The Prisoners’ Dilemma and Third-Party Voting

[ Related: Responding to the ‘Voting for Jill Stein Merely Elects Trump’ Fallacy ]

Does game theory explain why Americans don’t vote for third-party candidates?

Previous posts here have considered the tactics by which the Republican and Democratic parties collude to maintain a two-party hegemony in America politics. Lately it’s occurred to me that this problem can be understood as a special case of what game theorists call the prisoner’s dilemma (Rapoport, 1965). Prisoner’s dilemma (PD), as we shall see, is a classic example of how two decision-making agents, both seemingly seeking to maximize self-interest, systematically make harmful or suboptimal choices. In the present case, the issue is that even though American voters would be better off voting for third-party candidates, there are structural reasons why they do not do so. Looking at this problem in terms of PD can help identify the structural issues at work and suggest possible routes out of our present political impasse.

A few other people (e.g., John Sallet, and EvilRedScandi) have looked at PD as a way to understand current political dynamics, but their concerns are somewhat different than the present one, which is how Republican and Democrat voters today are jointly in a prisoners’ dilemma.

First we’ll describe the basic PD paradigm. Then we’ll show how this applies to reluctance to vote for third-party candidates. Last and perhaps most importantly we’ll consider practical steps for reform that the model suggests.

Prisoner’s Dilemma

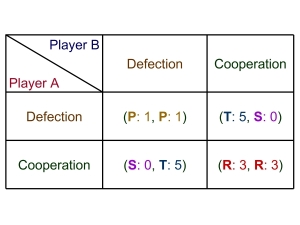

PD is a game theory paradigm that demonstrates how two decision-makers paradoxically fail to maximize either individual or joint interests. Specifically, though their best strategy would be cooperation, they systematically choose non-cooperation. The basic model can be understood with the following example:

Early one Saturday you and a college friend go hunting for ‘magic mushrooms’ in Farmer Brown’s cow pasture. Farmer Brown sees you and calls police Chief Wiggum, who arrives promptly, arrests you and your friend, and hauls you both to the police station. There Wiggum places you in a room by yourself and proposes the following deal (he also tells you he will propose an identical deal to your friend). The terms are as follows. He asks you to sign a confession admitting that you and your friend were gathering the mushrooms with the intent of selling them (i.e., drug-dealing). Then:

- If you confess, and your friend doesn’t confess, he will go to jail for 10 years, and you will get a 90-day sentence.

- Conversely, if your friend confesses and you don’t, he will get a 90-day sentence, and you will get a 10-year sentence.

- If you confess and your friend also confesses, you’ll both be given 5-year sentences.

- If neither of you confess, Wiggum explains that he can still charge you and your friend with trespassing and put you both in jail for 30 days.

We can represent the dilemma with reference to a payoff matrix that considers each possible combination of choices and their consequences. You and your friend must each choose between cooperation with each other (not confessing), or defecting (confessing). The days and years indicate the amount of jail time associated with each case.

Table 1. Classic Prisoner’s Dilemma

| Friend doesn’t confess |

Friend confesses |

|

| You don’t confess |

you: 30 days friend: 30 days |

you: 10 yrs. friend: 90 days |

| You confess |

you: 90 days friend: 10 yrs. |

you: 5 yrs. friend: 5 yrs. |

The best strategy here is clearly 4 — for neither of you to confess. This is optimal both from the standpoint of selfish and altruistic motivation. The paradox is that people in this situation predictably end up in scenario 3 (confess/confess). So both of you go to jail for 5 years, when you both could have gotten off with 30-day sentences.

The pernicious aspect of PD is that this happens almost inevitably. Why? It has to do with what game theorists call the principle of dominance. Relative to Table 1 that means that whatever your friend’s choice is – that is, whether you’re looking at column 2 or column 3 of the table – your self-interest is maximized by defecting; thus, the strategy of defection is said to dominate that of cooperation. And similarly for your friend. Therefore, paradoxically, if maximizing self-interest is the only consideration, both of you will defect, and neither will maximize self-interest.

A detail is that although we’ve explained the dilemma in terms of various punishments, the crafty allocation of positive incentives, alone or in combination with negative incentives, can have the same effect. So, for example, Chief Wiggum can sweeten the deal with a bribe. He could offer to give you or your friend say $100 if the one defects and the other doesn’t.

An important extension of the model is iterative PD, where two agents are presented with the dilemma multiple times. Many researchers have studied iterative PD experimentally, e.g., seating two volunteers at computer terminals and repeatedly asking them to cooperate or defect, awarding payoffs (e.g., M&Ms, poker chips, money) each round. A variety of player strategies are seen. Sometimes players converge on cooperation, sometimes not. One not uncommon outcome is a tit-for-tat dynamic, in which players cooperate for a while, but if one defects, the other player retaliates by defecting in the next round, and this may go back and forth many times. In any case, the iterative PD corresponds to our national elections, which occur at regular two or four-year intervals.

Third-Party Voting

Let’s now see how this applies to third-party voting. Our initial premise is that, while one might suppose that the Republican and Democratic parties are competitors, they’re really a duopoly. Both serve the same ruling powers. They thus represent a single agent, which we might call Wall Street, the System, the Establishment, etc. Whatever we call it, it corresponds to the role of the interrogator in our PD.

The role of you and your friend correspond to a given Republican and a given Democrat voter, or perhaps groups or Republican and Democrat voters.

The essence of the third-party voting PD is that it is in the best interests of both Republican and Democrat voters, individually and jointly, to replace or radically reform the present two-party duopoly. Unless or until the two big parties nominate better candidates, the logical solution is for large numbers of citizens to vote for third-party candidates. The paradox is that voters are not doing this, but are choosing to keep the aversive two-party system in power.

This happens, we propose, because of how the ruling powers structure perceived payoffs, both by their selection of candidates and by party platforms.

Here PD makes an unexpected prediction. Common sense might suggest that to win office, a party should nominate candidates who (1) appeal to its own voters, but also (2) are either somewhat attractive, but in any case not terribly offensive to voters in the opposite party. That way some voters in the opposite camp might switch votes, or perhaps may feel it’s not important to vote at all. In either case, the party’s chances of winning are improved.

However if we grant that the Republican and Democrat parties are controlled by Wall Street and colluding with each other, PD implies that they will follow an opposite strategy, namely to nominate candidates who are frightening or even detested by voters of the opposite party. In such a fear- or anger-driven campaign, fewer voters will break ranks, believing that the opposite party must be prevented from winning at all costs. All votes will be cast for the two big parties – precisely as Wall Street wants.

To further encourage voters not to break ranks, each party also offers positive incentives in the form of platforms and campaign promises: for example universal health care or gay marriage by the Democratic party, or tougher immigration laws and Second Amendment protection but the Republican party. But, again, PD would predict that parties would be especially keen to offer incentives that are hated by voters of the opposite party.

Table 2 presents the PD that Republican and Democrat voters faced in the 2008 presidential election. (Cooperation here means voting for a third-party candidate, and defection means voting for the nominee of ones own party.)

Table 2. 2008 Presidential Election as Prisoners’ Dilemma

| Dem. voter cooperates | Dem. voter defects | |

| Rep. voter cooperates | Election a toss-up, Two-party hegemony rejected |

Obama/Biden win, ‘Obamacare’ |

| Rep. voter defects | McCain/Palin win, More guns |

Election a toss-up, Two-party hegemony affirmed |

If we suppose that both main parties represent Wall Street and are ultimately inimical to the interests of the public, the best strategy for Republican and Democrat voters is to vote for some third-party candidate. That won’t change the power structure immediately, but over the course of two or three elections sufficient momentum may build to make a third-party candidate competitive. If nothing else, this may force the two big parties to become more responsive to citizens.

However what is happening instead is that voters are afraid to do this. So, to consider the 2012 presidential election, despite the disillusionment of many Democrats with Obama, and the unattractiveness of Mitt Romney to many Republicans, the combined votes received by all third-party candidates amounted to less than 2% of the total.

Practical Implications

Viewing third-party voting as a PD suggests specific strategies for extricating American voters from their current predicament. Several, but not all, of these strategies relate to improving the perception of payoffs so that cooperation, i.e., voting for third-party candidates, is more appealing. Specific strategies include the following:

Accurately perceive costs of non-cooperation. The ultimate problem is that Democrat and Republican voters are not accurately considering the costs of maintaining the two-party hegemony and the benefits of electing third-party candidates. If the true costs and benefits were salient in our minds, we would more eagerly vote against the abusive and arrogant Republican-Democratic party establishment.

Our social problems today are many and serious: the economy is moribund, rates of unemployment and foreclosures intolerable, college tuitions insanely high, the environment is being destroyed, civil liberties disappearing; the country is engaged in perpetual war, and a spirit of divisiveness and antagonism dominate.

Less often considered, but perhaps even more important are the ‘opportunity costs’, i.e., besides these negative things, what positive things are we missing out on because of our dysfunctional and aversive government? Objectively considered, America has sufficient natural and human resources to construct a veritable utopia; we could eliminate poverty, grant free higher education and health-care for all; we have enough land to let everyone live in their own houses on their own property in environmentally friendly and attractive communities. Indeed, the blessings of nature generally, and in our country particularly, are so great that it seems we must make a concerted effort to avoid constructing such a prosperous and congenial society. We need a clearer vision of how good life could be were we only to stop punishing ourselves with the present inimical political system.

How can we gain this vision? Surely we still have individuals with the imagination and skills to lead. We must develop and empower these natural leaders and intellectuals. One obvious means of doing this is to reform our higher education system, which, by now neglecting liberal studies and humanities in favor of teaching technical and money-making skills, is discouraging the emergence of a more utopian vision of society.

We can also promote voter cooperation by applying more skepticism and critical thinking to the promises of Republican and Democrat candidates. For example, a Democrat candidate may well promise universal health care, which sounds very attractive at face value, but ought to raise many obvious questions about its feasibility or unintended side-effects. Would government-run health-care produce an unwieldy and inefficient bureaucracy? Would the government give too much power to pharmaceutical companies? Are there cheaper and better alternatives, such as a greater emphasis on preventive medicine and healthy living? Subjected to greater scrutiny, the promises of the two parties can be seen as empty, or in any case far less attractive than the kind of society we could obtain by having a government based on citizens’, not corporations’ interests.

Long-term perspective. Clearly another way to acquire more a accurate perception of the payoff structure, so as to better see the benefits of cooperation by voting for third-party candidates, is to adopt a long-term perspective. A bias favoring immediate wishes over long-term welfare is, of course, a fundamental problem of human nature. But the problem is especially great in politics, where demagogues and news media specialize in appealing to voters’ short-term interests. In any given election, the short term benefits promised by Republican and Democrat candidates may seem attractive to their respective constituencies, but over the course of 10 or 20 years alternations of policy and failure to pursue any consistent course is disastrous.

Collectivize utilities. By collectivizing utilities I mean for individual citizens to recognize their own best interests and those of their fellow Americans are intimately connected. We are a highly interdependent society. Ultimately, social injustice or unfair distribution of wealth harms everyone. If one segment of the population is oppressed or excluded, or their views ignored, then at the very least their contribution to society will be lessened, and this hurts everyone. Moreover, eventually an oppressed or underserved group will gather sufficient energy to redress the wrong by political action. Whatever is at the basis of the ideological split between Republicans and Democrats, the current political dynamics operate as a negative feedback system: as one group gains successive victories, opposing pressure builds until a reversal occurs. Thus victories are often short-lived, policies flip-flop, and no sustained course is pursued.

Consider higher-order utilities. The utility calculus of voters is such that typically only material values – jobs, benefits, taxes, etc. – are considered. Americans have bought lock, stock and barrel the political lie that “it’s the economy, stupid”, i.e., that all success and value of our society is measured by the GNP. This does not reflect the true value structure of human beings. We are not merely material creatures, but moral and spiritual beings as well. It is an undeniable fact that people feel good and experience more happiness and satisfaction when they practice generosity, altruism, benevolence, charity, and justice. Add to this that no amount of material benefits can outweigh the disadvantages of citizens being constantly at each others’ throats. In an authentic utility calculus, higher-order utilities have to be considered; and if they are, the payoff much more clearly favors cooperation among voters and rejection of the two-party hegemony.

Third-party platforms and rhetoric. Third parties must confront Americans with the price being paid for two-party totalitarianism and emphasize that a better future is obtainable.

Voter pacts. Beyond changing perceptions of payoffs, there are active steps that people in a prisoners’ dilemma can do to win the game. Perhaps the most obvious is for the two players to anticipate the dilemma and form a pact beforehand. For example, with regards to Table 1, you and your friend could agree beforehand, “If we’re caught, we both promise to assert our innocence.” This solution is enhanced by establishing or improving trust, affection, and bonds of unity between the two players.

In theory, individual Republican and Democrat voters could pair up with a member of the opposite party and agree to vote for third-party candidates. A website might be set up for this purpose. While this is sensible and ethical, I believe that at least certain forms of voting pacts have been ruled illegal, and one website dedicated to this was forced to close. Nevertheless this principle could doubtless be applied in ways that are unambiguously legal, or at least such that contrary prohibitions would be unenforceable.

Bargains could also be made at the level of institutional endorsements. For example, two newspapers, one liberal and one conservative, could make a pact to endorse third-party candidates.

Opting out. Finally, citizens might opt out of the dilemma in various ways. I would personally not advocate failure to vote as a means for this, although some suggest it. Protests, demonstrations, or even strikes might be used to pressure the Republican and Democratic parties to reform their platforms and supply better candidates. Another possibility is to hold alternative elections run by the citizens themselves with candidates of their own choosing. Such elections would have no legal status, but they would have symbolic value, would permit realistic debates about policy, and encourage trust and camaraderie amongst citizens.

These are only representative suggestions. How feasible or effective any of them would be remains to be seen. The main point here has been to suggest that PD is an appropriate paradigm for looking at the current two-party stranglehold on American society and understanding how to encourage third-party voting. I would like to encourage others, including social scientists, to consider this topic more, as I believe the model is apt and probably contains more theoretical and practical implications than have been considered here.

Post-script

Writing this article helped me to see the more fundamental problem: American society generally is an n-way prisoners’ dilemma. When people view society as merely a ‘dog-eat-dog’ competition, they ‘rationally’ choose to maximize self(ish)-interest. But selfishness only pays off when other people act unselfishly. When everybody acts selfishly, everyone loses; thinking you’ll win by acting selfishly is an illusion.

Each person is better off when everybody cooperates. This is more than an ethical maxim, it’s demonstrated by game theory.

This problem (whether to vote for a third-party candidate, or a less preferred candidate that is more likely to win) is an instance of a more general class of social dilemmas. As such it is not only related to the prisoners’ dilemma but also the tragedy of the commons. Several other forms of insincere voting that constitute social dilemmas. For all such dilemmas, the long-term optimal strategy is cooperation, viz. for each agent to choose so as to maximize long-term collective, not immediate personal utility.

Further Reading

Rapoport, Anatol. Prisoner’s Dilemma: A Study in Conflict and Cooperation. University of Michigan, 1965.

Uebersax, John. The Lions and the Tigers (A Political Parties Fable).

Uebersax, John. Third-Party Voting and Kant’s Categorical Imperative.

Uebersax, John. Voting as Constructive Idealism: Why Principles Do Matter More than Expediency.

Uebersax, John. Why Vote Third-Party?

The Immortal I

The Immortal I

Thank you!

I think we should make it illegal for the States to effectively endorse the two party system by identifying party affiliation on ballots.

dmplantz

pecosthinktank@wordpress.com

dmplantz

June 30, 2013 at 10:24 pm

I am convinced. PD is roughly equivalent to our two-party paradigm. In PD the consequences are usually portrayed as substantial. Reality: our individual vote is inconsequential and the consequences of our collective votes are inconsequential.

We may be at an evolutionary pivot where the costs of voting on principles are so cheap that voters just do it. This might explain why Eric Cantor recently lost a primary to David Brat. Voters might have good or bad principles, but their vote for David Bratt was principled.

Ralph Rader has written about the right capturing a left-right alliance against the government-corporate alliance. He is bemoaning the right capturing a part of the left in principled voting, and is the first to articulate it.

BTW, I discovered this great read trying to find out how people calculate the value of a vote in dollars or percents.

PS, I do not see iterative PD as tit-for-tat, but as a move from from an old paradigm of pre-emptive retribution to a new paradigm of forgiveness,… or maybe a new paradigm of principled non-compliance with authority (no matter what the cost.) The Prisoners’ Dilemma game reduces the analysis of the human spirit to mechanics. Even though this mechanical analysis predicts and explains so much, it doesn’t capture our essence. Won’t everyone be surprised when they find we don’t fit in their game plan?

Mike Montchalin

August 9, 2014 at 12:09 pm

[…] inexorably, though it might have been easily avoided. A tragedy in this technical sense is the prisoner’s dilemma, about which I’ve written […]

Voting as Idealism | Satyagraha

April 26, 2015 at 1:46 am

[…] least one logical fallacy (false dilemma – read about it, how to get out of it, and how the prisoner’s dilemma may impact third parties here). The same argument can be made from Jill’s side, and it might even carry more weight to many at […]

You’re Not Doing Yourselves Any Favors Trying to Shame People… – The Green Map

August 9, 2016 at 4:15 pm

This makes so much sense, thanks for posting. Made me understand both game theory and electoral politics in the US more.

woolgathering798

September 30, 2016 at 1:29 pm

[…] Not convinced? A few arguments I enjoyed: this mathematical analysis of voting, how to make your protest vote count, The wasted vote myth (“Remember, you never decide the winner”—i.e., one vote can’t change an election as big as the presidential election); and food for thought on a voter’s so-called Prisoners Dilemma. […]

Tired of status quo politics? Vote Third-Party – Finding Middle Ground

November 3, 2016 at 10:11 pm

[…] The Prisoner’s Dilemma and Third-Party Voting […]

Third-Party Voting and Kant’s Categorical Imperative | Satyagraha

March 26, 2018 at 3:58 pm

[…] The Prisoners’ Dilemma and Third-Party Voting […]

Why Vote Third-Party? | Satyagraha

March 26, 2018 at 3:59 pm