Posts Tagged ‘stateless society’

The ‘Natural City’ in the Republic: Is Plato Really a Libertarian?

LATO believed that the ideal political situation would be a State with citizens neatly divided into Worker, Soldier, and Guardian classes living and working in harmony under the leadership of a philosopher-king, right? Actually there are good grounds to question whether this is what Plato really means in the Republic.

LATO believed that the ideal political situation would be a State with citizens neatly divided into Worker, Soldier, and Guardian classes living and working in harmony under the leadership of a philosopher-king, right? Actually there are good grounds to question whether this is what Plato really means in the Republic.

Rather, Plato’s remarks in Republic 2.369b et seq. might be taken as his true view of the ideal political arrangement. There, before he mentions any other kind of government, he proposes a system that we might today call a natural law stateless society (or anarchy — but in the sense of having no government institutions, not social chaos). That is, Plato first proposes that if people were content with simple pleasures, they could live happily, in harmony with each other and with nature, and social affairs could be conducted without institutional government.

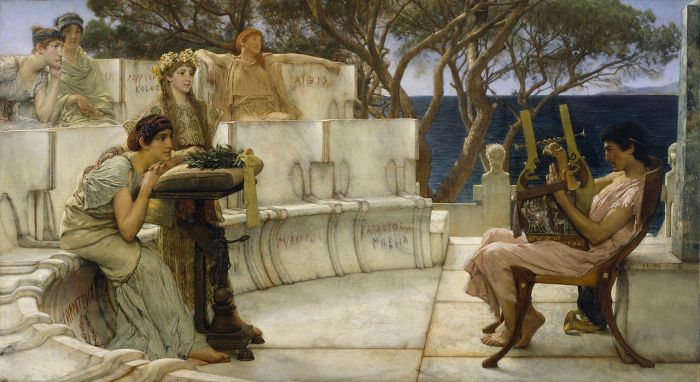

In words that call to mind Hesiod’s myth of the Golden Age (Works and Days 109–142), Socrates here says of such a society, “They and their children will feast, drinking of the wine which they have made, wearing garlands on their heads, and hymning the praises of the gods, in happy converse with one another.” (Rep. 2.372b) He calls this first city the “true and healthy” State.

He elaborates that governments become necessary only when people go beyond necessities and insist on luxuries: delicacies, courtesans, elaborate meals, fancy clothes, and the like (Rep. 2.373a).

His interlocutor, Glaucon, insists that people will not accept such a simple way of life, which he deprecates as a “city of pigs.” Only then does Socrates agree to consider for the remainder of their conversation various forms of the “luxurious State,” which he also calls the fevered or inflamed State (2.372e).

All the famous provisions of the ideal City-State in the Republic — the tripartite division of citizens into Worker, Soldier, and Guardian classes, for example — apply to this second-best State or second city.

Which, then, does Plato recommend? Should we strive for the first, naturalistic city? Or the more luxurious but complex City-State that occupies most of the discussion? Perhaps a clue is found in Socrates’ response to Glaucon’s objection. He never contradicts his original suggestion that the natural city is best. He merely agrees that there is no harm in discussing the luxurious State, because then “we shall be more likely to see how justice and injustice originate.”

Then why, you may ask, does Plato spend so much time in the Republic talking about things like the three classes of citizens, training and education of the Guardians, philosopher-kings, etc.

Possibly because all this pertains to Plato’s use of the Republic as an allegorical analysis of the human psyche, based on the principle of the city-soul analogy. In other words, this later discussion is primarily a psychological allegory — which is the main level at which the Republic is meant to be understood. However — and this is merely a possibility — perhaps Plato could not resist the opportunity to express his true political views briefly, and in an ironic and somewhat cryptic way. Certainly the pacifist themes at the end of these remarks (2.373d-e) would make sense for someone who, as Plato did, grew up during the Peloponnesian War — which was not only pointless to begin with, but resulted in humiliating defeat for Athens, a devastating plague, and massive social upheaval.

But even so, we should also be prepared to interpret this as psychological allegory. Understood in that way, the second city may represent a well-governed soul in search of its lost homeland and its desired state of repose. But once the homeland is reached, happiness is maintained without such strong conscious attention to self-government. That is, one may reach a condition that is the psychic equivalent of Engels’ notion of the withering away of the state (i.e., a perfect utopian society). It might be objected that such a perfect condition is simply impossible — either for an individual or for society — because of imperfections in the nature of each. However in the case of an individual we could allow that such a state may potentially be experienced temporarily (as with a Maslowean peak experience), and, if so, may still be quite valuable for personality integrity and growth. Those familiar with Zen Buddhism might see a possible connection with this mental condition and the 10th image of the Oxherding Pictures (10. ‘Both Vanished’).

Read what Plato wrote and decide for yourself what he means. The passage below is from Benjamin Jowett’s elegant translation of the Republic (1892; italics added). The full citation is: Jowett, Benjamin (ed., tr.). The Dialogues of Plato in Five Volumes. 3rd edition. Vol. 3 – Republic, Timaeus. Oxford, 1892. <http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/166>

[2.372a]

… Socrates. Let us then consider, first of all, what will be their way of life, now that we have thus established them. Will they not produce corn, and wine, and clothes, and shoes, and build houses for themselves? And when they are housed, they will work, in summer, commonly, stripped and barefoot, but in winter substantially clothed and[2.372b]

shod. They will feed on barley-meal and flour of wheat, baking and kneading them, making noble cakes and loaves; these they will serve up on a mat of reeds or on clean leaves, themselves reclining the while upon beds strewn with yew or myrtle And they and their children will feast, drinking of the wine which they have made, wearing garlands on their heads, and hymning the praises of the gods, in happy converse with one another. And they will take care that their families do not exceed their means;[2.372c]

having an eye to poverty or war.But, said Glaucon, interposing, you have not given them a relish to their meal.

True, I replied, I had forgotten; of course they must have a relish — salt, and olives, and cheese, and they will boil roots and herbs such as country people prepare; for a dessert we shall give them figs, and peas, and beans;

[2.372d]

and they will roast myrtle-berries and acorns at the fire, drinking in moderation. And with such a diet they may be expected to live in peace and health to a good old age, and bequeath a similar life to their children after them.Yes, Socrates, he said, and if you were providing for a city of pigs, how else would you feed the beasts?

But what would you have, Glaucon? I replied.

Why, he said, you should give them the ordinary conveniences of life. People who are to be comfortable are accustomed to lie on sofas,

[2.372e]

and dine off tables, and they should have sauces and sweets in the modern style.Yes, I said, now I understand: the question which you would have me consider is, not only how a State, but how a luxurious State is created; and possibly there is no harm in this for in such a State we shall be more likely to see how justice and injustice originate. In my opinion the true and healthy constitution of the State is the one which I have described. But if you wish also to see a State at fever-heat, I have no objection.

[2.373a]

For I suspect that many will not be satisfied with the simpler way of life. They will be for adding sofas, and tables, and other furniture; also dainties, and perfumes, and incense, and courtesans, and cakes, all these not of one sort only, but in every variety; we must go beyond the necessaries of which I was at first speaking, such as houses, and clothes, and shoes: the arts of the painter and the embroiderer will have to be set in motion, and gold and ivory and all sorts of materials must be procured.[2.373b]

True, he said.Then we must enlarge our borders; for the original healthy State is no longer sufficient. Now will the city have to fill and swell with a multitude of callings which are not required by any natural want; such as the whole tribe of hunters and actors, of whom one large class have to do with forms and colours; another will be the votaries of music—poets and their attendant train of rhapsodists, players, dancers, contractors; also

[2.373c]

makers of divers kinds of articles, including women’s dresses. And we shall want more servants. Will not tutors be also in request, and nurses wet and dry, tirewomen and barbers, as well as confectioners and cooks; and swineherds, too, who were not needed and therefore had no place in the former edition of our State, but are needed now? They must not be forgotten: and there will be animals of many other kinds, if people eat them.[2.373d]

Certainly.And living in this way we shall have much greater need of physicians than before?

Much greater.

And the country which was enough to support the original inhabitants will be too small now, and not enough?

Quite true.

Then a slice of our neighbours’ land will be wanted by us for pasture and tillage, and they will want a slice of ours, if, like ourselves, they exceed the limit of necessity,

[2.373e]

and give themselves up to the unlimited accumulation of wealth?That, Socrates, will be inevitable.

And so we shall go to war, Glaucon. Shall we not?

Most certainly, he replied.

Then, without determining as yet whether war does good or harm, thus much we may affirm, that now we have discovered war to be derived from causes which are also the causes of almost all the evils in States, private as well as public.

Undoubtedly.

And our State must once more enlarge;

[2.374a]

and this time the enlargement will be nothing short of a whole army, which will have to go out and fight with the invaders for all that we have, as well as for the things and persons whom we were describing above.

Further Reading

Annas, Julia. The Inner City: Ethics Without Politics in the Republic. In: Julia Annas, Platonic Ethics, Old and New, Ithaca, 1999, pp. 72–95 (Ch. 4).

Guthrie, William K. C. A History of Greek Philosophy. Vol. 4, Plato: The Man and His Dialogues: Earlier Period. Cambridge, 1986. (See pp. 445–449 for an excellent treatment of the topic.)

Uebersax, John S. The Monomyth of Fall and Salvation. 2014.

Uebersax, John S. Psychological Correspondences in Plato’s Republic. 2014.

Written by John Uebersax

January 31, 2015 at 10:35 pm

Posted in Anti-war, Cognitive psychology, Culture of peace, Libertarian, Moral philosophy, Occupy Movement, Occupy Wall Street, Peace, Philosophy, Plato, Plato's Republic, Sapiential eschatology, Social philosophy, Socrates, Statism, The Republic

Tagged with anarchism, libertarianism, Marxism, natural law, stateless society

The Immortal I

The Immortal I

You must be logged in to post a comment.