achilles’ heel of the post-totalitarian system, because it needs to legitimize itself in laws.

In other words, is the legalistic approach at all compatible with the principle of living within the truth? This question can only be answered by first looking at the wider implications of how the legal code functions in the post-totalitarian system. In a classical dictatorship, to a far greater extent than in the post-totalitarian system, the will of the ruler is carried out directly, in an unregulated fashion. A dictatorship has no reason to hide its foundations, nor to conceal the real workings of power, and therefore it need not encumber itself to any great extent with a legal code. The post-totalitarian system, on the other hand, is utterly obsessed with the need to bind everything in a single order: life in such a state is thoroughly permeated by a dense network of regulations, proclamations, directives, norms, orders, and rules. (It is not called a bureaucratic system without good reason.)

Like ideology, the legal code functions as an excuse. It wraps the base exercise of power in the noble apparel of the letter of the law; it creates the pleasing illusion that justice is done, society protected, and the exercise of power objectively regulated.

Because the system cannot do without the law, because it is hopelessly tied down by the necessity of pretending the laws are observed, it is compelled to react in some way to such appeals. Demanding that the laws be upheld is thus an act of living within the truth that threatens the whole mendacious structure at its point of maximum mendacity.

They have no other choice: because they cannot discard the rules of their own game, they can only attend more carefully to those rules. Not to react to challenges means to undermine their own excuse and lose control of their mutual communications system.

But more than anything else Havel understands living in the truth as something apolitical. The root problem is that we are a false society composed of false selves. We must concentrate on creating a new, authentic culture, one person at a time.

Above all, any existential revolution should provide hope of a moral reconstitution of society, which means a radical renewal of the relationship of human beings to what I have called the “human order,” which no political order can replace. A new experience of being, a renewed rootedness in the universe, a newly grasped sense of higher responsibility, a new-found inner relationship to other people and to the human community — these factors clearly indicate the direction in which we must go.

In other words, the issue is the rehabilitation of values like trust, openness, responsibility, solidarity, love.

In view of this, how ironic it is that since Havel’s time a different paradigm of regime change has prevailed in Eastern Europe. Instead of living in the truth, the US (via the CIA), globalized corporations, and dubiously-aligned NGOs have used covert activities and mass propaganda to not only to impose changes of government, but to assassinate truth.

Comparison with Sorokin

Havel’s ideas here invite comparison with those of Pitirim Sorokin, who also called for a moral reconstruction of humanity in responses to the crises of modern culture. While their views are similar, Sorokin (armed with his massive historical studies of human culture) arguably delved more deeply into what such a reconstruction would look like, and how it might be accomplished. For one thing, he was much more aware of the role of traditional spirituality in effecting such changes. He also placed great emphasis on the experience of Love (agape) as a central positive cultural value. Finally, Sorokin understood that ultimately solutions must come from higher sources of inspiration — the supraconscious. Without strong or definite religious convictions, Havel — for all his excellencies — could only grope in the dark about matters of spirituality. He agreed that rationalism itself could supply no answers, but could only discuss transcendence in vague terms (e.g. Havel, 1993). More than once Havel quoted the words of Heidegger, to the effect that in the crises of modernity “Only a God can save us now.” Whereas Havel could leave this as no more than a poetic expression, Sorokin could carry it to is logical conclusion: “Fortunately, there is a God, to whom we should turn.”

Note: Quotations have been edited and rearranged in places; please compare with original source before excerpting anything.

Readings

Havel, Václav. The power of the powerless. Paul Wilson, tr. In: John Keane (ed.), The Power of the Powerless: Citizens Against the State in Central Eastern Europe, M. E. Sharpe, 1985. Orig. publ. in International Journal of Politics, vol. 15, no. 3/4, 1985, pp. 23–96. [pdf version] [plain text version]

Havel, Václav. The need for transcendence in the postmodern world. The Futurist, July−August 1995. Speech delivered in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, July 4, 1994.

Sorokin, Pitirim. The Reconstruction of Humanity. Boston: Beacon Press, 1948.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. The Ways and Power of Love: Types, Factors, and Techniques of Moral Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1954; repr. Templeton Foundation, 2002. [ebook]

Related posts

- Abraham Maslow: How to Experience the Unitive Life

- A Meditation on Man’s Transcendent Dignity

- Beyond the Pyramid. Being-Psychology: Maslow’s Real Contribution

- Culture in Crisis: The Visionary Theories of Pitirim Sorokin

- Pitirim Sorokin: Techniques for the altruistic transformation of individuals and society

- Transcendentalism as Spiritual Consciousness

Written by John Uebersax

July 15, 2021 at 9:34 pm

Posted in alienation, Art, Cognitive psychology, consciousness, Cultivation of the Intellect, Cultural psychology, Culture, Culture of peace, Europe, False opinion, Gandhi, Globalization, higher consciousness, History, Humanism, humanistic psychology, Humanities, Idealism, Love, manufacture of consent, Materialism, Media brainwashing, modernism, Moral philosophy, News, News bias, Occupy Movement, Peace, Philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, Plato, Political parties, Politics, propaganda, Psychology, Public opinion, Reform in government, Renewing America, Self-culture, Social justice, Social philosophy, spirituality, Statism, Totalitarianism, Transcendentalism, Values

Tagged with 2020 election, Agape, altruism, Corporatism, creativity, cultural transformation, Inspiration, prayer, supra-conscious, tech oligarchs, Vaclav Havel

Pitirim Sorokin: Techniques for the Altruistic Transformation of Individuals and Society

OUR earlier article about Pitirim Sorokin (Culture in Crisis) explained the crises of modern culture as he understood them. Especially in the wake of the Covid pandemic, it’s evident that, since that article was written (over a decade ago), crises have multiplied and intensified. It’s appropriate, then, that we now direct attention more closely to the solutions Sorokin proposed. Whereas in the past cultural transitions have occurred at the whim of chance and Fate, we must now, he argued, think in terms of intentional change, of active steps to produce an Idealistic culture. This would involve a simultaneous transformation of individuals and society, but with the former as more primary.

Under the rubric of “Idealism” Sorokin understood the broad Platonic view of the unity of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful. Inseparable from these, he believed, is the principle of Love. For personal and social transformation, Sorokin placed primacy on Love.: “An increase in our knowledge of the grace of love has become the paramount need of humanity.” It is to the topic of stimulating and harnessing Love as a transforming power that he devoted arguably his greatest and most mature work, The Ways and Power of Love. The book represents a summary and distillation of research conducted at his Harvard Research Center in Creative Altruism in the early 1950s.

An Authentic and Scientific Understanding of Love

The word, ‘love,’ of course, has many meanings. The kind of love that interested him in this research is agape — unselfish or disinterested (not uninterested) love or loving-kindness. Agape love is to be explicitly distinguished from sentimentalism. It’s something loftier, gentler and more hopeful than feelings of pity or compassion. Nothing captures this distinctiveness better than the words of St. Paul (which Sorokin cites):

1 Corinthians 13 (KJV)

[1] Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.

[2] And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing.

[3] And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.

[4] Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up,

[5] Doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil;

The Greek word translated as charity here is agape.

Even more, agape love is to be distinguished from that righteous indignation often expressed as angry, even violent action performed in the name of love, compassion, and justice. It is also not to be confused with expansive government social programs and bureaucracy. Although properly-administered government programs serve valid purposes, they are no substitute for agape love and individual actions performed for its sake.

In the end, for cultural transformation to be truly aligned with agape love, interventions must, Sorokin argued, be inspired and directed by a realm of truth and knowledge superior to that given by merely rationalistic modes of thought. The closing section will discuss Sorokin’s pivotal concept of the supraconscious.

Techniques for Altruistic Transformation

Drawing on many sources, including historical research, biographies of great moral reformers, studies of ordinary ‘good samaritans,’ and consultation with other social scientist, Sorokin included in Part 4 of Ways and Power an extensive analysis of alternative means for altruistically transforming individuals and Society. The complete list is here. He was emphatic that no single solution would work:

The foregoing chapters clearly show that altruistic formation and transformation of human beings is an exceedingly delicate, complex, and difficult operation. There is no single magic procedure that can successfully perform it. Neither is there a standard set of operations equally applicable to all persons and groups. To be effective, the methods must vary in accordance with the many conditions and properties of the individuals and groups. In addition, even the effective method must be supplemented and supported by a respective transmutation of the culture and social institutions of the persons and groups undergoing the altruistic change.

Below are essential extracts from four techniques he discussed that have special relevance to themes discussed at Satyagraha.

Altruization Through Fine Arts and Beauty

Fine arts can and do serve the task of altruistic ennoblement as well as that of cognition of truth. … By its nature the fine art masterpiece represents a marvelous unity which arouses simultaneously our intellectual, emotional, affective, volitional, and vital energies. … Art can teach many … suprarational truths which cannot be communicated by words and concepts. … [A] masterpiece of painting or sculpture, the Parthenon or a great cathedral, uplifts us in the realm of creative spirit more efficiently than a statistical diagram, mathematical formula, or a chain of impeccable syllogisms can do. …

In mankind’s great and rich treasury of art masterpieces, however, including the beauty of the sunset, of starry skies, and of millions of natural phenomena, there always can be found the special art medium fit for altruistic transfiguration of a given person or group. Sometimes it lies in ‘the small voice’ of the sun reflected in a pool of water, or in a little tune of a beautiful folksong or in the joyful play of children, not to mention the chefs-d’oeuvre of the great artists and masters. With discernment the fine arts can and should be used much more than they are used now, for mental, moral, and the ‘total’ education of mankind. Additional merit of this technique is that it works in a most enjoyable way, free from the pains and fatigue of many other techniques. (Ways and Power of Love, Ch. 17)

Altruization Through Individual Creative Activity

The creative urge represents the focal point of human personality. … great creative achievements are inspired by the supraconscious and are executed by the conscious mind working under the guidance of the supraconscious genius which resides in the creative person. In a small degree the voice of the supraconscious speaks also in modest creative efforts. The creative urge is thus in a sense the holy of holies of every person. It is also the most distinctive mark of his individuality, of his conscious egos, and especially of his egoless self. Creativity and individuality both mean something new, something different from what already exists and from other persons. … a free display of the creative urge is one of the main forms of man’s freedom. Free manifestation of the creative urge is therefore one of the main ingredients of man’s happiness, self-respect, and peace of mind. Frustration of the creative urge means an undermining of his individuality, his freedom, and his happiness….

[The creative] individual or group is deflected from many mischiefs, squabbles, and enmities by the much more absorbing creative thoughts and deeds. The very nature of their constructively creative work tends to ennoble them mentally and morally. They increasingly become the instrument of the best conscious activities and of the supraconscious forces, and decreasingly the animal organisms controlled by discordant biological drives and by disharmonious, narrow egos. …

[A frustrated creative instinct] is possibly one of the important factors in … unrest, and interindividual, intergroup, and international tensions — war included — of our age. … The widening [of creative opportunities] is urgently needed not only for altruistic purposes and for mitigation of our ‘wars of everyone against everyone,’ but also for physical and mental welfare and the cultural progress of humanity. After all, “the Supreme Creator” is possibly the most important characteristic of God. Creativity is also the most important life mission of man. It is man’s royal road to the supraconscious, as well as of the supraconscious to man. It [unites] the mortal human being with the Immortal Cosmic Creator. Why then not open this royal road for all human beings? (Ways and Power of Love, Ch. 17)

Altruization Through Private and Public Prayer

Prayer is one of the most accessible and fruitful ways for spiritualization and altruization of human beings and groups. The more of this sort of prayer, the better for all of us. Supplication, worship, prayer are no superstition; they are acts more real than the acts of eating, drinking, sitting or walking. It is no exaggeration to say that they alone are real. …

The main objective of … prayer is a dissolution of one’s lilliputian egos, interests, and aspirations in the “Thy will be done,” in the infinitely greater Supreme Being, however it is called and conceived. Altruistic prayer strives to free the supraconscious in man from the shackles of his little egos for the union with the Supreme Supraconscious. Such prayer tends to turn our organism and our unconscious and conscious mind into an instrument of the supraconscious in us and, through that, of the Cosmic Supraconscious. …

[Pierre] Marinier correctly remarks that: “It is a discipline for unification of self with self and self with the world. Modern man often claims to reject it because it appears in conjunction with creeds or dogmatic conceptions to which he cannot adhere. But psychological value of prayer is independent of these creeds in their dogmatic form. … Modern man by refusing to pray deprives himself of the most fecund forces from his past and from his secret being. These forces remain unused, even repressed, while the individual, whose consciousness is no longer linked to the universal, flounders at the superficies of himself in an illusion of liberty — which conceals profound dissociation and despicable ignorance. For the vast majority of us, prayer meanwhile remains the only (I would say one of the few) practical road to physical and moral recovery, to reconciliation with our ancestors, to comprehension and acceptance of the real, to liberty itself….” (Ways and Power of Love, Ch. 18)

Altruization Through Contemplation and Meditation

In [contemplation] words, verbal terms, and concepts cannot help much; if anything, they can rather mislead by replacing the total living grasp of the inexpressible whole by one of its differentiations embodied in verbal definition. For these reasons [it] is often going on in silence, without any words or verbal concepts. …

It is at the moments when the ‘chosen and anointed’ are possessed by the supraconscious that the great religions are born, the eternal moral verities are uttered, the superhuman moral deeds are done, the true prophecies are spoken, the incurables are cured, the hopeless sinners are redeemed, the moral and spiritual mission of humanity is set forth, and its foundations are laid down.

What is still more significant here is the fact that many of these [heroes of spirituality and love] discover, teach, and practice their verities without a serious labor of their conscious mind …. The hour of the supraconscious grace over, they … are often surprised at the thoughts, words, and deeds done by them in the state of supraconscious [contemplation] and creativity. …