Archive for the ‘modernism’ Category

What is American Transcendentalism?

Bottom line. The core tenets of American Transcendentalism: (1) human beings have a higher, spiritual nature; (2) all people have common, innate Ideals (what things are True, Beautiful, Just, and Good?) and this is of vast importance for society; (3) life has definite moral meaning; (4) Nature can help connect us with God and with our own higher nature; and (5) we have supra-rational forms of knowledge: intuition, Conscience, higher Reason, inspiration, and creative imagination. Transcendentalism is a development of the Western intellectual tradition (Plato, Socrates, etc.), and places considerable emphasis on intellectual and moral self-culture. (Just walking around in the woods is not Transcendentalism!) Transcendentalism per se is compatible with Christianity, and there were in fact many Christian Transcendentalists.

I’ve written this because I take pity on the many college students who struggle each year with the obligatory English term paper on American Transcendentalism. I’m also motivated by the belief that, when your generation or a later one is ready for the challenge, it will find in Transcendentalist writings a well-developed ideology for changing the corporatist/globalist/materialistic status quo.

Transcendentalism might seem virtually incomprehensible, but it’s actually very common-sense. The difficulty is precisely that it conflicts with the received opinions and disordered thought patterns of modern culture. In other words, the irony is that Transcendentalism, as taught and written about today in the modern academic establishment, is presented through the lens of the very materialistic values it opposed! The inevitable result is a selective, distorted, revisionist, and confused picture. The aim here is so supply a more accurate portrayal.

1. Transcendentalism was an explicit reaction against the modern rationalism of philosophers like John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. The effect of these rationalist philosophies was to deny that human beings had innate knowledge and Higher Reason (or Conscience), and that people were divine — made in the ‘image and likeness of God.’ In short, rationalism led to materialism and loss of higher values.

2. The rationalist philosophy came just at the time of the Industrial Revolution. Rationalism, by denying transcendent values, justified reducing society to a vast a system of factories and banks where man is nothing but a cog in a machine. By claiming that man is merely a material creature (i.e., a machine himself), rationalism led to all the abuses of a radically commercial society. The social problems of modernity we see today actually began around 1790 in Europe and America. The Transcendentalists (and their allies, the Romanticists) understood this problem and tried to counter it.

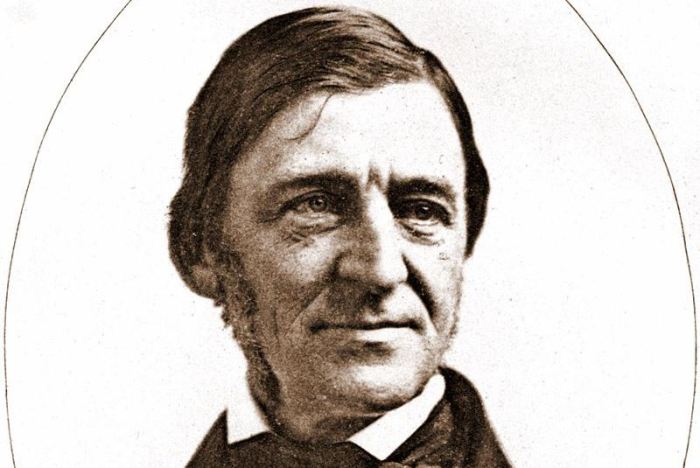

3. American Transcendentalism was a revival of the Platonic heritage of the Renaissance. Transcendentalism, Emerson, is heavily indebted to Platonism and Neoplatonism, and the Greek tradition generally (Emerson tutored in Greek; Thoreau translated Aeschylus!) Modern scholars have strangely lost sight of this. Instead, it became trendy in the 20th century to see Eastern (Indian and Persian) religions as dominant influences on American Transcendentalism. Eastern religions had a little effect, but nowhere near as much as Platonism. In short: Transcendentalism is a continuation and extension of a long-standing Western tradition in philosophy and religion.

One important part of this is the Platonic notion of innate ideas. Locke denied that human beings have innate ideas (tabula rasa), and his view dominated Enlightenment-era thinking. Kant, however, disproved Locke: he showed that our minds are so constructed as to see reality only in terms of pre-existing categories, rules, principles, and relationships. For example, we automatically see the world in moral terms, e.g., constantly evaluating ourselves, other people, and events as good or bad, right or wrong, just or unjust. It’s innate, part of our nature.

Kant’s rejection of Locke’s rationalism generated considerable excitement in Europe and America. American Transcendentalism took this new enthusiasm for Kant, and blended it with earlier, traditional Platonist and Neoplatonist concepts. Plato, of course, is most famous for his Theory of Forms (Forms = Ideals). For example, he postulated that all human beings have common, innate Ideals concerning the nature of the True, the Beautiful, the Just, and the Good.

From this it’s just a short step to Emerson’s concept of genius and art (see Emerson’s essays, ‘Self-Reliance‘, ‘Plato‘, and ‘Shakespeare‘): Each of us has the full repertoire of intellectual, moral, and aesthetic abilities characteristic of our species. For example, each person can look at a great work of art or wonder of nature and experience a sense of profound beauty or awe. We are all, in short, geniuses by nature. It’s just a question of accessing our latent abilities. Any thought or insight that any great person has ever had, you can have too! You have all the innate equipment necessary. What makes great creative geniuses different is only that they are better able to access and communicate these innate ideas.

This is an immensely important concept, and it leads to an new vision of what human society can and should be: a community of divine individuals (“gods in ruins”, as Emerson put it), who are helping each other towards self-realization. Sometimes, because of Thoreau’s reclusive reputation and Emerson’s essay, ‘Self Reliance’ (or, rather, its title), people get the impression that Transcendentalism was only about individualism, and that it denigrated society. But, as explained there, that isn’t so. Note that Transcendentalism itself only developed within a community of like-minded individuals.

It also means that, despite the incessant, distorting propaganda of governments and the materialistic status quo, we all have an innate idea (or Ideal) of what a true, just, beautiful, and good society should and can be. If we trusted our natural inclinations, and, trusted that everybody else has these same natural inclinations, we might produce a more natural, harmonious society.

4. An example of the Platonist roots of American Transcendentalism is in the constant emphasis of the latter on self-development. The ancient principle, ‘know thyself’, is strongly emphasized. One implication of self-reliance is that you must take the initiative in developing your soul: your moral and intellectual nature. A representative example of this is the book on self-culture by James Freeman Clarke. Modern self-help/pop-psychology literature, lacking a moral focus, is greatly inferior to Transcendentalist writings on self-culture.

5. Another major root of American Transcendentalism was New England Unitarianism. The wellspring of this influence was William Ellery Channing, a mentor of Emerson, and prominent teacher, minister, and lecturer at the time. Two of Channing’s more famous essays/speeches are Likeness to God and Self-Culture.

6. Another way of looking at American Transcendentalism is that it expresses what has been called the perennial philosophy — a set of core religious and philosophical ideas that crop up again and again across cultures and throughout history. These core principles include:

- The existence of an all-powerful and loving God

- Immortality of the human soul

- Human beings made in God’s image, and progress by becoming gradually more ‘divine’

- Human beings have higher cognitive powers: Wisdom, Conscience, Genius.

- Providence: God shapes and plans everything.

- Happiness comes from subordinating our own will (ego) to God’s will, putting us into a ‘flow’ state.

- And from moral development (virtue ethics)

- All reality (our souls and the natural world) are harmonized, because all are controlled by God’s will into a unity.

- Everything that does happen, happens for a reason. Life is a continuing moral lesson.

This perennial philosophy recurs throughout the history of Western civilization as an antagonist to materialism. In modern times Locke and Hobbes express the materialist philosophy. In ancient times the Epicureans similarly advanced a materialist philosophy in contrast with the transcendent philosophies of Platonism and Stoicism.

So there is a kind of Hegelian dialectic (i.e., thesis–antithesis–synthesis process) in history between materialism and transcendentalism. For this reason, the principles of American Transcendentalism will again come to the cultural forefront eventually. Indeed, it may be necessary if modern culture is to avoid worsening crises.

Emerson and Thoreau are literally our ‘tribal’ ancestors, speaking to us with inspired wisdom for the preservation, advancement, and evolution of our culture.

7. American Transcendentalism anticipated 20th century humanistic psychology (e.g., the theories of Abraham Maslow) and modern positive psychology. However it is more inclusive than either of these two in its recognition of man’s higher, transcendental nature: man’s spiritual, moral, philosophical, intellectual, and creative elements. The paradox (and failure) of modern positive psychology is precisely that it cannot extricate itself from its underpinnings in materialist/rationalist philosophy.

8. With these great ideas, why didn’t Transcendentalism continue as a major cultural force? Partly the answer has to do with the dialectical process referred to above. In the struggle between materialism and transcendentalism, things go back and forth, hopefully always working towards an improved synthesis (i.e., not so much a circular but a spiral process).

In addition, two specific factors contributed to a receding of American Transcendentalism. One was Darwinism, which dealt a tremendous blow to religious thought in the 19th century. Religious thinkers at that time simply weren’t able to understand that science and religion are compatible. People began to doubt the validity of religion and to resign themselves to the unappealing possibility that we are nothing but intelligent apes. The second blow, perhaps much greater, was the American Civil War. Besides disrupting American society and culture generally, the Civil War represented a triumph of a newly emerging materialistic progressivism over the more spiritual and refined Transcendentalism (which sought progress by reforming man’s soul, not civil institutions). The high ideals of the Transcendental movement were co-opted by militant reformers, and this problem is still with us. Modern progressives see themselves as the inheritors of Transcendentalist Idealism, but are in reality radically materialistic in values and methods!

9. A frequent criticism of American Transcendentalism is that it lacks a theory of evil: a nice philosophy for sunny days, not much help with life’s crosses and tempests.

10. Emerson resigned his post as a Christian minister over doctrinal issues, but arguably remained what might be called culturally Christian. There were many Christian transcendentalists (e.g., Theodore Parker, Henry Hedge, James Freeman Clarke, James Marsh, Caleb Sprague Henry). Orestes Brownson (and some others) eventually converted to Roman Catholicism.

11. This brings us to what transcendental means. In fact, it has a whole range of meanings — it’s something of an umbrella term. At the most general level, transcendentalism supposes that human beings do have a higher nature (see above).

Technically, there is an important distinction between the words ‘transcendental’ and ‘transcendent’ (although in practice they are sometimes used interchangeably). ‘Transcendent’ is a broad term that can mean almost anything higher or above (e.g., God, spirituality, etc.). ‘Transcendental’ refers to the fact that, when we, say, look out and perceive the world, our actual mental experience is being filtered or conditioned. By analogy, if we watch television, all we see are the images on the screen — not the inner circuitry of the television set that produces the images. The part of ourselves that filters, conditions, and produces of our mental experience is, arguably, more our ‘real self’ than our experience itself — this could be called our transcendental nature or transcendental apparatus. What it actually is, however, is a mystery, since we don’t experience it directly. Emerson was content to simply accept our transcendental nature as part of Nature, generally.

On the other hand, ‘transcendental’ could also be understood merely as an adjectival form of the word ‘transcendent’. Thus to some extent the two terms are hopelessly confounded and we cannot insist too strongly on a definite or consistent definition.

12. Historically, the term was borrowed from the transcendental philosophy of the German philosopher, Immanuel Kant. Kant developed his philosophy in opposition to the British empiricists (Locke, Hume). Kant’s philosophy generated a great deal excitement, first in Europe. In particular, two new transcendentalist movements — one in France (Victor Cousin) and one in England (Coleridge and Wordsworth) — emerged. These movements were broadly aligned with the spirit of Kant (e.g.,. rejection of Locke), but were distinct in their ideas. English transcendentalism was (1) more Platonic (see below), and (2) more Romantic.

American Transcendentalism was aware of Kant, but it was much more closely aligned with some of Kant’s German followers (e.g., Schelling), and English transcendentalism (e.g., Coleridge).

An excellent book about Transcendentalism written by a Transcendentalist is O. B. Frothingham, Transcendentalism in New England (1876). I also recommend the chapter by Howe (2009) shown in the references below.

Here is a related paper on materialist vs. transcendentalist values in modern higher education.

Transcendentalist Works

- Channing, William Ellery. Self-Culture (1838), On War (1839)

- Cooke, George Willis (ed.). The Poets of Transcendentalism. Boston, 1903.

- Clarke, James Freeman. Self-Culture by Reading and Books (1880)

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Nature (1836), The American Scholar (1837), Self-Reliance (1841), The Poet (1841), Character (1841), The Transcendentalist (1842), Wealth (1860)

- Frothingham, Octavius B. Transcendentalism in New England (1876)

- Thoreau, Henry David. Walden (1854), Life Without Principle (1863)

Websites

- The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson (online, with search engine)

- American Transcendentalism web

- Transcendentalists

- American Transcendentalism (Washington State)

- Perspectives on American Literature – Transcendentalism

- Overview of American Transcendentalism – Martin Bickman

Books/Chapters/Papers

- Howe, Daniel Walker. Making the American Self. Ch. 7, The Platonic Quest in New England, pp. 189–211. Oxford University Press, 2009 (orig. 1997). (An earlier version appeared as: Daniel Walker Howe, The Cambridge Platonists of Old England and the Cambridge Platonists of New England, Church History Vol. 57, No. 4 (Dec., 1988), pp. 470–485.)

- Parrington, Vernon L. Main Currents in American Thought, Vol. 2, Book 3, Part 3 (The Transcendental Mind, Chapters 1-5). New York: Harcourt Brace And Co., 1927.

- Richardson, Robert D. Jr. Emerson: The Mind on Fire. University of California Press, 1995.

- Uebersax, John S. Transcendentalist Writings for the Occupy Movement. 2013.

- Uebersax, John S. What is Materialism? What is Idealism? 2014.

- Uebersax, John S. What Transcendentalism is Not. 2022.

- Wayne, Tiffany K. Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism. Infobase Publishing, 2009.

On the AAAS Report on the Humanities and Social Sciences, ‘The Heart of the Matter’

A few months ago, in June 2013, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences released a report ‘The Heart of the Matter‘ addressing the state of the humanities and social sciences in the United States today. Its conclusions were expressed as three main goals: (1) to “educate Americans in the knowledge, skills, and understanding they will need to thrive in a twenty-first-century democracy;” (2) to “foster a society that is innovative, competitive, and strong;” and (3) to “equip the nation for leadership in an interconnected world.”

The first recommendation made in connection with Goal 1 was to support “full literacy,” meaning by that an advancement of not just reading ability, but also of the critical thinking and communication skills required of citizens in a thriving democracy. That this is an excellent suggestion no one would dispute. The first recommendation associated with Goal 3 was to promote foreign language education, to enable Americans to enlarge their cultural perspective. Again this is an excellent and welcome suggestion.

But here we have exhausted the list of the high points. The remainder of the report is filled with such dubious assumptions and faulty reasoning that even the hungriest humanities teacher, clutching at the report as a sign of hope against the increasingly narrow emphasis on science and technology in our education system, ought to be circumspect in heralding it as a great stride forward.

The Cart Before the Horse

The fundamental problem with the report, as I see it, is that it has reversed the traditional ends and means of the humanities (and, by extension, of the social sciences, to the extent that both have similar goals; I shall herein, however, mainly address myself to the humanities). The principle feature of the humanities is, almost by definition (that is, to the extent that ‘humanities’ mean the same thing as ‘Humanism’), that, in the best meaning of the phrase, the proper concern of man is man: that what we are really aiming at is human happiness and self-actualization; to empower man, to achieve the telos latent in his potentialities; to obtain what the ancients simply called the good life or beata vita. Now as to what constitutes this good life, of course, there is some disagreement; but there is also considerable agreement: we seek a life where human beings are healthy, have ample leisure time, opportunities for education, where they enjoy the arts, study and practice philosophy, and so on.

In the modern era it has become an unquestioned assumption that we should also advance technology at a brisk pace, and, partly as a means of doing this, that our commercial economies should be robust and growing as well. I tend to agree with this view, personally. Yet where I evidently part company with the authors of the AAAS report is that I see the latter of these two goals – technological and economic advancement – as subordinate to the primary goal of obtaining ‘the good life’. That is, to the extent that technological and economic growth gives us anti-malaria vaccines, freedom from hunger, computers, solar energy, digital classical music, open access online libraries, and so on, it is good. But when it means pollution, constant stress and anxiety, urban sprawl, perpetual war, corporation-run government, and a long commute to and from a mindless job pushing papers in a cubicle all day long merely to earn enough money to continue on the treadmill, then I think we have ample grounds for doubt, and to consider forging for ourselves a new vision of society. May we put wage slavery and mass consumerism on the table as negotiable, and consider organizing our society for the 21st century and beyond in some more favorable way?

The gaping hole in the report’s logic is that it presents, apparently without the authors’ having any cognizance of its absurdity, if not outright danger, that we should improve the humanities in order to improve our economies, when it ought to be the other way around. We are told that we should increase spending on the humanities and social sciences so that we may have “an adaptable and creative workforce”, and that, presumably to counter the economic threat posed by China or other developing nations, we need “a new ‘National Competitiveness Act'”, which is somehow supposed to be “like the original National Defense Education Act.”

That the authors would so deftly and unhesitatingly leap from “competitiveness” to “national defense” – and all in a report addressing the humanities and social sciences – ought by itself to alert us that something is not quite right. But lest there be any doubt, we need only consult the flag-draped cover to learn that we need the humanities and social sciences “for a vibrant, competitive, and secure nation.” [underscore added] There you have it: we need the humanities and social sciences for national security. Do your duty: Uncle Sam wants you to read Shakespeare! How else can we defeat the infidel third-world hordes greedily eyeing our huge piece of the global economic pie? The world economy belongs to America, and our ticket to continued hegemony is the Humanities!

On page 59 we are treated to a photo of a US soldier in full combat gear who looks like he might be instructing his comrades in the finer nuances of Afghan culture and how to persuade the locals to rat-out the Taliban. Yes, definitely expand our Mid-Asian Studies programs, so that our future military occupations might be more effective than they have been of late. Or maybe the idea is that by studying foreign cultures better, we’ll have more success in instigating, funding, and arming rebel insurgencies to displace regimes antithetical to our economic interests.

Materialism vs. Idealism

The tragedy of the report is that it seeks to promote the humanities without the vaguest idea of what Humanism is, or even an awareness that this is something people have made some serious effort to define over previous decades, centuries, and millennia. Now, to my mind – and I’m scarcely alone in this opinion – Humanism of necessity implies some sort of transcendent orientation. What makes human beings distinct and unique in the order of creation is that they are not only material, biological organisms, but contain something divine. This is the classical, the Renaissance, and the religious basis of Humanism. Not all humanists would agree, and I respect that. But at least could we agree to acknowledge that the effort to define Humanism is something that ought to occupy our attention? Is it asking too much to cite at least a single book, report, or article on the topic in a report that presents itself to be expert and authoritative? I would rather see Matthew Arnold, Cardinal Newman, or Plato in the bibliography than Emmy-Lou Harris, George Lucas, and John Lithgow in the panel of experts whom the report consulted.

We are told, for example, nothing of the 1984 National Endowment for the Humanities report (‘To Reclaim a Legacy: A Report on the Humanities in Higher Education’) authored by William J. Bennett. That report, while not as lavishly produced as the present one, nonetheless had a little more intellectual heft, at least insofar as it connected itself with traditional principles of Humanism, classics, and liberal education. A natural question to ask is whether the effort to renew the humanities initiated by the 1984 report worked. Apparently not too well, or we wouldn’t need a new initiative. But unless we look at that earlier report and examine what happened since, how can we understand what went wrong (or right), or know whether the present plan will fare better?

Despite a bit of lip service paid to ethics and morals, the values of the report are materialistic and mercenary. Small wonder, then, that the solution proposed is to throw more money at the problem. We’ll buy back the heart and soul of America. But did it ever occur to the authors that we already have the raw materials for a new cultural renaissance, and that what is wrong is not lack of money but wrong values? Instead of throwing money at the problem, couldn’t we simply persuade people to start reading Great Books? And without a prior shift in fundamental values, how can simply funding interdisciplinary research centers or developing a “Culture Corps” (yes, they seriously proposed that) accomplish anything?

A more minor point, but one nevertheless worth making, is how suavely the report dismisses the tuition and student loan crisis in the country today. Not a crisis, we’re informed; more like an inconvenience. The point the authors miss is the effect that placing college students deeply in debt has on their educational goals. One’s not likely to pay off a $75,000 student loan any time soon by majoring in American literature or ancient history. And the debt-burdened graduate isn’t likely to wander around Europe or Asia for the sheer pleasure of broadening ones cultural horizons. Better to major in accounting and hope to land a job with Bank of America.

Ironically, the report succeeds, after a fashion, in its failure. Its deficiencies themselves speak volumes about the decline of the humanities in the American university system. The report is the product of a higher education industry that has systemically neglected liberal education for at least 100 years. That we need to address this problem is abundantly clear. But to give more money to an education system not wise enough to understand what the humanities are and mean scarcely seems like the answer.

The report is all window dressing and the only real message is “give us money.” But the heart is not bought.

President Woodrow Wilson

President Woodrow Wilson

The Immortal I

The Immortal I

You must be logged in to post a comment.