Archive for the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ Category

End Diploma Discrimination!

Wherever I go in California these days I meet young people who either can’t afford to attend college, so they don’t, or else are going to college and taking out huge student loans. (I don’t know which group I feel more sorry for, though I think the first group are smarter.)

The thing is, none of this is necessary. The problem, of course, is the unrealistic and outrageously high tuitions at colleges and universities today. And while I’m scarcely a knee-jerk ‘free market solves all’ libertarian, in this case I think the principle applies. The reason tuitions are so high is because we have a closed system, a monopoly of players in collusion who control higher education. The racket works like this:

- Universities convince people that they need a diploma to get a job.

- Employers collude with universities, so that they do in fact require diplomas.

- Further add the requirement that the diploma must be granted by an accredited university.

- Control which colleges and universities get accredited and which don’t, thereby limiting competition. In particular, make the accreditation process so expensive that small independent colleges are excluded.

The net result is that the service (education) becomes virtually mandatory, but only members of the monopoly can supply the service. Consequently the members of the monopoly can charge (or extort) unrealistically high tuitions and get away with it.

So there are two related problems that go into making higher education a monopoly: accreditation, and the use of diplomas. My proposal is that we should seriously consider eliminating both. By eliminating accreditation we would open the marketplace to free competition, the result being lower prices. By eliminating diplomas, at least at the undergraduate level, we would teach people because they want to learn, not because they want a piece of paper.

What is the rational basis for accreditation? One can see why, perhaps, we should require physicians to be licensed — we don’t want quacks endangering the lives of unsuspecting patients. But do students need to be protected from ‘incompetent’ colleges? Can’t we let students themselves decide which colleges are supplying adequate service?

Consider the power of consumer choice in other areas. Does a hamburger chain need to be accredited, or can it just sell hamburgers, competing with other chains, succeeding if it satisfies customers and failing if it doesn’t? Do you check to see where your car mechanic is trained before doing business? Or do you choose based on demonstrated skill and reasonable price? If you can make your own choice of mechanics, restaurants, and movies, why are you deemed incapable of discriminating between excellent and lousy colleges? Why do you need an accreditation organization to do this for you?

Let’s look at another reason people claim to need accreditation: to control admission to professional and graduate schools. So accredited doctoral programs require bachelor’s or master’s degrees from accredited universities so they can turn out PhD’s qualified to teach at accredited universities. It is egregiously self-serving.

I hate to disappoint my fellow academicians, but I have a little confession to make. I went through a fully accredited PhD program. But the truth is that I learned almost nothing in my classes. There were a few good professors, but more often than not they were pompous bores. What I did learn I mainly learned by checking statistics books out of the library and reading in my own time. I taught myself Fortran, developed skill as a programmer, and wrote statistics and simulation programs. That was how I got my education. And I could have done just as well at an unaccredited university — or for that matter, if supplied only with a library pass and computer account.

It surprises me that people aren’t challenging employer diploma discrimination in court. It is a flagrant injustice, if not a clear-cut abuse of civil rights. Take two identical twins. Send one to an accredited university for four years, give the other a computer and internet access. Let them both read the same books and articles. Let one attend in-person lectures, let the other buy lectures from The Teaching Company. After four years you will likely find two equally well educated people. Then have them both send job applications to the same company. The non-degreed twin won’t even be granted an interview; his or her resume won’t be read or sent out of the HR department. Does anybody seriously believe that is legal?

It amazes me that so much interest and energy gather around an issue like gay marriage equity, while everybody sits silently and tolerates diploma discrimination, which is arguably much more serious, because it amounts to rich vs. poor discrimination, unmitigated elitism, and exploitation.

The Prisoners’ Dilemma and Third-Party Voting

[ Related: Responding to the ‘Voting for Jill Stein Merely Elects Trump’ Fallacy ]

Does game theory explain why Americans don’t vote for third-party candidates?

Previous posts here have considered the tactics by which the Republican and Democratic parties collude to maintain a two-party hegemony in America politics. Lately it’s occurred to me that this problem can be understood as a special case of what game theorists call the prisoner’s dilemma (Rapoport, 1965). Prisoner’s dilemma (PD), as we shall see, is a classic example of how two decision-making agents, both seemingly seeking to maximize self-interest, systematically make harmful or suboptimal choices. In the present case, the issue is that even though American voters would be better off voting for third-party candidates, there are structural reasons why they do not do so. Looking at this problem in terms of PD can help identify the structural issues at work and suggest possible routes out of our present political impasse.

A few other people (e.g., John Sallet, and EvilRedScandi) have looked at PD as a way to understand current political dynamics, but their concerns are somewhat different than the present one, which is how Republican and Democrat voters today are jointly in a prisoners’ dilemma.

First we’ll describe the basic PD paradigm. Then we’ll show how this applies to reluctance to vote for third-party candidates. Last and perhaps most importantly we’ll consider practical steps for reform that the model suggests.

Prisoner’s Dilemma

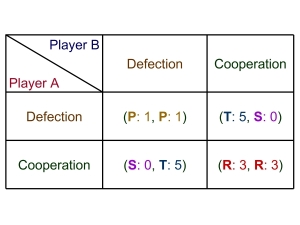

PD is a game theory paradigm that demonstrates how two decision-makers paradoxically fail to maximize either individual or joint interests. Specifically, though their best strategy would be cooperation, they systematically choose non-cooperation. The basic model can be understood with the following example:

Early one Saturday you and a college friend go hunting for ‘magic mushrooms’ in Farmer Brown’s cow pasture. Farmer Brown sees you and calls police Chief Wiggum, who arrives promptly, arrests you and your friend, and hauls you both to the police station. There Wiggum places you in a room by yourself and proposes the following deal (he also tells you he will propose an identical deal to your friend). The terms are as follows. He asks you to sign a confession admitting that you and your friend were gathering the mushrooms with the intent of selling them (i.e., drug-dealing). Then:

- If you confess, and your friend doesn’t confess, he will go to jail for 10 years, and you will get a 90-day sentence.

- Conversely, if your friend confesses and you don’t, he will get a 90-day sentence, and you will get a 10-year sentence.

- If you confess and your friend also confesses, you’ll both be given 5-year sentences.

- If neither of you confess, Wiggum explains that he can still charge you and your friend with trespassing and put you both in jail for 30 days.

We can represent the dilemma with reference to a payoff matrix that considers each possible combination of choices and their consequences. You and your friend must each choose between cooperation with each other (not confessing), or defecting (confessing). The days and years indicate the amount of jail time associated with each case.

Table 1. Classic Prisoner’s Dilemma

| Friend doesn’t confess |

Friend confesses |

|

| You don’t confess |

you: 30 days friend: 30 days |

you: 10 yrs. friend: 90 days |

| You confess |

you: 90 days friend: 10 yrs. |

you: 5 yrs. friend: 5 yrs. |

The best strategy here is clearly 4 — for neither of you to confess. This is optimal both from the standpoint of selfish and altruistic motivation. The paradox is that people in this situation predictably end up in scenario 3 (confess/confess). So both of you go to jail for 5 years, when you both could have gotten off with 30-day sentences.

The pernicious aspect of PD is that this happens almost inevitably. Why? It has to do with what game theorists call the principle of dominance. Relative to Table 1 that means that whatever your friend’s choice is – that is, whether you’re looking at column 2 or column 3 of the table – your self-interest is maximized by defecting; thus, the strategy of defection is said to dominate that of cooperation. And similarly for your friend. Therefore, paradoxically, if maximizing self-interest is the only consideration, both of you will defect, and neither will maximize self-interest.

A detail is that although we’ve explained the dilemma in terms of various punishments, the crafty allocation of positive incentives, alone or in combination with negative incentives, can have the same effect. So, for example, Chief Wiggum can sweeten the deal with a bribe. He could offer to give you or your friend say $100 if the one defects and the other doesn’t.

An important extension of the model is iterative PD, where two agents are presented with the dilemma multiple times. Many researchers have studied iterative PD experimentally, e.g., seating two volunteers at computer terminals and repeatedly asking them to cooperate or defect, awarding payoffs (e.g., M&Ms, poker chips, money) each round. A variety of player strategies are seen. Sometimes players converge on cooperation, sometimes not. One not uncommon outcome is a tit-for-tat dynamic, in which players cooperate for a while, but if one defects, the other player retaliates by defecting in the next round, and this may go back and forth many times. In any case, the iterative PD corresponds to our national elections, which occur at regular two or four-year intervals.

Third-Party Voting

Let’s now see how this applies to third-party voting. Our initial premise is that, while one might suppose that the Republican and Democratic parties are competitors, they’re really a duopoly. Both serve the same ruling powers. They thus represent a single agent, which we might call Wall Street, the System, the Establishment, etc. Whatever we call it, it corresponds to the role of the interrogator in our PD.

The role of you and your friend correspond to a given Republican and a given Democrat voter, or perhaps groups or Republican and Democrat voters.

The essence of the third-party voting PD is that it is in the best interests of both Republican and Democrat voters, individually and jointly, to replace or radically reform the present two-party duopoly. Unless or until the two big parties nominate better candidates, the logical solution is for large numbers of citizens to vote for third-party candidates. The paradox is that voters are not doing this, but are choosing to keep the aversive two-party system in power.

This happens, we propose, because of how the ruling powers structure perceived payoffs, both by their selection of candidates and by party platforms.

Here PD makes an unexpected prediction. Common sense might suggest that to win office, a party should nominate candidates who (1) appeal to its own voters, but also (2) are either somewhat attractive, but in any case not terribly offensive to voters in the opposite party. That way some voters in the opposite camp might switch votes, or perhaps may feel it’s not important to vote at all. In either case, the party’s chances of winning are improved.

However if we grant that the Republican and Democrat parties are controlled by Wall Street and colluding with each other, PD implies that they will follow an opposite strategy, namely to nominate candidates who are frightening or even detested by voters of the opposite party. In such a fear- or anger-driven campaign, fewer voters will break ranks, believing that the opposite party must be prevented from winning at all costs. All votes will be cast for the two big parties – precisely as Wall Street wants.

To further encourage voters not to break ranks, each party also offers positive incentives in the form of platforms and campaign promises: for example universal health care or gay marriage by the Democratic party, or tougher immigration laws and Second Amendment protection but the Republican party. But, again, PD would predict that parties would be especially keen to offer incentives that are hated by voters of the opposite party.

Table 2 presents the PD that Republican and Democrat voters faced in the 2008 presidential election. (Cooperation here means voting for a third-party candidate, and defection means voting for the nominee of ones own party.)

Table 2. 2008 Presidential Election as Prisoners’ Dilemma

| Dem. voter cooperates | Dem. voter defects | |

| Rep. voter cooperates | Election a toss-up, Two-party hegemony rejected |

Obama/Biden win, ‘Obamacare’ |

| Rep. voter defects | McCain/Palin win, More guns |

Election a toss-up, Two-party hegemony affirmed |

If we suppose that both main parties represent Wall Street and are ultimately inimical to the interests of the public, the best strategy for Republican and Democrat voters is to vote for some third-party candidate. That won’t change the power structure immediately, but over the course of two or three elections sufficient momentum may build to make a third-party candidate competitive. If nothing else, this may force the two big parties to become more responsive to citizens.

However what is happening instead is that voters are afraid to do this. So, to consider the 2012 presidential election, despite the disillusionment of many Democrats with Obama, and the unattractiveness of Mitt Romney to many Republicans, the combined votes received by all third-party candidates amounted to less than 2% of the total.

Practical Implications

Viewing third-party voting as a PD suggests specific strategies for extricating American voters from their current predicament. Several, but not all, of these strategies relate to improving the perception of payoffs so that cooperation, i.e., voting for third-party candidates, is more appealing. Specific strategies include the following:

Accurately perceive costs of non-cooperation. The ultimate problem is that Democrat and Republican voters are not accurately considering the costs of maintaining the two-party hegemony and the benefits of electing third-party candidates. If the true costs and benefits were salient in our minds, we would more eagerly vote against the abusive and arrogant Republican-Democratic party establishment.

Our social problems today are many and serious: the economy is moribund, rates of unemployment and foreclosures intolerable, college tuitions insanely high, the environment is being destroyed, civil liberties disappearing; the country is engaged in perpetual war, and a spirit of divisiveness and antagonism dominate.

Less often considered, but perhaps even more important are the ‘opportunity costs’, i.e., besides these negative things, what positive things are we missing out on because of our dysfunctional and aversive government? Objectively considered, America has sufficient natural and human resources to construct a veritable utopia; we could eliminate poverty, grant free higher education and health-care for all; we have enough land to let everyone live in their own houses on their own property in environmentally friendly and attractive communities. Indeed, the blessings of nature generally, and in our country particularly, are so great that it seems we must make a concerted effort to avoid constructing such a prosperous and congenial society. We need a clearer vision of how good life could be were we only to stop punishing ourselves with the present inimical political system.

How can we gain this vision? Surely we still have individuals with the imagination and skills to lead. We must develop and empower these natural leaders and intellectuals. One obvious means of doing this is to reform our higher education system, which, by now neglecting liberal studies and humanities in favor of teaching technical and money-making skills, is discouraging the emergence of a more utopian vision of society.

We can also promote voter cooperation by applying more skepticism and critical thinking to the promises of Republican and Democrat candidates. For example, a Democrat candidate may well promise universal health care, which sounds very attractive at face value, but ought to raise many obvious questions about its feasibility or unintended side-effects. Would government-run health-care produce an unwieldy and inefficient bureaucracy? Would the government give too much power to pharmaceutical companies? Are there cheaper and better alternatives, such as a greater emphasis on preventive medicine and healthy living? Subjected to greater scrutiny, the promises of the two parties can be seen as empty, or in any case far less attractive than the kind of society we could obtain by having a government based on citizens’, not corporations’ interests.

Long-term perspective. Clearly another way to acquire more a accurate perception of the payoff structure, so as to better see the benefits of cooperation by voting for third-party candidates, is to adopt a long-term perspective. A bias favoring immediate wishes over long-term welfare is, of course, a fundamental problem of human nature. But the problem is especially great in politics, where demagogues and news media specialize in appealing to voters’ short-term interests. In any given election, the short term benefits promised by Republican and Democrat candidates may seem attractive to their respective constituencies, but over the course of 10 or 20 years alternations of policy and failure to pursue any consistent course is disastrous.

Collectivize utilities. By collectivizing utilities I mean for individual citizens to recognize their own best interests and those of their fellow Americans are intimately connected. We are a highly interdependent society. Ultimately, social injustice or unfair distribution of wealth harms everyone. If one segment of the population is oppressed or excluded, or their views ignored, then at the very least their contribution to society will be lessened, and this hurts everyone. Moreover, eventually an oppressed or underserved group will gather sufficient energy to redress the wrong by political action. Whatever is at the basis of the ideological split between Republicans and Democrats, the current political dynamics operate as a negative feedback system: as one group gains successive victories, opposing pressure builds until a reversal occurs. Thus victories are often short-lived, policies flip-flop, and no sustained course is pursued.

Consider higher-order utilities. The utility calculus of voters is such that typically only material values – jobs, benefits, taxes, etc. – are considered. Americans have bought lock, stock and barrel the political lie that “it’s the economy, stupid”, i.e., that all success and value of our society is measured by the GNP. This does not reflect the true value structure of human beings. We are not merely material creatures, but moral and spiritual beings as well. It is an undeniable fact that people feel good and experience more happiness and satisfaction when they practice generosity, altruism, benevolence, charity, and justice. Add to this that no amount of material benefits can outweigh the disadvantages of citizens being constantly at each others’ throats. In an authentic utility calculus, higher-order utilities have to be considered; and if they are, the payoff much more clearly favors cooperation among voters and rejection of the two-party hegemony.

Third-party platforms and rhetoric. Third parties must confront Americans with the price being paid for two-party totalitarianism and emphasize that a better future is obtainable.

Voter pacts. Beyond changing perceptions of payoffs, there are active steps that people in a prisoners’ dilemma can do to win the game. Perhaps the most obvious is for the two players to anticipate the dilemma and form a pact beforehand. For example, with regards to Table 1, you and your friend could agree beforehand, “If we’re caught, we both promise to assert our innocence.” This solution is enhanced by establishing or improving trust, affection, and bonds of unity between the two players.

In theory, individual Republican and Democrat voters could pair up with a member of the opposite party and agree to vote for third-party candidates. A website might be set up for this purpose. While this is sensible and ethical, I believe that at least certain forms of voting pacts have been ruled illegal, and one website dedicated to this was forced to close. Nevertheless this principle could doubtless be applied in ways that are unambiguously legal, or at least such that contrary prohibitions would be unenforceable.

Bargains could also be made at the level of institutional endorsements. For example, two newspapers, one liberal and one conservative, could make a pact to endorse third-party candidates.

Opting out. Finally, citizens might opt out of the dilemma in various ways. I would personally not advocate failure to vote as a means for this, although some suggest it. Protests, demonstrations, or even strikes might be used to pressure the Republican and Democratic parties to reform their platforms and supply better candidates. Another possibility is to hold alternative elections run by the citizens themselves with candidates of their own choosing. Such elections would have no legal status, but they would have symbolic value, would permit realistic debates about policy, and encourage trust and camaraderie amongst citizens.

These are only representative suggestions. How feasible or effective any of them would be remains to be seen. The main point here has been to suggest that PD is an appropriate paradigm for looking at the current two-party stranglehold on American society and understanding how to encourage third-party voting. I would like to encourage others, including social scientists, to consider this topic more, as I believe the model is apt and probably contains more theoretical and practical implications than have been considered here.

Post-script

Writing this article helped me to see the more fundamental problem: American society generally is an n-way prisoners’ dilemma. When people view society as merely a ‘dog-eat-dog’ competition, they ‘rationally’ choose to maximize self(ish)-interest. But selfishness only pays off when other people act unselfishly. When everybody acts selfishly, everyone loses; thinking you’ll win by acting selfishly is an illusion.

Each person is better off when everybody cooperates. This is more than an ethical maxim, it’s demonstrated by game theory.

This problem (whether to vote for a third-party candidate, or a less preferred candidate that is more likely to win) is an instance of a more general class of social dilemmas. As such it is not only related to the prisoners’ dilemma but also the tragedy of the commons. Several other forms of insincere voting that constitute social dilemmas. For all such dilemmas, the long-term optimal strategy is cooperation, viz. for each agent to choose so as to maximize long-term collective, not immediate personal utility.

Further Reading

Rapoport, Anatol. Prisoner’s Dilemma: A Study in Conflict and Cooperation. University of Michigan, 1965.

Uebersax, John. The Lions and the Tigers (A Political Parties Fable).

Uebersax, John. Third-Party Voting and Kant’s Categorical Imperative.

Uebersax, John. Voting as Constructive Idealism: Why Principles Do Matter More than Expediency.

Uebersax, John. Why Vote Third-Party?

Fiat Lucrum: Berkeley Faculty vs. California Citizens on Online Courses

California State Senator Darrell Steinberg is co-sponsoring SB 520, titled “California Virtual Campus.” The Senate Bill would potentially enable California students to receive credit at public universities and colleges (UCs, CSUs, and CCCs) for courses taken online from any source. This would presumably stimulate competition, lower course costs, and make higher education available to more Californians.

Predictably, there is resistance from faculty associations. The Berkeley Faculty Association, for example, is circulating a petition to oppose SB 520. The petition states that SB 520 “will lower academic standards (particularly in key skills such as writing, math, and basic analysis), augment the educational divide along socio-economic lines, and diminish the ability for underrepresented minorities to excel in higher education.”

This, of course, is all nonsense. Nearer the truth is that the Berkeley Faculty Association wants to protect faculty jobs. It is sad indeed when they place their own job security ahead of sensible efforts to make higher education affordable and accessible to more Californians.

That said, anything the State Government touches will be tainted by money. No doubt many private online universities (e.g., Univer$ity of Phoenix) will jump at the new chance to make money. Whether online universities are actively lobbying State Senators is anybody’s guess (but what do you think?).

What we ought to do is to simply eliminate expensive and needless accreditation requirements for undergraduate colleges, whether brick-and-mortar or virtual. Consumers and market competition would then assure the highest quality courses for the lowest price. We should similarly eliminate four-year degrees, which are meaningless. People should take classes for the purpose of learning, not to get a degree. If undergraduate education were completely de-regulated, everybody – minorities included – would follow their natural inclinations to educate themselves, and select high-quality vendors. A world-class college lecture series would cost no more than to rent a Blu-Ray movie.

James Freeman Clarke — Self-Culture by Reading and Books

ONE of the many hidden gems in New England Transcendentalist literature. This insightful essay by James Freeman Clarke (1810–1888) is as valuable today as ever. (Source: James Freeman Clarke, Self-Culture Physical, Intellectual, Moral And Spiritual. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1908 [orig. ed. 1880]; ch. 15, pp. 307–324.)*

space

Culture By Reading And Books

space

THE subject of this chapter is “Reading as a Means of Culture.”

The “Publisher’s Circular” gives the statistics of the books issued each year from the press in England. The annual number of titles, one year with another, is about five thousand. About two-thirds of these are new books; the others are reprints. Last year there were 737 theological books, 529 educational works, 522 juvenile books, and 854 works of fiction. I have not at hand the statistics of books for the United States, but it must compare favorably with that of England, as a larger proportion of our population are able to read than in that country. The number of copies of newspapers printed and circulated every year in the United States is enormous, — I was about to say frightful. The annual circulation is fifteen hundred millions of copies, which would give about forty copies every year to every man, woman, and child in the United States.

These statistics show how much time is occupied by the people in reading. And it is a valuable education, so far as it goes. Poor as much is that is printed, it is better than the common talk. The average newspaper is higher than the average conversation. The newspaper does not swear, does not use coarse and gross language; it is often weak, but does not talk pure nonsense. It is trying to say something, and it has to seem to be aiming at something honest, true, and generous. The newspapers give a vast amount of information in regard to the affairs of mankind. The nation which reads newspapers is able to sympathize with the people of other countries; men’s hearts are enlarged, and they are helped to love their fellow-men. Without newspapers, we should never have felt sympathy with Greece in her revolution, with Poland in its misfortunes, with Italy in its independence and unity, with France in her great disasters and subsequent recovery. Without the newspapers, we should not have sent food to starving Ireland in its years of famine, for we should, as a people, have known nothing about it. The newspapers create a common feeling and a common opinion through the whole land, and a sympathy with the people of other lands. So they help the cause of humanity and of social progress.

But with all this good done by reading newspapers, there is one particular evil. It produces that state of mind which the Book of Acts ascribed to the Athenians: “The Athenians and strangers at Athens passed all their time,” so we are told in the Acts, “in seeing and hearing some new thing.” What they wanted was not the new, but the novel. They wished for novel sensations, perpetual change. Therefore, neither St. Paul – nor Socrates four centuries earlier – had much success teaching the Athenians anything really new. There was no depth in that soil.

Now, today the newspaper creates and feeds the appetite for news. When we read it, it is not to find what is true, what is important, what we must consider and reflect upon, what we must carry away and remember, but what is new. When any very curious or important event occurs, the newspaper, in narrating it, often gives, as its only comment and reflection, this phrase, “What next?” That is often the motto of the newspaper and the newspaper reader, “What next?” The only reflection and moral derived from learning a great fact is simply this, “Now let us hear of another.” The whole world rushes to the newspaper every morning to find out what has happened since yesterday; and the moment it finds what has happened, it cares no more about it. We think no more of yesterday’s newspaper than of yesterday’s dinner. We forget both as soon as possible. This is a mental dissipation which takes away mental earnestness, and destroys all hearty interest in truth. It also weakens the memory. The memory, like all other powers, is strengthened by exercise. We cultivate our memory by remembering. But if we read, not intending to remember what we read, but expecting to forget it, then we cultivate the habit of forgetting. I think that the effect of reading newspapers, in the way we read them, must be to weaken steadily and permanently, the memory of the nation. Every generation will be born with a worse memory than that which preceded it. The proper way to cure this evil would be to select every day from the newspaper certain important facts to be carried in the mind, considered and thought about. These would be fixed in the memory. They should be made the subject of conversation with friends or in the family, and this would improve the memory, instead of destroying it.

In short, in reading, and in all that we read, our mind should be active, and not passive. Milton says:—

“Who reads

Incessantly, and to his reading brings not

A spirit and genius equal or superior,

Uncertain and unsettled still remains,

Deep versed in books and shallow in himself.”

And Lord Bacon tells us that “reading makes a full man, conference (or conversation) a ready man, and writing an exact man;” and that we should read, not to contradict and confute, nor to believe and take for granted, nor to find talk and discourse, but to weigh and consider. Montaigne, who had a passion for books, who never travelled without them, and called them the best viaticum for this journey of life, said that the principal use of reading, to him, was, that it roused his reason. It employed his judgment, not his memory. “Read much, not many things,” is good advice. There was an old saying, “He is a man of one book.” If one reads but one book, he may read that one book so well as to be a very hard man to encounter. But he is a happy person who enjoys his books, and to whom the day does not seem long enough for reading. For books are friends who never quarrel, never complain, are never false; who come from far ages and old lands to talk with us when we wish to hear them, and are silent when we are weary. Good books take us away from our small troubles and petty vexations into a serene atmosphere of thought, nobleness, truth. They are solace in sorrow, and companions in joy.

Knowledge of books, and a habit of careful reading, is a most important means of intellectual development. It gives mental breadth, poise, and authority. The man of great practical abilities, but unacquainted with the history or theory of a subject, is liable to make serious mistakes. He cannot be trusted. If he is conscious himself of his ignorance, he is timid; if not conscious, he is rash. It would be impossible for our members of Congress to commit so many blunders if they should pass an examination in political economy before taking their seats. To read two or three good books on any subject is equivalent to hearing it discussed by an assembly of wise, able, and impartial experts, who tell you all that can be known about it. You see the whole field, understand all that can be said on one side or the other, know what has been the result in practice of either course. The experience of the whole world, and of all past history, comes to your aid.

The moral influence also of good books is very great. They purify the taste, elevate the character, make low pleasures unattractive, and carry the soul up into a region of noble aims and generous purposes. All first-class books are eminently moral; and all immoral books are, so far, poor books. Homer, Shakspeare, Plato, Dante, are pure in their spirit, and elevate the character. No one can make a thorough study of such books as these without being a better man. Milton says, and says truly, that “our sage and serious poet, Spenser, is, I dare be known to think, a better teacher of temperance than John Duns Scotus or Thomas Aquinas.” Who can read the biography of Benjamin Franklin without learning to admire such a life of perpetual study, unfailing industry, large patriotism, temperance, good-humor, and general good-will? When we read the story of Washington we become sure that disinterested public service is a real thing. The charming allegory of the “Pilgrim’s Progress” teaches, in pictures too vivid to be ever forgotten, of the temptations and dangers we must encounter in any serious effort to save our soul.

Religious books are usually considered dull and uninteresting; but that they need not be so appears from the example of this book of Bunyan’s, and from the popularity of religious books far inferior in their quality. In fact, religious books stand at the summit of literature. First come the Sacred Scriptures of the race, —the books of books,—and, before all others, the Christian and Hebrew Bible, read by countless millions. Then come the Scriptures of the Hindus, the Persians, the Chinese, the Buddhists, also circulated by millions of copies during numerous centuries. Next come religious books of the second class, as the works of Homer, Hesiod, Aeschylus, Pindar; the great poems of Dante and Milton; and, after these, the lives of saints, the liturgies and hymns of the ages, the manuals of devotion, “The Imitation of Christ,” “Taylor’s Holy Living,” the works of Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, Wesley, Swedenborg, Channing. The vast circulation of such works testifies that there is nothing so interesting to the human heart as religion.

But “let him that readeth understand.” It used to be thought a great credit to a boy to “love his book,” to be fond of reading. But all depends on what we read and how we read. One may have a morbid love of reading. The habit of reading may become an evil. I have known persons who had acquired such a love for novel-reading that it was a real disease. They swallowed novel after novel as a rum-drinker swallows his glass of spirits. They lived on that excitement. They were passive recipients of these stories, and the more they read the weaker grew their minds. The result of this sort of reading is mental imbecility. Better, instead of it, to walk in the fields, to dig potatoes, or to talk with the first man you meet.

I do not mean to say that novel-reading is necessarily bad. It was formerly thought wrong to read novels at all; or, at least, wrong to read anything but the regular moral romance: the writings of Miss Edgeworth, Miss Burney, and the like. But novels in which the moral is too prominent are usually not so influential as those in which it comes, as in life, out of the incidents themselves. “The Vicar of Wakefield” has not any moral which compels your attention. “Don Quixote” has no obtrusive moral. But who can read the first and not sympathize with the good man, who, with all his ignorance of the world and its ways, commands our respect by his honorable purposes and his loyalty to truth and right. So, while we read “Don Quixote,” we smile at the folly of the good knight with the surface of our mind, and love and honor him in the depths of our heart, for the magnanimity and nobleness of his character. We smile at him, but respect him. Such books make us feel how much better is inward purity and uprightness than any mere knowledge of the world or outward success. That is their moral, and it is a great one. But it is nowhere stated in so many words.

The great merit of Walter Scott’s novels is their generous and pure sentiment. There is a strain of generosity, manliness, truth, which runs through them all. They nowhere take for granted meanness; they always take for granted justice and honor. Now this is the real, though subtle, influence which comes from novels, poems, plays. This indirect influence, this taking for granted, is the most influential of all. Some books take for granted that man is selfish and mean. Others take for granted that he is noble and true. Some assume that all men are led by selfishness, and all women by vanity. Such books are deeply immoral, no matter what good maxims are tacked to them. For our standard of right and wrong is usually that of the public opinion just around us, and the books we read create a part of that public opinion. Such works as those of Dickens have gone into public opinion, and have been the guides of the public conscience. They have made us all feel the duty of caring for such poor orphans as Smike; they have made us love the lowly; they have infused an aroma of generous feeling into the public mind. Catholics have their confessors, and those priests whom they call their directors, to whom they go to tell them what they ought to do. Such writers as Scott and Dickens are the directors of the public conscience. Well when they direct it aright.

Novels are good or bad, like other books. To ask whether we ought to read novels is like asking whether we ought to go into society. Choose your associates; choose your books. Do not read anything and everything because it is printed. Meanness, cynicism, cruelty, falsehood, get themselves printed. It is necessary that each one should examine for himself the character of what he reads, and find what effect it has on him.

Let him that readeth understand. “Weigh and consider.”

I return to the maxim to which I referred above, non multa, sed multum. Read much, but do not read many things. Select the great teachers of the race, the great masters, and read them. Read Bacon, Milton, Shakspeare, Dante, Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides, Schiller, Goethe, Lessing. Do not read about these authors in magazines, but read the authors themselves. He who has once carefully read Bacon’s “Advancement of Learning,” or Milton’s “Areopagitica,” or the “Phaedo” of Plato, has taken a step forward in thought and life. We read many criticisms on books; it were better to read the books themselves. Who, in visiting Niagara, instead of looking at the majestic cataract itself, would wish to see it reflected in a mirror in a camera obscura? Drink at the fountain, not from the stream. Read Pope, rather than Dr. Johnson’s account of him. Read Milton before you read Macaulay’s article on Milton. Read Goethe, and then Carlyle’s essay on Goethe. Literature tends too much to diluted and second-hand reading. Instead of great books, we read the reviews of books, then articles on the reviews, then criticisms on those articles, then essays on those criticisms.

It is an epoch in one’s life to read a great book for the first time. It is like going to Mont Blanc or to Niagara without the journey or the expense. When I was a boy I lived in the country, and had constructed for myself a reading-room amid the massive limbs of an old chestnut-tree. There I retired, and spent long mornings in reading the plays of Shakspeare, the “Paradise Lost,” the songs of Burns, the poems of Wordsworth or of Walter Scott. I immersed myself in them. The hours passed by, the sun sank lower toward his setting, the shadows moved on; entranced in my book, I read and noticed nothing. To read a good book thus is an event in one’s life.

I once spent a long day in reading the Book of Job in the translation of Noyes. I had never read it before from the beginning to the end. It was a day much to be remembered. I beg of you to take such books as these when you have time enough, and read them through; else you cannot know how great they are. Such books are not meant to be read as serials, or to be issued in monthly numbers. To read Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” take a long summer’s day. Go into the country, and sit in the woods alone. Read on and on, and give the whole day to it. Only so can you realize the majesty of that muse,—

“Sailing with supreme dominion

Through the azure depths of air,”

— the genius which paints in turn the sublime horrors of hell, the tender beauty of paradise,—

“The spirits and Intelligences fair

And angels waiting on the Almighty’s chair.”

In reading a book, you will notice that besides the thoughts, besides the visible moral, it has a soul, a leaven of character. The words of a book may be very moral, but the tone immoral. The words may be religious, but the tone sceptical. For the religion may be a mere smooth, cold crust over a deep running tendency to doubt; the morality may be exhortation to correct conduct coming out of a spirit which does not believe in right or wrong. That book, to me, is not moral which is stuffed with moral maxims, or in which good people end by getting rich and prosperous; but that which makes goodness seem both beautiful and possible; which makes it seem worth while to live, that we may live generously and nobly. That book to me is religious, not which exhorts us solemnly to become pious under penalty of going to hell if we are not, but in which love to God and man seem natural, easy, and beautiful.

A book may be religious without being Christian. The religious feeling which pours itself out in expressions of awe, reverence, fear, remorse, trust, is nearly the same in all lands, all times, and all religions. Something of it is to be found in Buddhism, in Mohammedanism, among the Hindus and the Chinese. But Christianity adds the element of faith in God as a living friend, close to us. The spirit of Christianity is the spirit of Jesus. When a book has not the spirit of Christ, it is none of his, though it may be full of religious notions, and may be popular enough to reach a hundred editions. The book which has in it the spirit of Christ is an apostle of Christianity, though it be a novel by Dickens, or a poem by Tennyson.

Biography, history, and travels give us more information than any other kind of works. They should be read together. One illustrates the other. And I think these are the books to read in classes. The best way of learning history is to have a class, in which a certain period of history shall be the subject of the lesson, and each member of the class read in a different book about that period. Then, when they come together, each has something to tell to the others, and something to learn from them. And, in like manner, it is well to form classes to read other works and pursue other studies, for so the stimulus of society and co-operation aids the solitary study which accompanies it.

I will close these remarks with a few rules to assist in reading to advantage.

1. Read what interests you. Interesting books are those which do us good. Unless a book interests us, we cannot fix our attention to it. Unless we attend to it, we do not understand it, or take it in. Then, we are wasting our time on a merely mechanical process, and are deceiving ourselves with a show devoid of substance.

The best books are the most interesting. Those which are clearest, most intelligible, best expressed, the logic of which is the most convincing; which are deepest, broadest, loftiest. Therefore, read the books on subjects which interest you, by the best writers on those subjects. And these are also interesting to that degree that, having once read them, you will never forget them.

The most interesting books, as regards their subjects, are well-written biographies and well-written books of travels. The one shows us human nature, the other the world and life. Therefore the undying charm of such works as “Plutarch’s Lives,” Xenophon’s “Memorabilia of Socrates,” Johnson’s “Lives of the Poets,” the biographical essays by Macaulay and Carlyle, and the like.

This rule of reading what is interesting is so important, that it is a good appendix to the rule to stop reading when we find we cannot fix our attention and are reading mechanically. For to read without attention is to form a habit of inattention. To read without interest, will tend to a loss of interest in all reading. To go through the mechanical form of reading when our mind is not in it, weakens the mental powers, and does not strengthen them.

Therefore, select the best and most interesting books to read.

2. Read actively, not passively. A person may be deeply interested in a sensational story, but it is often a purely passive interest. He does not think about what he is reading. The result is a momentary excitement, and after it is over he has received injury rather than good from it. He is less fit to think or to act than he was before.

We should always, in reading, exercise memory, judgment, and the faculties of comparison and reason. We should repeat in our own words the substance of what we read, take notes of it, converse about it, fix it in our memory, discuss it with others, and compare it with other books on the same subjects. This takes time; but it is far better to read a few books carefully and thoroughly, than many books superficially. Good books should be read again and again, and thought about, talked about, considered and re-considered. So, at last, what we read becomes our own.

3. Therefore, read with some system and method. Arrange circumstances so as to keep yourself up to your work. One method is for two persons to read the same book, and to meet together to talk about it. I read a large part of Goethe and Schiller and some other writers in this way, in company with Margaret Fuller, spending two or three evenings every week at her house, talking with her about what we had been reading. An extension of this method is to form a class to read on certain subjects; for example, a new book, a period of history, a country and people, a system of philosophy, a science, and then to meet and discuss together this common subject. Such a class might be formed in connection with every book-club. Where this cannot be done, a person might, at least, have a note-book, and write down the heads of what he reads, and his own thoughts about it. To these notes he would afterward refer with pleasure and advantage.

If a person, in the course of some years, should read in this way such writers as Shakspeare, Milton, Bacon, Locke, Gibbon, Wordsworth, and our best American writers, he would, by this method alone, acquire a good education and a large intellectual development. Any one important book read in this way would enlarge amazingly the sphere of one’s knowledge. I knew a gentleman who read thus “Carlyle’s History of the French Revolution;” looking up every event, person, and place referred to, and taking notes of all, and thus he became thoroughly versed in the whole history of modern Europe.

Let us be thankful for books. I sympathize with Charles Lamb, who said that he wished to ask a “grace before reading” more than a “grace before dinner.” Let us thank God for books. When I consider what some books have done for the world, and what they are doing, how they keep up our hope, awaken new courage and faith, soothe pain, give an ideal life to those whose homes are cold and hard, bind together distant ages and foreign lands, create new worlds of beauty, bring down truth from heaven, —I give eternal blessings for this gift, and pray that we may all use it aright, and abuse it never. Thank God for books, —

“Those stately arks, that from the deep

Garner the life for worlds to be;

And, with their glorious burden, sweep

Adown dark Time’s untravelled sea.”

~ * ~

* I have made made minor edits to the text for the benefit of modern readers — webmaster.

The Founding Fathers on Party Strife (Quotes)

George Washington

Let me … warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

The alternate triumphs of different parties … make the public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common counsels.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

The common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

[The spirit of party] serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

[The spirit of party] opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

All combinations and associations, under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities, are destructive of this fundamental principle, and of fatal tendency. They serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put, in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

However combinations or associations of the above description may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

The unity of government which constitutes you one people is … a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very liberty which you so highly prize. But … it is easy to foresee that, from different causes and from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; … this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

It is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual, and immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.

~ George Washington, Farewell Address, 19 September 1796.

![]()

John Adams

There is nothing which I dread so much as a division of the republic into two great parties, each arranged under its leader, and concerting measures in opposition to each other. This, in my humble apprehension, is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil under our Constitution.

~ John Adams, Letter to Jonathan Jackson, 2 October 1780. In: Charles Francis Adams (ed.), The Works of John Adams, Vol. 9, Boston, 1854. pp. 510-11.

Abuse of words has been the great instrument of sophistry and chicanery, of party, faction, and division of society.

~ John Adams, Letter to J. H. Tiffany, 31 March 1819. In: Charles Francis Adams (ed.), The Works of John Adams, Vol. 10, Boston, 1856. pp. 377-8.

![]()

Thomas Jefferson

The greatest good we can do our country is to heal its party divisions, and make them one people.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To John Dickinson, 23 July 1801

To render us again one people, acting as one nation, should be the object of every man really a patriot. I am satisfied it can be done, and I own that the day which should convince me of the contrary would be the bitterest of my life.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Thomas McKean, 24 July 1801

I have never thought that a difference in political, any more than in religious opinions, should disturb the friendly intercourse of society. There are so many other topics on which friends may converse and be happy, that it is wonderful they would select, of preference, the only one on which they cannot agree.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To David Campbell, 28 January 1810

I hope we shall once more see harmony restored among our citizens, and an entire oblivion of past feuds. Some of the leaders who have most committed themselves cannot come into this. But I hope the great body of our fellow citizens will do it. I will sacrifice everything but principle to procure it.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Samuel Adams, 29 March 1801

The spirit of 1776 is not dead. It has only been slumbering. The body of the American people is substantially republican. But their virtuous feelings have been played on by some fact with more fiction; they have been the dupes of artful manoeuvres, and made for a moment to be willing instruments in forging chains for themselves.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Thomas Lomax, 12 March 1799

Difference of opinion leads to enquiry, and enquiry to truth.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Peter H. Wendover (Draft), 13 March 1815

The public judgment will correct false reasonings and opinions, on a full hearing of all parties.

~ Thomas Jefferson, Second Inaugural Address, 4 March 1805

I may sometimes differ in opinion from some of my friends, from those whose views are as pure and sound as my own. I censure none, but do homage to every one’s right of opinion.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To William Duane, 28 March 1811

I see the necessity of sacrificing our opinions sometimes to the opinions of others for the sake of harmony.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Francis Eppes, 4 July 1790

I respect the right of free opinion too much to urge an uneasy pressure on them. Time and advancing science will ripen us all in its course, and reconcile all to wholesome and necessary changes.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Samuel Kercheval, 5 September 1824

If we do not learn to sacrifice small differences of opinion, we can never act together. Every man cannot have his way in all things. If his own opinion prevails at some times, he should acquiesce on seeing that of others preponderate at other times. Without this mutual disposition we are disjointed individuals but not a society.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To John Dickinson, 23 July 1801

To the principles of union I sacrifice all minor differences of opinion. These, like differences of face, are a law of our nature, and should be viewed with the same tolerance.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To William Duane, 25 July 1811

I never submitted the whole system of my opinions to the creed of any party of men whatever, in religion, in philosophy, in politics, or in anything else, where I was capable of thinking for myself. Such an addiction is the last degradation of a free and moral agent.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Francis Hopkinson, 13 March 1789

The happiness of society depends so much on preventing party spirit from infecting the common intercourse of life, that nothing should be spared to harmonize and amalgamate the two parties in social circles.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To William C. Claiborne, July 1801

You will soon find that so inveterate is the rancor of party spirit among us, that nothing ought to be credited but what we hear with our own ears. If you are less on your guard than we are here, at this moment, the designs of the mischief-makers will not fail to be accomplished, and brethren and friends will be made strangers and enemies to each other,

~ Thomas Jefferson, To James Monroe, March 1808

I deplore with you the putrid state into which our newspapers have passed, and the malignity, the vulgarity, and mendacious spirit of those who write for them. … This has in a great degree been produced by the violence and malignity of party spirit.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Walter Jones, January 1814

If we can once more get social intercourse restored to its pristine harmony, I shall believe we have not lived in vain.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Thomas Lomax, 25 February 1801

Let us, then, fellow-citizens, unite with one heart and one mind. Let us restore to social intercourse that harmony and affection without which liberty and even life itself are but dreary things.

~ Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, 4 March 1801

Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans, we are all federalists.

~ Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, 4 March 1801

It will be a great blessing to our country if we can once more restore harmony and social love among its citizens. I confess, as to myself, it is almost the first object of my heart, and one to which I would sacrifice everything but principle.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Elbridge Gerry, 29 March 1801

A difference in politics should never be permitted to enter into social intercourse, or to disturb its friendships, its charities or justice.

~ Thomas Jefferson, To Henry Lee, 10 August 1824

![]()

Alexander Hamilton

Nothing could be more ill-judged than that intolerant spirit which has, at all times, characterized political parties.

~ Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist #1, 27 October 1787.

We are attempting, by this Constitution, to abolish factions, and to unite all parties for the general welfare.

~ Alexander Hamilton, Debates in the Convention of the State of New York on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, Tuesday, 25 June 1788. In: Henry Cabot Lodge, ed., The Works of Alexander Hamilton (Federal Edition), Vol. 2, New York, 1904, p. 57.

![]()

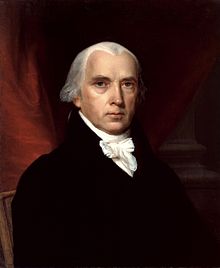

James Madison

A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have, in turn, divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good.

~ James Madison, The Federalist #10, 22 November 1787

So strong is this propensity of mankind to fall into mutual animosities, that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts.

~ James Madison, The Federalist #10, 22 November 1787

Hearken not to the unnatural voice which tells you that the people of America, knit together as they are by so many cords of affection, can no longer live together as members of the same family; can no longer continue the mutual guardians of their mutual happiness…. No, my countrymen, shut your ears against this unhallowed language. Shut your hearts against the poison which it conveys; the kindred blood which flows in the veins of American citizens, the mingled blood which they have shed in defense of their sacred rights, consecrate their Union, and excite horror at the idea of their becoming aliens, rivals, enemies.

~ James Madison, The Federalist #14, 30 November 1787

![]()

Benjamin Franklin

We must indeed hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Statement at the signing of the Declaration of Independence (4 July 1776).

Better is a little with content than much with contention.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

Clean your finger before pointing it at others.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

E’er you remark another’s sin, bid your own conscience look within.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

The proud hate pride — in others.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

Whate’er’s begun in anger ends in shame.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

Love your enemies, for they tell you your faults.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

Anger is never without a reason but seldom with a good one.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

The end of passion is the beginning of repentance.

~ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

“The small progress we have made after 4 or 5 weeks close attendance and continual reasonings with each other, our different sentiments on almost every question, several of the last producing as many noes as ayes, is methinks a melancholy proof of the imperfection of the human understanding. We indeed seem to feel our own want of political wisdom, since we have been running all about in search of it. We have gone back to ancient history for models of government, and examin’d the different forms of those republics, which, having been originally form’d with the seeds of their own dissolution, now no longer exist. And we have view’d modern states all ’round Europe, but find none of their constitutions suitable to our circumstances.

In this situation of this Assembly, groping, as it were, in the dark, to find political truth, and scarce able to distinguish it when presented to us, how has it happened, Sir, that we have not, hitherto once thought of humbly applying to the Father of Lights to illuminate our understandings? In the beginning of the contest with Britain, when we were sensible of danger, we had daily prayers in this room for the divine protection. Our prayers, Sir, were heard; — and they were graciously answered. All of us, who were engag’d in the struggle, must have observ’d frequent instances of a superintending Providence in our favour. To that kind Providence we owe this happy opportunity of consulting in peace on the means of establishing our future national felicity. And have we now forgotten that powerful Friend? or do we imagine we no longer need its assistance? I have lived, Sir, a long time; and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this Truth, That God governs in the affairs of men! — And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his aid? — We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings, that “except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it.” I firmly believe this; — and I also believe that without His concurring aid, we shall succeed in this political building no better than the builders of Babel: We shall be divided by our little partial local interests, our projects will be confounded and we ourselves shall become a reproach and a byword down to future Ages. And what is worse, Mankind may hereafter, from this unfortunate instance, despair of establishing government by human wisdom, and leave it to chance, war and conquest.

I therefore beg leave to move: That henceforth prayers, imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessing on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business; and that one or more of the clergy of this city be requested to officiate in that service.”

~ Benjamin Franklin, Motion for Prayers in the Constitutional Convention (28 June 1787). [Note: The Convention adjourned without voting on Franklin’s motion.]

“Steele, a Protestant in a dedication tells the Pope, that the only difference between our two Churches in their opinions of the certainty of their doctrine, is, the Romish Church is infallible, and the Church of England is never in the wrong. But tho’ many private persons think almost as highly of their own infallibility, as of that of their sect, few express it so naturally as a certain French lady, who in a little dispute with her sister, said, I don’t know how it happens, sister, but I meet with nobody but myself that’s always in the right.

In these sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution, with all its faults, if they are such; because I think a general government necessary for us, and there is no form of government but what may be a blessing to the people if well administered; and I believe farther that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic government, being incapable of any other. I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution: For when you assemble a number of men, to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an Assembly can a perfect production be expected? It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does and I think it will astonish our enemies, who are waiting with confidence to hear that our councils are confounded, like those of the builders of Babel, and that our States are on the point of separation, only to meet hereafter for the purpose of cutting one anothers throats. Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best…. I hope therefore for our own sakes, as a part of the people, and for the sake of our posterity, we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution, wherever our influence may extend, and turn our future thoughts and endeavours to the means of having it well administered.”

~ Benjamin Franklin, Speech at the Constitutional Convention at the Conclusion of Deliberations (17 September 1787)

The Immortal I

The Immortal I

You must be logged in to post a comment.