Welcome to Satyagraha

Welcome to Satyagraha. I hope you find the material here of interest. For more about me and the blog, click here.

John F. Kennedy: We Must Avert Backing Russia into a Corner

THE most famous peace speech of President John F. Kennedy was a commencement address delivered at the American University in Washington, D.C. on June 10, 1963. Selections from the speech particularly relevant to the present world crises are shown below:

I have, therefore, chosen this time and this place to discuss a topic on which ignorance too often abounds and the truth is too rarely perceived — yet it is the most important topic on earth: world peace.

What kind of peace do I mean? What kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, the kind that enables men and nations to grow and to hope and to build a better life for their children not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women — not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.

I speak of peace because of the new face of war. Total war makes no sense in an age when great powers can maintain large and relatively invulnerable nuclear forces and refuse to surrender without resort to those forces. It makes no sense in an age when a single nuclear weapon contains almost ten times the explosive force delivered by all the allied air forces in the Second World War. It makes no sense in an age when the deadly poisons produced by a nuclear exchange would be carried by wind and water and soil and seed to the far corners of the globe and to generations yet unborn. …

I speak of peace, therefore, as the necessary rational end of rational men. I realize that the pursuit of peace is not as dramatic as the pursuit of war — and frequently the words of the pursuer fall on deaf ears. But we have no more urgent task.

Some say that it is useless to speak of world peace or world law or world disarmament — and that it will be useless until the leaders of the Soviet Union adopt a more enlightened attitude. I hope they do. I believe we can help them do it. But I also believe that we must reexamine our own attitude — as individuals and as a Nation — for our attitude is as essential as theirs. And every graduate of this school, every thoughtful citizen who despairs of war and wishes to bring peace, should begin by looking inward — by examining his own attitude toward the possibilities of peace, toward the Soviet Union, toward the course of the cold war and toward freedom and peace here at home.

First: Let us examine our attitude toward peace itself. Too many of us think it is impossible. Too many think it unreal. But that is a dangerous, defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war is inevitable — that mankind is doomed — that we are gripped by forces we cannot control.

We need not accept that view. Our problems are manmade — therefore, they can be solved by man. And man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings. Man’s reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable — and we believe they can do it again.

I am not referring to the absolute, infinite concept of peace and good will of which some fantasies and fanatics dream. I do not deny the value of hopes and dreams but we merely invite discouragement and incredulity by making that our only and immediate goal.

Let us focus instead on a more practical, more attainable peace — based not on a sudden revolution in human nature but on a gradual evolution in human institutions — on a series of concrete actions and effective agreements which are in the interest of all concerned. There is no single, simple key to this peace — no grand or magic formula to be adopted by one or two powers. Genuine peace must be the product of many nations, the sum of many acts. It must be dynamic, not static, changing to meet the challenge of each new generation. For peace is a process — a way of solving problems.

With such a peace, there will still be quarrels and conflicting interests, as there are within families and nations. World peace, like community peace, does not require that each man love his neighbor — it requires only that they live together in mutual tolerance, submitting their disputes to a just and peaceful settlement. And history teaches us that enmities between nations, as between individuals, do not last forever. However fixed our likes and dislikes may seem, the tide of time and events will often bring surprising changes in the relations between nations and neighbors.

So let us persevere. Peace need not be impracticable, and war need not be inevitable. By defining our goal more clearly, by making it seem more manageable and less remote, we can help all peoples to see it, to draw hope from it, and to move irresistibly toward it.

Second: Let us reexamine our attitude toward the Soviet Union. …

No government or social system is so evil that its people must be considered as lacking in virtue. As Americans, we find communism profoundly repugnant as a negation of personal freedom and dignity. But we can still hail the Russian people for their many achievements — in science and space, in economic and industrial growth, in culture and in acts of courage.

Among the many traits the peoples of our two countries have in common, none is stronger than our mutual abhorrence of war. Almost unique among the major world powers, we have never been at war with each other. And no nation in the history of battle ever suffered more than the Soviet Union suffered in the course of the Second World War. At least 20 million lost their lives. Countless millions of homes and farms were burned or sacked. A third of the nation’s territory, including nearly two thirds of its industrial base, was turned into a wasteland — a loss equivalent to the devastation of this country east of Chicago.

Today, should total war ever break out again — no matter how — our two countries would become the primary targets. It is an ironic but accurate fact that the two strongest powers are the two in the most danger of devastation. All we have built, all we have worked for, would be destroyed in the first 24 hours. And even in the cold war, which brings burdens and dangers to so many nations, including this Nation’s closest allies — our two countries bear the heaviest burdens. For we are both devoting massive sums of money to weapons that could be better devoted to combating ignorance, poverty, and disease. We are both caught up in a vicious and dangerous cycle in which suspicion on one side breeds suspicion on the other, and new weapons beget counterweapons.

In short, both the United States and its allies, and the Soviet Union and its allies, have a mutually deep interest in a just and genuine peace and in halting the arms race. Agreements to this end are in the interests of the Soviet Union as well as ours — and even the most hostile nations can be relied upon to accept and keep those treaty obligations, and only those treaty obligations, which are in their own interest.

So, let us not be blind to our differences — but let us also direct attention to our common interests and to the means by which those differences can be resolved. And if we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.

Third: Let us reexamine our attitude toward the cold war, remembering that we are not engaged in a debate, seeking to pile up debating points. We are not here distributing blame or pointing the finger of judgment. We must deal with the world as it is, and not as it might have been had the history of the last 18 years been different.

We must, therefore, persevere in the search for peace in the hope that constructive changes within the Communist bloc might bring within reach solutions which now seem beyond us. We must conduct our affairs in such a way that it becomes in the Communists’ interest to agree on a genuine peace. Above all, while defending our own vital interests, nuclear powers must avert those confrontations which bring an adversary to a choice of either a humiliating retreat or a nuclear war. To adopt that kind of course in the nuclear age would be evidence only of the bankruptcy of our policy — or of a collective death-wish for the world.

Source: John F. Kennedy, Commencement Address at American University, Washington, D.C., June 10, 1963.

❧

Benjamin Franklin on War

Portrait of Benjamin Franklin, Anne-Rosalie Bocquet Filleul (attr.), 1778 or 1779

ASELECTION from the letters of Benjamin Franklin expressing his views on the folly and evils of war.

First, Franklin’s letter to Dr. Richard Price, in 1780. This was in the very midst of the war, and Dr. Price was a London clergyman, a subject of King George; but Franklin and he remained warm friends throughout, and this letter is one of many which Franklin sends from Paris:

We make daily great improvements in natural, there is one I wish to see in moral philosophy: the discovery of a plan that would induce and oblige nations to settle their disputes without first cutting one another’s throats. When will human reason be sufficiently improved to see the advantage of this? When will men be convinced that even successful wars at length become misfortunes to those who unjustly commenced them, and who triumphed blindly in their success, not seeing all its consequences?

In 1782, in a letter from Franklin to Dr. Joseph Priestley upon man’s common inhumanity to man, occurs the following famous passage:

In what light we are viewed by superior beings may be gathered from a piece of late West India news, which possibly has not reached you. A young angel of distinction, being sent down to this world on some important business, for the first time, had an old courier spirit assigned him for his guide ; they arrived over the seas of Martinico, in the middle of the long day of obstinate fight between the fleets of Rodney and De Grasse. When through the clouds of smoke he saw the fire of the guns, the decks covered with mangled limbs, and bodies dead or dying; the ships sinking, burning, or blown into the air; and the quantity of pain, misery and destruction the crews yet alive were thus with so much eagerness dealing round to one another; he turned angrily to his guide and said: “You blundering blockhead! you undertook to conduct me to the earth, and you have brought me into hell!” “No, sir,” says the guide,” I have made no mistake; this is really the earth, and these are men. Devils never treat one another in this cruel manner; they have more sense, and more of what men vainly call humanity.”

The next year, 1783, the treaty of peace was signed which recognized the independence of the United States; and Franklin writes as follows to Sir Joseph Banks:

I join with you most cordially in rejoicing at the return of peace. I hope it will be lasting, and that mankind will at length, as they call themselves reasonable creatures, have reason enough to settle their differences without cutting throats; for, in my opinion, there never was a good war or a bad peace. What vast additions to the conveniences and comforts of life might mankind have acquired, if the money spent in wars had been employed in works of public utility! What an extension of agriculture, even to the tops of the mountains; what rivers rendered navigable, or joined by canals; what bridges, aqueducts, new roads, and other public works, edifices and improvements, rendering England a complete paradise, might not have been obtained by spending those millions in doing good, which in the last war have been spent in doing mischief in bringing misery into thousands of families, and destroying the lives of so many working people, who might have performed the useful labors.

In the same year he wrote from Paris to David Hartley in London:

I think with you that your Quaker article is a good one, and that men will in time have sense enough to adopt it. … What would you think of a proposition, if I should make it, of a compact between England, France and America? America would be as happy as the Sabine girls if she could be the means of uniting in perpetual peace her father and her husband. What repeated follies are these repeated wars! You do not want to conquer and govern one another. Why then should you be continually employed in injuring and destroying one another? How many excellent things might have been done to promote the internal welfare of each country; what bridges, roads, canals and other public works and institutions, tending to the common felicity, might have been made and established with the money and men foolishly spent during the last seven centuries by our mad wars in doing one another mischief! You are near neighbors, and each have very respectable qualities. Learn to be quiet and to respect each other’s rights. You are all Christians. One is The Most Christian King, and the other Defender of the Faith. Manifest the propriety of these titles by your future conduct. “By this,” says Christ, “shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye love one another.” “Seek peace and ensue it.”

In 1783, when peace was uppermost in his thoughts, he wrote also to Mrs. Mary Hewson:

All wars are follies, very expensive and very mischievous ones. When will mankind be convinced, and agree to settle their differences by arbitration? Were they to do it even by the cast of a die, it would be better than by fighting and destroying each other.

Four years later, in 1787, just after the close of the Constitutional Convention, he wrote the following impressive letter to his sister, Mrs. Jane Mecom:

I agree with you perfectly in your disapprobation of war. Abstracted from the inhumanity of it, I think it wrong in point of human providence. For whatever advantages one nation would obtain from another, whether it be part of their territory, the liberty of commerce with them, free passage on their rivers, etc., etc., it would be much cheaper to purchase such advantages with ready money than to pay the expense of acquiring it by war. An army is a devouring monster, and when you have raised it you have, in order to subsist it, not only the fair charges of pay, clothing, provision, arms and ammunition, with numberless other contingent and just charges, to answer and satisfy, but you have all the additional knavish charges of the numerous tribe of contractors to defray, with those of every other dealer who furnishes the articles wanting for your army, and takes advantage of that want to demand exorbitant prices. It seems to me that if statesmen had a little more arithmetic, or were more accustomed to calculation, wars would be much less frequent. I am confident that Canada might have been purchased from France for a tenth part of the money England spent in the conquest of it; And if, instead of fighting with us for the power of taxing us, she had kept us in a good humor by allowing us to dispose of our own money, and now and then giving us a little of hers by way of donation to colleges or hospitals, or for cutting canals or fortifying ports, she might easily have drawn from us much more by our occasional voluntary grants and contributions than ever she could by taxes. Sensible people will give a bucket or two of water to a dry pump that they may afterwards get from it all they have occasion for. Her Ministry were deficient in that little point of common sense; and so they spent one hundred millions of her money, and after all lost what they contended for.

To Alexander Small, in England, he wrote in 1787:

You have one of the finest countries in the world, and if you can be cured of the folly of making war for trade (in which wars more has been always expended than the profits of any trade can compensate) you may make it one of the happiest. Make the most of your own natural advantages, instead of endeavoring to diminish those of other nations, and there is no doubt but that you may yet prosper and flourish. Your beginning to consider France no longer as a natural enemy is a mark of progress in the good sense of the nation.

Finally, in 1788, he wrote as follows to M. Le Veillard in France:

When will princes learn arithmetic enough to calculate, if they want pieces of one another’s territory, how much cheaper it would be to buy them than to make war for them, even though they were to give a hundred years’ purchase? But if glory cannot be valued, and therefore the wars for it cannot be subject to arithmetical calculation, so as to show their advantage or disadvantage, at least wars for trade, which have gain for their object, may be proper subjects for such computation; and a trading nation, as well as a single trader, ought to calculate the probabilities of profit and loss before engaging in any considerable adventure. This, however, nations seldom do, and we have had frequent instances of their spending more money in wars for acquiring or securing branches of commerce than a hundred years’ profit or the full enjoyment of them can compensate.

Source: Mead, Edwin D. Washington, Jefferson and Franklin on war. World Peace Foundation Pamphlet Series. Boston, May 1913; pp. 7−10.

❧

What Ended the Golden Era of Peace Activism (1810−1850)?

THE period from 1810 to 1850 can be truly called a golden age of peace activism in the United States and England. In response to the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the War of 1812 in America, many articles and pamphlets began to appear that denounced war. From about 1815, calls appeared to for creation of local peace societies. Eventually hundreds of such such societies emerged, the most influential being the Massachusetts Peace Society, the London Peace Society and the American Peace Society.

The movement as a whole had many notable achievements, including getting serious attention by government officials, shaping public opinion, organizing large protests, and eventually sponsoring three international congresses. However after 1850, in both the US and England, the movement began to lose force and never fully recovered. Today relatively few people — even antiwar activists — are familiar with this important part of history.

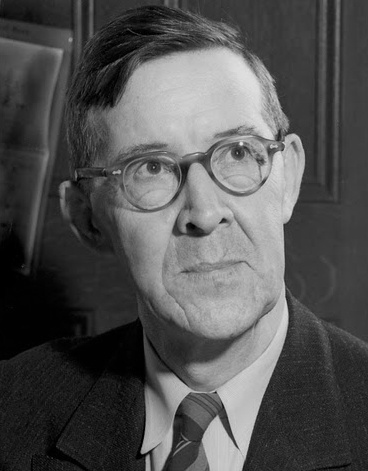

The historian Merle Curti, in a book devoted to this movement, mentions several possible reasons why the movement effectively ended. These are of more than mere historical interest: they should be considered in relation to the need to create a similarly effective organized movement today.

Briefly, the reasons for the movement’s waning include:

Reliance on charismatic leaders. The main figures in the peace movement — for example Noah Worcester and William Ladd in the US — were driven by immense passion and conviction and were tireless workers. Ladd, in particular, sacrificed not only his fortune but his health in his efforts. When this generation of leaders died, the movement lost force. Such is probably the pattern of many social movements.

Aging membership. Along with this was a gradual aging of the movement’s original members. It couldn’t replenish its ranks by interesting younger people to join.

Disillusionment. In England the bloody Crimean War first shook activists’ confidence, and then war piled upon war. Some became disillusioned; others succumbed to the growing war spirit.

Conflict with other ideals. Curti suggests that nationalism and liberalism became stronger ideals than peace. These movements not only drew away potential antiwar activists, but (as in the case of nationalist revolutions) sometimes made war seem justified. This remains a consideration today, as many people whom one might expect to support the cause of peace consider things like “democracy” and “social justice” legitimate reasons for aggression.

American Civil War. The Civil War effectively ended the peace movement in the US. For many, slavery was considered an evil sufficiently great to justify war.

Indifference of churches. Despite the fact that the founders of the movement were Christian and, at least initially, based their position on Christian teachings, they were never able to interest Christian churches at large. Unfortunately, the same remains true today.

Pendulum effect. Partly this occurred as an inevitable return swing of the pendulum. Any new social or intellectual movement meets with resistance. The struggle for peace cannot be accomplished quickly. One can only hope that over time gains will be greater than losses.

Internal friction. From the outset the movement was divided on the issue of defensive wars. Strict pacifists insisted that all war was wrong. Others contended that war in self-defense was legitimate. Pacifists countered that any war could be justified if one grants the principle of defensive war. There never was any solution to this split and it weakened the movement as a whole.

While the movement didn’t last, Curti also notes two important accomplishments. First, it produced solid arguments against war:

Perhaps the most striking contribution of early organized pacifism was the development of a body of brilliant arguments against war. By 1860 practically every argument against war now familiar had been suggested, and almost every current plan for securing peace had been at least anticipated. While the arguments against war in the earlier years were chiefly religious, moral, and philanthropic, they tended to become less and less an expression of the general spirit of liberalism and romanticism. They tended to become increasingly realistic and to make greater use of economic and political considerations. This was in part due to the working alliance of the free traders and peace men in England and to the influence of French socialist thought on the opponents of war. Increasing attention was given, for example, to the wastefulness of war and to the burdens it inflicted on the working classes. Much emphasis was put on the desirability of developing closer economic ties, bankers’ agreements for the refusal of war loans, workingmen’s international associations, and other types of economic federations. By 1850 Elihu Burritt had urged that an organized general strike of the workers of the world against war was the only possible alternative to a court and congress of nations. (Curti, p. 225)

Second, they developed practical plans for the achievement of peace:

A fourth important contribution of the early crusade for peace was the working out of definite practical plans looking toward the ultimate establishment of world peace. The plan for the inclusion in international treaties of stipulated arbitration clauses was first advanced by an American, William Jay, and was vigorously supported both here and abroad. The most important practical plan, however, was William Ladd’s scheme for a court and congress of nations …. Plans were also made for the codification of international law, for disarmament, and for the development of internationalism through educational and other projects. (Curti, p. 226)

On this web page are some of the more important essays and sermons produced by the movement, along with a bibliography.

Bibliography

Uebersax, John. Essays and Speeches from the Antebellum Era (c.1800–1850) Peace Movement (online collection, with bibliography)

Curti, Merle Eugene. The American Peace Crusade 1815-1860. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1929.

❧

The Congress−Military−Industrial Complex

WAR is not only the greatest moral evil, but the greatest economic evil as well.

Why do wars continue? We must ask the question, cui bono — who benefits? The answer is clear: US defense contractors reap billions of dollars annually producing advanced weapons. If we stopped war, these huge corporations would go out of business. They exert immense political leverage to control the foreign policy of the US to promote wars and a climate of international mistrust and fear.

But members of Congress all too willingly play along. They receive millions of dollars annually from companies like Lockheed-Martin, Boeing, Raytheon and Northrop Grumman in the form of campaign contributions. Then they boast to their constituents about how many jobs are being created to build aircraft carriers and nuclear missiles.

This book, The Politics of Defense Contracting by Gordon Adams is a seminal study of the Congress−military−industrial complex, or the iron triangle:

This is the first systematic study of the relationship between government and defense contractors, examining in detail the political impact of the eight most powerful defense contractors. It details ways in which Boeing, General Dynamics, Grumman, McDonnell Douglas, Northrop, Rockwell International, and United Technologies influence government, from their basic contract activity, corporate structure, and research efforts, to their Washington offices, Political Action Committee campaign contributions, hiring of government personnel, and membership on federal advisory committees. Adams concludes with specific recommendations for changes in disclosure requirements that would curb some of the political power corporations can wield. It also suggests specific ways in which the Iron Triangle can be made subject to wider congressional and public scrutiny.

You can browse the book at Amazon.com.

❧

A Week − Thoreau’s Spiritual Odyssey

“Bear in mind. Child, and never for an instant forget, that there are higher planes, infinitely higher planes, of life than this thou art now travelling on. Know that the goal is distant, and is upward, and is worthy [of] all your life’s efforts to attain to.” (Journal, vol. II, 497)

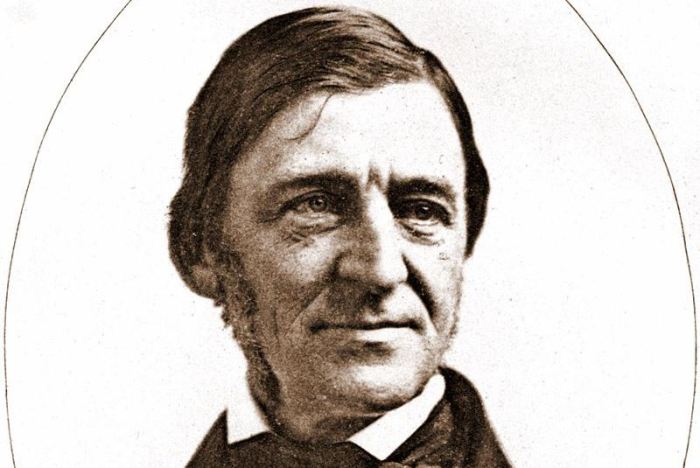

HENRY DAVID THOREAU, alas, is too often seen as almost a one-hit-wonder. Walden is revered as a great work of literature. His second most famous work, On Civil Disobedience, is respected, but almost more as a political manifesto than as literature per se. Few read his poems, journals or essays.

Yet there is good reason to regard A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers as a literary masterpiece equal to, if not even surpassing Walden.

It was not received well on its initial publication, and Thoreau re-wrote it twice. Even the third version, published at his own expense, fared poorly: the publisher sent 3/4 of the volumes back to him unsold.

The work was plainly a labor of love for Thoreau. He spent nearly a decade on it. Emerson thought highly of it, but the critics did not. They complained of its unorthodox style — a travel narrative interspersed with various anecdotes, poems and ‘stray’ philosophical thoughts.

In the 20th century a more favorable view emerged. People began to see that everything in A Week was connected. There is a sublime unity, and the theme is spirituality. It is not a literal narrative of a journey up and down a river, but a parable for the soul’s journey, its immortal destiny. Lawrence Buell devotes a chapter to it, referring to Thoreau’s aim “to immortalize the excursion, raising it, in all its detail, to the level of mythology,” and calling it the “most ambitious literary work the Transcendentalist movement produced” (p. 144).

Thoreau used the story of his trip with his brother John — who died tragically not long after the events — to work through his grief, and arrive at a firm hope in a life beyond this one. Moreover, as artist, poet and prophet, he wished to communicate a deep message to his readers.

Whether A Week is a great work, whether he succeeded like the ancient Greek poets he so admired in producing an immortal work, I leave it up to you to decide. But it is a beautiful and haunting work in any case. The spiritual dimension is superbly revealed by Klaus Ohlhoff in his master’s thesis. I have never seen a thesis more insightful and artistically composed than this. Chapter 2 ought to have been published as a standalone essay, but apparently never was.

Trust me. If you love Thoreau (and many do, of that I am certain), you will appreciate this Ohlhoff’s chapter. I will not spoil it by quoting from it, nor cite or relevant passages from A Week. If you’ve ever read A Week or ever plan to — I would simply urge you to read Ohloff’s study.

References

Adams, Raymond W. Thoreau and Immortality. Studies in Philology, vol. 26, no. 1, 1929, pp. 58–66.

Bishop, Jonathan. The Experience of the Sacred in Thoreau’s Week. ELH, 33, March 1966.

Buell, Lawrence. Literary Transcendentalism: Style and Vision in the American Renaissance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973; Chapter 8, Thoreau’s A Week (pp. 208−238).

Ohlhoff, Klaus W. Thoreau’s Quest for Immortality. Diss. Lakehead University, 1979; Chapter 2 (pp. 63–144).

Paul, Sherman. The Shores of Africa: Thoreau’s Inward Exploration. Urbana; University of Illinois Press, 1958.

Thoreau, Henry David. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. New York: Crowell, 1911.

❧

Flowers — Stars of the Earth

THIS wonderful eulogium on flowers — arguably the best ever written — was excerpted many times throughout the 19th century, but never with the author’s name. Today well known quotes from it are wrongly attributed to Clara Lucas Balfour and others. A little research has found that the original author is William Pitt Scargill (1787–1836), an English Unitarian minister and writer. The is published below in its entirety for the first time since 1853.

❧

A Chapter on Flowers

WHAT is the use of flowers? Why cannot the earth bring forth the fruits that feed us, and the sweet flavours that provoke our appetite, without all this ostentation? What is it to the ponderous cow, that lies ruminating and blinking hour after hour on the earth’s green lap, that myriads of yellow buttercups are all day laughing in the sun’s eye? Wherefore does the violet, harbinger of no fruit, nestle its deep blueness in the dell, and fling its wanton nets of most delicious fragrance, leading the passenger by the nose? And wherefore does the tulip, unedible root, shoot up its annual exhibition of most gaudy colour and uninterpretable beauty? Let the apple-tree put forth her blossom, and the bean invite the vagrant bee by the sweet annunciation of coming fruit and food; — but what is the use of mere flowers — blossoms that lead to nothing but brown, withered, curled-up, vegetable fragments? And why is their reign so short? Why does the gum-cistus drop its bright leaves so regularly at such brief intervals, putting on a clean shirt every day? Who can interpret the exception to the rule of nature’s plan of utility? For whom are flowers made, and for what? Are they mere accidents in a world where nought else is accidental? Is there no manifestation of design in their construction? Verily they are formed with as complete and ingenious a mechanism as the most sensitive and marvellous of living beings. They are provided with wondrous means of preservation and propagation. Their texture unfolds the mystery of its beauty to the deep-searching microscope, mocking the grossness of mortal vision. Shape seems to have exhausted its variety in their conformation; colour hath no shade, or combination, or delicacy of tint, which may not be found in flowers; and every modulation of fragrance is theirs. But cannot man live without them? For whom, and for what, are they formed? Are they formed for themselves alone? Have they a life of their own? Do they enjoy their own perfume, and delight themselves in the gaudiness of their own colours and the gracefulness of their own shapes? Man, from the habitual association of thought, sentiment, and emotion — with eyes, nose, and mouth, and the expression of the many-featured face, cannot conceive of sense or sentiment subsisting without these modifications, or some obvious substitute for them. Is there nothing of expression in their aspect? Have they not eyeless looks and lipless eloquence? See the great golden expanse of the sun-flower winding, on its tortuous stem, from east to west; praising, in the profuseness of its gaudy gratitude, the light in which it lives and glories. See how it drinks in, even to a visible intoxication, the life-giving rays of the cordial sun; while, in the quiet of its own deep enjoyment, it pities the locomotive part of the creation, wandering from place to place in search of that bliss which the flower enjoys in its own bed; fixed by its roots, a happy prisoner, whose chains are its life. Is there no sense or sentiment in the living thing? Or stand beneath the annual canopy that o’ershadows a bed of favourite and favoured tulips, and read in their colours, and their cups, the love they have for their little life. See you not that they are proud of their distinction? On their tall tremulous stems they stand, a11 it were, on tiptoe, to look down on the less favoured flowers that grow miscellaneously rooted in the uncanopied beds of the common garden. Sheltered and shielded are they from the broad eye of day, which might gaze on them too rudely; and the vigour of their life seems to be from the sweet vanity with which they drink in admiration from human eyes, in whose milder light they live. Go forth into the fields and among the green hedges; walk abroad into the meadows, and ramble over heaths; climb the steep mountains, and dive into the deep valleys; scramble among the bristly thickets, or totter among the perpendicular precipices; and what will you find there? F1owers — flowers — flowers! What can they want there? What can they do there? How did they get there? What are they but the manifestation that the Creator of the universe is a more glorious and benevolent Being than political economists, utilitarians, philosophers, and id genus omne?

Flowers — of all things created most innocently simple and most superbly complex: playthings for childhood, ornaments of the grave, and companions of the cold corpse in the coffin! Flowers — beloved by the wandering idiot and studied by the deep-thinking man of science! Flowers — that of perishing things are most perishing, yet of all earthly things are the most heavenly! Flowers — that, in the simplicity of their frailty, seem to beg leave to be, and that occupy, with blushing modesty, the clefts, and corners, and spare nooks of earth, shrinking from the many-trodden path, and not encroaching on the walks of man; retiring from the multitudinous city, and only then, when man has deserted the habitation he has raised, silently, and as if long waiting for implied permission, creeping over the grey wall and making ruin beautiful! Flowers — that unceasingly expand to heaven their grateful, and to man, their cheerful looks: partners of human joy, soothers of human sorrow; fit emblems of the victor’s triumphs, of the young bride’s blushes; welcome to crowded balls and graceful upon solitary graves! Flowers — that, by the unchangeableness of their beauty, bring back the past with a delightful and living intensity of recollection! Flowers — over which innocence sheds the tear of joy; and penitence heaves the sigh of regret, thinking of the innocence that has been! Flowers are for the young and for the old; for the grave and for the gay; for the living and for the dead; for all but the guilty, and for them when they are penitent. Flowers are, in the volume of nature, what the expression, “God is love,” is in the volume of revelation. They tell man of the paternal character of the Deity. Servants are fed, clothed, and commanded; but children are instructed by a sweet gentleness; and to them is given, by the good parent, that which delights as well as that which supports. For the servant there is the gravity of approbation or the silence of satisfaction; but for children there is the sweet smile of complacency and the joyful look of love. So, by the beauty which the Creator has dispersed and spread abroad through creation, and by the capacity which he has given to man to enjoy and comprehend that beauty, he has displayed, not merely the compassionateness of his mercy, but the generosity and gracefulness of his goodness.

What a dreary and desolate place would be a world without a flower! It would be as a face without a smile — a feast without a welcome. Flowers, by their sylph-like forms and viewless fragrance, are the first instructors to emancipate our thoughts from the grossness of materialism; they make us think of invisible beings; and, by means of so beautiful and graceful a transition, our thoughts of the invisible are thoughts of the good.

Are not flowers the stars of earth, and are not stars the flowers of heaven? Flowers are the teachers of gentle thoughts — promoters of kindly emotion. One cannot look closely at the structure of a flower without loving it. They are emblems and manifestations of God’s love to the creation, and they are the means and ministrations of man’s love to his fellow-creatures; for they first awaken in the mind a sense of the beautiful and the good. Light is beautiful and good: but on its undivided beauty, and on the glorious intensity of its full strength, man cannot gaze; he can comprehend it best when prismatically separated and dispersed in the many-coloured beauty of flowers; and thus he reads the elements of beauty — the alphabet of visible gracefulness. The very inutility of flowers is their excellence and great beauty; for, by having a delightfulness in their very form and colour, they lead us to thoughts of generosity and moral beauty detached from and superior to all selfishness; so that they are pretty lessons in nature’s book of instruction, teaching man that he liveth not by bread or for bread alone, but that he hath another than an animal life.

It is a pretty species of metaphysics which teaches us that man consists of body, soul, and spirit, thus giving us two parts heavenly for one that is earthly, the intermediate leading us by a gentle ascent to the apprehension and enjoyment of the higher part of our nature; so taste and a love of the beautiful leads us to the aspiring after virtue, and to regarding virtue as something far sublimer than mere calculation of physical enjoyment. Is not the very loveliness of virtue, its disinterestedness, its uncalculating generosity, its confiding freeness, its apprehension of a beauty beyond advantage and above utility — above that utility which ministers merely to the animal existence? In its highest and purest sense, utility is beauty, inasmuch as well-being is more than being, and soul is more than body. Flowers, then, are man’s first spiritual instructors, initiating him into the knowledge, love, and apprehension of something above sensualness and selfishness. Children love flowers, childhood is the age of flowers, of innocence, and beauty and love of beauty. Flowers to them are nature’s smiles, with which they carl converse, and the language of which they can comprehend, and deeply feel, and retain through life; so that when sorrow and a hard lot presses on them heavily in after years, and they are ready to think that all is darkness, there springs up a recollection of an early sentiment of loveliness and recollected beauty, and they are reminded that there is a spirit of beauty in the world, a sentiment of kindness that cannot be easily forgotten, and that will not easily forget. What, then, is the use of flowers? Think of a world without flowers — of a childhood that loves them not-of a soul that has no sense of the beautiful — of a virtue that is driven and not attracted, founded on the meanness of calculation, measuring out its obedience, grudging its generosity, thinking only of its visible and tangible rewards; think of a state of society in which there is no love of beauty, or elegance, or ornament; and then may be seen and felt the utility of ornament, the substance of decoration, the sublimity of beauty, the usefulness of flowers.

~ William Pitt Scargill, 1832.

Bibliography

Dwight, John Sullivan. The Religion of Beauty, Dial, July 1840, pp. 17-22.

Plotinus. Enneads 1.6 (On Beauty), tr. Stephen McKenna, 1917.

Scargill, William Pitt. A Chapter on Flowers. Amulet, vol. 7, 1832, 151−158.

Uebersax, John (ed.). Florigelium: 100 Best Inspirational Quotes About Flowers and Their Beauty. 2022.

❧❧

The Immortal I

The Immortal I

You must be logged in to post a comment.