Archive for the ‘Social philosophy’ Category

Inspired Literature (reposted)

Simone Cantarini, Saint Matthew and the Angel, Italian, 1612 – 1648, c. 1645/1648, oil on canvas.

IN ONE of his more famous writings, William Ellery Channing addressed the topic of developing a uniquely American intellectual tradition. His message is important today in several respects. One of his chief concerns was to counter the growing tide of materialism in Europe and America. This, he believed, could only end in, at the individual level, unhappiness, and, at the collective level, dehumanizing institutions and dysfunctional government. Sound literature, he maintains, is founded on genius, which is itself activated when our hearts and minds are aligned with our moral and spiritual nature. Genius does not manifest itself in a vacuum, however: inspired writers write inspiredly when there is an audience capable of receiving an inspired message. Hence our first need is to morally prepare the public. This, Chandler, argues, is the proper role of religion. But religion itself must be of a higher quality. Instead of religion based on formality, authority, dogma or superstition, we need one based on personal spiritual experience and authentic moral consciousness. . . . read full article here (re-posted from my Christian Platonism blog)

Written by John Uebersax

July 13, 2022 at 1:14 am

Posted in American Transcendentalism, consciousness, Cultivation of the Intellect, Cultural psychology, Culture, Idealism, Literature, Materialism, Moral philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, religion, Renewing America, Scholarship, Self-culture, Social philosophy, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values

Tagged with Genius, Inspiration, religious experience, religious reform, William Ellery Channing

Transcendentalism Timelines

HERE are two timeline charts that relate to New England Transcendentalism.The first, above, shows the dates of major figures in the movement. Not everyone may agree with my choices here. For example, Walt Whitman, and even more, Emily Dickinson, are not usually considered part of the main Transcendentalist movement. However my own opinion is that poetry (as Emerson many times emphasized) is so important to the message of Transcendentalism that we can risk erring in the direction of potential over-inclusion of poets.

The second figure, below, summarizes key 18th century European influences on New England Transcendentalism. As shown, these include German idealism (Kant, Schelling, etc.), German Romanticism (Goethe, De Stael), ‘English’ Transcendentalism (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Carlyle [these are not really “18th century” influences]), and Swedenborg.

The first figure shows some interesting things. One is the high proportion of Unitarian ministers. Many of these were Christian Unitarians. This somewhat contradicts the ‘received opinion’ that Transcendentalism was fundamentally non- or even anti-Christian. The relationship between Transcendentalism and Christianity is a highly nuanced issue that has been insufficiently studied. Second, we see a definite ‘golden age’ of Transcendentalism between roughly, 1836 and 1855. This period contains most of the publications emblematic of the movement. However Emerson remained a popular and active lecturer into the 1870’s (even travelling to California). Moreover, Amos Bronson Alcott’s Concord School of Philosophy operated up to the last decade of the 19th century.

Another interesting detail is that, although there is a tendency to think of Whitman as a more modern figure than Thoreau, they were born only a year apart, and Leaves of Grass appeared the year after Walden.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

July 2, 2022 at 7:16 pm

Dial (1840−1844) − Complete Edition

THE seminal New England Transcendentalist periodical Dial, published from 1840 through 1844, is a milestone in the history of American literature, philosophy and intellectual life. It’s something not only of historical interest, but a living part of American consciousness. The ideas were to lofty to have much direct impact then, but they await and invite rediscovery by new generations.

To the best of my knowledge, the complete four volumes have never been printed in their entirety, except for a very limited edition in 1902. Moreover, many of the fine essays and poems do not exist in machine readable form. I have hopefully met the need by taking four scanned volumes available from Google Books, converting them with optical character recognition to machine readable form, placing them in a single, bookmarked pdf file, and adding author information not in the original volumes. The free pdf ebook can be downloaded here.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

June 28, 2022 at 2:10 am

What American Transcendentalism is Not

Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1859

THERE is today in the United States a severe cultural crisis that involves a loss of morale, hope and meaning. This probably affects most of all young adults, who have their whole lives ahead of them, and yet must face problems like student loan debt, lack of adequate jobs, unaffordable housing, and completely dysfunctional politics, coupled with an absence of meaningful creativity in literary and artistic sectors of society.

Behind all these problem is a more fundamental one: that the cultural mentality in the West today is one of radical materialism — and materialism, by its very nature, robs life of true meaning. If radical materialism is the malady, then a return to cultural Idealism is the remedy. No only common sense, but also — as we have often discussed at Satyagraha — the theories and historical research of the sociologist Pitirim Sorokin give us some grounds for optimism that a more Idealistic society may emerge from modern materialism.

One way to promote a return to Idealism is to re-familiarize ourselves with the great tradition of American Transcendentalism. This has several advantages. First, Transcendentalism[1] is an indigenous, Americanized Idealism, peculiarly suited to our own unique circumstances, history and potentials as a nation. Second (and partly for the preceding reason), while it has faded from view, it has merely been submerged rather than entirely eliminated from the collective consciousness — as evidenced by such examples as that, even if nobody bothers to read them, we still name streets after Emerson and Thoreau and their portraits hang in the halls of university English Departments.

Young adults today, then, ought to understand what American Transcendentalism is. Then they will at least know there is a coherent and achievable alternative to a materialistic culture. One obstacle, however, is that explaining Transcendentalism (or even defining the term) is notoriously difficult. Part of the problem is that we are dealing with a cultural mentality, including states of consciousness, which are by their nature ‘intangible’ and therefore inherently difficult to literally define.

However perhaps we can be clever here, and approach the issue indirectly. That is, let’s try here not to define what Transcendentalism is, but what it isn’t. That will get us partway to the goal, and in the process can help eliminate certain specific misconceptions that may impede gaining a proper understanding.

Turning, then, to that supremely authoritative source of misinformation, the Google search page, we see that in response to the question “What is American Transcendentalism” it says: “Key transcendentalism [sic] beliefs were that: (1) humans are inherently good but can be corrupted by society and institutions; (2) insight and experience are more important than logic; (3) spirituality should come from the self, not organized religion; and nature is beautiful and should be respected.”

Let’s look at each statement in turn and examine how it is true, false, incomplete, or potentially misleading.

Humans are inherently good but can be corrupted by society and institutions.

The bland statement ‘humans are innately good’ is something more like Rousseau would say. Transcendentalists held much stronger beliefs: that humans are divine, with immortal souls and godlike potentials. We are, as Emerson put it, ‘gods in ruins.’ That is, we fail to live up to our divine potential. The proper remedy is moral, intellectual and spiritual self-culture. Each individual has a solemn moral duty for such self-cultivation.

To say that human beings’ corruption comes from society and institutions is, again, Rousseauian. For Transcendentalists, it is we are ourselves who are to blame for our failures. In a characteristically Platonic fashion (Plato is the dominant philosophical influence on Transcendentalists), the human soul is understood as fallen — not because of external forces, but from insufficient personal virtue and wisdom. Transcendentalists certainly wished to reform and make more just government and society. But this supposes that a free individual can elevate himself or herself to be an agent of change, despite the opposing influences of current institutions.

Insight and experience and more important than logic.

This is basically true, but incomplete. Transcendentalists saw themselves as reacting to the narrow rationalist mentality associated with John Locke and his followers. This empirical/rationalist worldview became increasingly dominant throughout the 18th and into the 19th century. It created, in the opinion of Transcendentalists, a mechanical perspective of life — a utilitarian society where money counts more than meaning, the end always justifies the means, and atheism displaces religion in human affairs.

It is also true that Transcendentalists highly valued ‘experience.’ They saw modern man as living life abstractly — one step removed from reality (as Emerson put it, “living second-hand.”) We respond not to things as they are, about according to rational theories that are, by their nature, limiting and distortive.

Similarly, insight was vital for Transcendentalists. This is an essential feature of Idealism, generally. Insight pertains to realms of knowledge we have that have no connection with the sensory or material world, but instead concern what we see about our own nature by looking within.

Spirituality should come from the self, not organized religion.

Implicit in this statement — but it needs to be stated explicitly — is that Transcendentalists staunchly affirmed that spirituality ought to be central in our lives. As to the view of organized religion, Transcendentalists were divided on this point. Some, like Emerson and Thoreau, had little use for organized religion. Others, however, maintained affiliations with the Unitarian and, in some cases, Congregational or Episcopal denominations.

The central issue is not organized religion, but dogmatized religion. The essential point Transcendentalists wished to affirm (which is the same affirmation made by mystics of all religious throughout the ages) is that personal spiritual experience matters more than imposed literal doctrine. A preacher or catechism can insist, “God is Love” — yet that carries far less force than having the direct experience of God as Love. In the final analysis, doctrine and personal experience are not mutually exclusive. Doctrine can be useful in order that, as St. Augustine taught, belief may lead to experience. However what is clear — and is the real issue here — is that an overemphasis on doctrine has the potential to crowd out and lessen the potential for direct religious experience.

Nature is beautiful and should be respected.

Again, this is a weak and even revisionist version of what Transcendentalists actually believed. To say that ‘nature is beautiful’ would hardly distinguish them from any other movement or segment of humanity. What they actually believed — and what does make them relevant today — are stronger propositions: (1) that Nature has a spiritual basis; (2) that it is a manifestation of God, and of God’s Goodness and Love; (3) that it is also an externalization of our own soul; (4) and that Nature is like a book, intended in every detail to teach us spiritual lessons.

Therefore Nature should indeed be ‘respected’ — but not merely in the sense of that modern environmentalists might understand this. We should most respect Nature precisely because it is a means of understanding (and relating to) God and ourselves. This necessarily implies a strong commitment to protect the natural environment; indeed, it increases our incentive to do so.

Moreover, we must not only respect Nature, but experience it. So, for example, while we should preserve forests and wildernesses, part of the reason for doing this is so that we can visit and receive inspiration from them. To merely preserve and completely isolate from all human contact some natural area, while something a modern environmentalist may consider, would make much less sense to a Transcendentalist.

In sum, the main difficulty here is that any 20th or 21st ‘official’ definition (such as might appear in an online article or university text) of Transcendentalism will necessarily be revisionist. Materialism is so strongly engrained in the modern cultural mentality that one cannot explain Idealism without sounding superstitious or atavistic. There is some kind of unwritten consensus that we are not allowed to conduct serious public discussions on the premises that God exists and the human soul is immortal. Yet without these premises Transcendentalism and Platonic Idealism cannot be understood or appreciated. American Transcendentalism, then, is a great challenge to modernism: it starkly confronts us with the arbitrariness of the assumptions of materialism and atheism. It shows us that a great generation of thinkers were able to develop from these premises a philosophy of life both meaningful and with far-reaching practical significance.

Another important issue with the simplified description of Transcendentalism we’ve considered here is the omission of any reference to the literary interests of this group. These were not people who merely had ecstatic nature experiences. Almost without exception they applied themselves to make significant contributions to literature and education, and to the moral edification of others. Integral to the Transcendentalist personality was the notion of harnessing the creative inspirations and energies of ‘innate genius’ in productive ways to actively contribute to the positive transformation of society.

In the near future I hope to try again to write a brief post dedicated to positively defining the key beliefs of Transcendentalism, but let this suffice for now. Ultimately, the main way to understand it is to read main works of Transcendentalist literature. Some recommended selections may be found in the Bibliography of this earlier article.

Note. 1. Herein for convenience the terms ‘American Transcendentalism’ and ‘Transcendentalism’ are used interchangeably; there are, of course, other versions of transcendentalist or Transcendentalist philosophy.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

June 19, 2022 at 9:35 pm

Posted in American Transcendentalism, consciousness, Cultivation of the Intellect, Cultural psychology, Culture, Idealism, Literature, Materialism, modernism, Moral philosophy, Philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, Plato, Renewing America, Self-culture, Social philosophy, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values

Tagged with mystical experience, transcendence

Aesthetic Education

HERE is an excellent speech, Artistic and Moral Beauty, delivered by Megan Beets Dobrodt at a Feb. 16, 2019 conference sponsored by the Schiller Institute. I recommend watching the video, but the text can also be found in this article.

The basic premise of the speech is that paying more attention aesthetic education and exposure to Great Art will help to produce the positive transformation needed today to keep society from sliding into an abyss.

She first diagnoses the situation of modern society, then offers a solution.

The diagnosis is that: (1) modern society is in desperate shape; (2) government cannot solve our problem; (3) therefore the solution must come from individuals; (4) but individuals minds are held captive and rendered helpless by, among other things, modern films, music, art, etc., which debase and degrade us, and have as their common denominators banality, bestiality and violence

The solution she finds with reference to the philosophical writings of Friedrich Schiller, most notably his Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man: (1) within every human being there already exists the image of the Ideal Man; (2) Great Art appeals to the inner Ideal Man, helping to awaken and activate it; (3) therefore we should expose ourselves to Great Art; and (4) habituate our minds to creative accomplishment. A society composed of such empowered individuals can solve the myriad problems we face today.

Implicit in all this is the Platonic notion of the coincidence of the True, the Beautiful and the Morally Good. When we awaken our aesthetic consciousness, we simultaneously awaken wisdom, scientific creativity, and our deepest moral sense.

There are clear connections with what she says and comments we’ve made here recently concerning the theories of Pitirim Sorokin. Sorokin likewise emphasized the connection between altruism, creativity and what he called the supraconscious.

Many today, like Ms. Beets and the Schiller Institute, are helping to remind us of the uplifting and ennobling qualities of Music, Art and Architecture. Let us, though, not forget to include Literature and Poetry!

❧

Written by John Uebersax

June 8, 2022 at 2:38 am

Posted in alienation, Art, Cognitive psychology, consciousness, Cultivation of the Intellect, Cultural psychology, Culture, Education reform, higher consciousness, Idealism, Literature, Love, Materialism, Media brainwashing, Moral philosophy, Philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, Renewing America, Scholarship, Self-culture, Social philosophy, Transcendentalism

Agape and the Social Inflection Point

HERE’S an analysis of the current state of society and of what needs doing:

❁ Our society seems headed towards an abyss. This has been going on for decades. Especially in the wake of Covid and now the war in Ukraine, people are dispirited, alienated and without much hope. The mentality is not good, and nobody has any solutions.

❁ Politics and government will not fix this. Indeed, political dysfunction is a large part of the problem.

❁ Therefore change must come at a cultural level, and first with individual consciousness. We need a change in individual mentality that will lead to constructive, creative action to transform society.

❁ For such a transformation to occur, it would help to have as many people as possible undergo the same change of consciousness. This supposes we’re talking about eliciting energies and forms of consciousness that are (1) instinctive and natural, and (2) common to all people.

❁ In order to have the most force and effectiveness, such a transformation of consciousness would ideally have a ‘contagious’ nature. We’d like it to spread ‘exponentially’.

❁ The human impulse of agape (charity/caritas, unselfish love, love of humanity) satisfies the criteria of being universal, instinctive, powerful, and stimulating creative energy.

❁ Agape towards another goes beyond trying to help meet their material needs. It aims to edify the other, to elevate their spirit, to help them on the ultimate life quest of finding meaning, moral virtue, and happiness.

❁ And implicit in all we have said so far, the highest moral development (aside from love of God) is to direct ones life towards edifying and morally uplifting others. So if we want to show the most agape love for another, we should seek most of all to help them show agape love for others. That is the agape chain reaction.

❁ Imagine, then, a society where each person sees it as their main social duty not only to exhort and uplift others, but to exhort them to discover their true self in uplifting others.

❁ Imagine a nation where each person is a Socrates. Where, instead of arguing with each other, each trying to change the opinion of the other on some matter to conform more closely to ones own opinion (which, properly understood, is a subtle form of coercion or even aggression — because we are trying to limit the freedom of the other), our main purpose is to remind the person to seek their true self. This, I believe, is related to the principle psychologist Carl Rogers called ‘unconditional positive regard.’

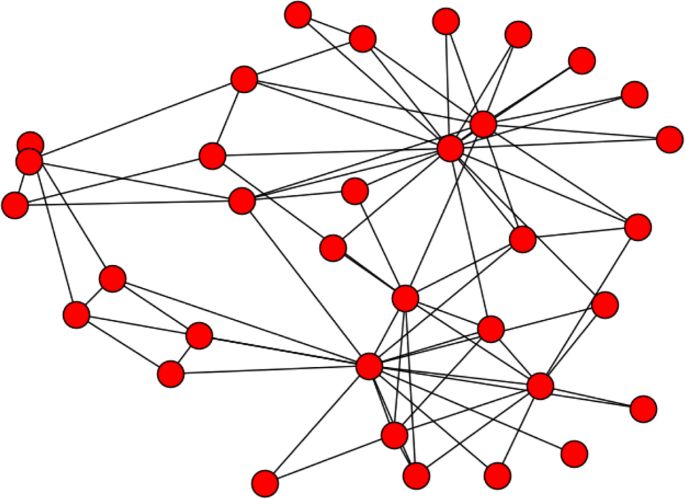

What we’re talking about is an inflection point, a change from a negatively oriented society to a positively oriented one. Imagine society as a network of interactions between nodes, each node being an individual. Negative interactions breed more negative interactions, and the same with positive ones. There are two ‘basins of attraction’, to put it in the language of complex systems theory. What we’re looking for is a phase shift in a complex dynamic system.

Kant’s moral principle of the categorical imperative may be considered here. In order for an act to be moral, according to Kant, it must satisfy the criteria that we could consistently wish that all other people followed the same principle. The more having all people follow the rule would produce good outcomes, the more confidence we have that it’s a good moral choice for ourselves. If all people consistently sought to uplift and edify others, this would have immense positive benefit for society. Therefore we can be confident this is a good moral rule to follow in our own personal life.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

June 6, 2022 at 7:04 pm

Transcendentalism. Reading.

“The mind, once stretched by a new idea, never returns to its original dimensions.” ~ Ralph Waldo Emerson

THIS is just a temporary post. In coming weeks, I’ll add material on two subjects: (1) Transcendentalism and (2) self-culture by reading quality books. Motivating this is my belief is that government and politics are inadequate to meet the challenges faced by society today. Instead what we need is a raising of collective consciousness. To some those two words may sound vague, but they actually means something real and definite. We are at a point in history where, to move forward as a species, we need a new way of understanding ourselves — as individuals, in relation to each other, and in relation to the planet.

To change consciousness may seem a daunting, even impossible task. But we have good reason for hope: because all human beings hold in their hearts both the hope of a better world, and an understanding of how that better world would be. Each of us contains the same blueprint for a good society; we merely haven’t yet learned to communicate and cooperate in ways to make that plan a reality.

This is the great task of the generation of young adults today, and of generations to come. A place to begin is to learn what the last great generation of Idealists had to say on the subject. Let us stand on the shoulders of giants, and then aim to make further progress.

Shortly I hope to supply a guide and links to relevant writings on American Transcendentalism. For now, below is a list of related articles on this blog (many contain bibliographies with more material).

p.s. The invariably asked question is “What is Transcendentalism?” The truth is, Transcendentalism cannot be defined. Ultimately, it refers to a level of consciousness which is, on the one hand, familiar, but, on the other, difficult to attain in the modern world. It involves the integration of our existence as material beings with simultaneous awareness of transcendent, eternal truths of which we also have innate knowledge. What was called Transcendentalism in the 19th tradition was called Idealism in preceding centuries. In the West this philosophical tradition goes back to Plato and beyond; and we can find counterparts in Eastern philosophy and religion.

John Uebersax

❧

❁What is American Transcendentalism? (Includes reading list)

❁Transcendentalism as Spiritual Consciousness

❁Selections from Emerson’s Essay ‘Intellect’ (1841)

❁John Sullivan Dwight: The Religion of Beauty (1840)

❁Abraham Maslow: How to Experience the Unitive Life

❁Beyond the Pyramid. Being-Psychology: Maslow’s Real Contribution

❁The Emersonian ‘Universal Mind’ and Its Vital Importance

❁James Freeman Clarke — Self-Culture by Reading and Books

❁‘The Sacred Marriage’, by Margaret Fuller

❁Culture in Crisis: The Visionary Theories of Pitirim Sorokin

❁Pitirim Sorokin: Techniques for the Altruistic Transformation of Individuals and Society

❁Thoreau and Occupy Wall Street: Life Without Principle

❁The Occupy Movement, Agrarianism, and Land Reform

❧❧

Written by John Uebersax

June 2, 2022 at 3:37 am

Robert F. Kennedy’s Speech, The Mindless Menace of Violence, and its Resonance Today

“Only a cleansing of our whole society can remove this sickness from our souls.”

THIS speech of Robert F. Kennedy, ‘The Mindless Menace of Violence’, should be read, listened to and watched by all Americans today. It’s not only arguably the finest speech of his career, but one of the great political speeches of the 20th century, and perhaps of all time. Most importantly, it bears special relevance to our current situation in America, and carries even greater urgency now than when it was delivered.

Kenned gave the speech in Cleveland on April, 5, 1968, the day after Martin Luther King was assassinated. He’d made briefer remarks in Indianapolis the evening before. The Indianapolis speech is more widely known — but to compare the two speeches is pointless. They could be viewed as single speech, as though if at the first one’s end he said, “And now let us pause, grieve and reflect on this tragedy, and I will continue tomorrow.”

Many vital themes are woven together in this short and moving speech: that American culture is saturated with violence, where this violence comes from, the sense of community it has destroyed, and, most importantly, how this sense can be restored.

He refers repeatedly to the shortness of life and how this makes the message of overcoming violence even more urgent — and one cannot help feel that he somehow sensed his own time was growing short. Less that two months later, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles, consecrated these words with his own blood.

❧

On the Mindless Menace of Violence

Speech of Robert F. Kennedy delivered at the Cleveland City Club, Cleveland, Ohio, April 5, 1968.

Mr. Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, I speak to you under different circumstances than I had intended to, just 24 hours ago.

But this is a time of shame, and a time of sorrow. It is not a day for politics. I have saved this one opportunity — my only event of today — to speak briefly to you about the mindless menace of violence in America which again stains our land and every one of our lives.

It’s not the concern of any one race. The victims of the violence are black and white, rich and poor, young and old, famous and unknown. They are, most important of all, human beings whom other human beings loved and needed. No one — no matter where he lives or what he does — can be certain whom next will suffer from some senseless act of bloodshed. And yet it goes on and on and on in this country of ours.

Why? What has violence ever accomplished? What has it ever created? No martyr’s cause has ever been stilled by an assassin’s bullet. No wrongs have ever been righted by riots and civil disorders. A sniper is only a coward, not a hero; and an uncontrolled or uncontrollable mob is only the voice of madness, not the voice of the people.

Whenever any American’s life is taken by another American unnecessarily — whether it is done in the name of the law or in defiance of the law, by one man or by a gang, in cold blood or in passion, in an attack of violence or in response to violence — whenever we tear at the fabric of our lives which another man has painfully and clumsily woven for himself and his children — whenever we do this, then whole nation is degraded. “Among free men,” said Abraham Lincoln, “there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet; and those who take such appeal are sure to lose their case and pay the cost.”

Yet we seemingly tolerate a rising level of violence that ignores our common humanity and our claims to civilization alike. We calmly accept newspaper reports of civilian slaughter in far off lands. We glorify killing on movie and television screens and we call it entertainment. We make it easier for men of all shades of sanity to acquire weapons and ammunition that they desire.

Too often we honor swagger and bluster and the wielders of force. Too often we excuse those who are willing to build their own lives on the shattered dreams of other human beings. Some Americans who preach nonviolence abroad fail to practice it here at home. Some who accuse others of rioting, and inciting riots, have by their own conduct invited them. Some look for scapegoats; others look for conspiracies. But this much is clear: violence breeds violence; repression breeds retaliation; and only a cleansing of our whole society can remove this sickness from our souls.

For there is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly, destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night. This is the violence of institutions; indifference, inaction, and decay. This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colors. This is a slow destruction of a child by hunger, and schools without books, and homes without heat in the winter. This is the breaking of a man’s spirit by denying him the chance to stand as a father and as a man amongst other men.

And this too afflicts us all. For when you teach a man to hate and to fear his brother, when you teach that he is a lesser man because of his color or his beliefs or the policies that he pursues, when you teach that those who differ from you threaten your freedom or your job or your home or your family, then you also learn to confront others not as fellow citizens but as enemies — to be met not with cooperation but with conquest, to be subjugated and to be mastered.

We learn, at the last, to look at our brothers as alien, alien men with whom we share a city, but not a community, men bound to us in common dwelling, but not in a common effort. We learn to share only a common fear — only a common desire to retreat from each other — only a common impulse to meet disagreement with force.

For all this there are no final answers for those of us who are American citizens. Yet we know what we must do, and that is to achieve true justice among all of our fellow citizens. The question is not what programs we should seek to enact. The question is whether we can find in our own midst and in our own hearts that leadership of humane purpose that will recognize the terrible truths of our existence.

We must admit the vanity of our false distinctions, the false distinctions among men, and learn to find our own advancement in search for the advancement of all. We must admit to ourselves that our own children’s future cannot be built on the misfortune of another’s. We must recognize that this short life can neither be ennobled or enriched by hatred or by revenge.

Our lives on this planet are too short, the work to be done is too great to let this spirit flourish any longer in this land of ours. Of course we cannot banish it with a program, nor with a resolution.

But we can perhaps remember — if only for a time — that those who live with us are our brothers, that they share with us the same short movement of life, that they seek — as do we — nothing but the chance to live out their lives in purpose and in happiness, winning what satisfaction and fulfillment that they can.

Surely this bond of common fate, surely this bond of common goals can begin to teach us something. Surely we can learn, at least, to look around at those of us, of our fellow man, and surely we can begin to work a little harder to bind up the wounds among us and to become in our hearts brothers and countrymen once again.

Tennyson wrote in Ulysses:

That which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Thank you, very much.

❧

Discussion

Let us draw attention to several points in the speech that bear direct relevance to our present situation in America.

First, we are as a people in a state of complete disunity. Ironically, just as he states, the one thing that we have in common — and in that sense ‘unites’ us — is precisely our disunity. We have each and all succumbed to the spirit of division, contention and party. Political participation consists of nothing more than reacting emotionally to biased and distorted news, and hostile comments on social media.

Second, this is suicidal. Our welfare, hope and survival as a people depend on our unity. A connecting bond, a sense of unifying purpose, is not a luxury, but a necessity.

Third — and here we begin to see the genius of the speech — Kennedy tells us that the bond that ought to unite us, the one that makes most sense given our peculiar history and situation in the world, is to forge a society that transcends divisiveness, hostility, and violence. We remain the freest people in human history. This is not because of exceptional virtue, but because history and geography has blessed us with a land of vast natural resources, immense variation, and freedom from threat of foreign invasion. We have the resources to feed, employ, educate, and maintain the health of all. The only thing stopping us is our own folly and perversity.

Fourth — and here again is an immensely important point — the way to achieve this unifying bond of common purpose is not through legislation or government, but “to find in our own midst and in our own hearts that leadership of humane purpose.” Much is said in these few words. To find something means it already exists. There is something already in our hearts that will lead us. It is a true conscience, one founded on love, wisdom and Eternal Verities — and is by no means to be confused with a political doctrine or ideology, no matter how high-minded that ideology may sound.

Finally, Kennedy suggests that this inner truth of our hearts is intimately connected with an awareness of a certain fragility of human life.

Life is short, fraught with peril. If we respond to this with fear and defensiveness, we withdraw into narcissism and folly, seeking to insulate ourselves from the ‘terrible truths’ with walls of illusion. Our political beliefs, more often than not, are manifestations of this defensive, constructed reality; and we respond to attacks on our defensive illusions by lashing out, fearing, hating and retreating further into delusion.

But Kennedy reminds us there is another way. That is see that the fragility of life actually unites us with all people. It causes us need each other, and makes things like respect, compassion and charity more deeply meaningful. When we find again and are guided by our heart of hearts, there will be no time for or interest in violence or contention.

Let us then take his inspired words to heart in this time of greatest need. Let each one begin an earnest search into his or her heart to find that “leadership of human purpose.”

Sources

I would encourage everyone to not only read, but listen to and watch the speech. Unfortunately there is variability in versions offered online, so some caution must be exercised.

The best transcript I’ve found is from the University of Maryland. This is closer to Kennedy’s actual words than what is found on the JFK library website.

The best audio version I’ve found is from the City Club of Cleveland.

While the entire speech was filmed (by multiple cameras), I have so far not found any version that has not edited out important parts. This version is incomplete, but is high quality and succeeds in expressing Kennedy’s facial expressions and emotions better than others — things which are as important here a the words themselves.

❧❧

Written by John Uebersax

May 30, 2022 at 8:49 pm

The Four Psychological Responses to Great Social Crises

THE sociologist Pitirim Sorokin conducted extensive research on cultural mentalities, including comprehensive historical studies (Sorokin 1957, 1985). He found that major shifts in mentality are often precipitated by the occurrence of multiple crises and catastrophes — wars, plagues, famines, natural disasters, revolutions, etc. He also noted that the crises developing in the 20th century — which he correctly predicted would worsen — would likely necessitate or precipitate a major change in cultural mentality. Hopefully, in his view, this would be a shift from radical materialism to a more idealistic, altruistic, transcendent and integrated mentality.

One of his papers (Sorokin, 1951) identified four responses to “mass-suffering and mass-frustration in social calamities.” These apply at both the individual and collective psychological level. In brief terms, the four responses are as follows:

Passivity. Faced with crises they are powerless to oppose or remedy, individuals succumb to a state of passive resignation, depression, and hopelessness. This is probably the most widespread response.

Degradation. Here the individual responds by becoming more aggressive, brutal and selfish. In the case of wars and revolutions, the person ‘identifies with the aggressor.’ The world is accepted as a bellum omnium contra omnes. Virtue is abandoned, and escape and solace are sought in various vices and follies: sex, addiction, avarice, fanaticism, chronic anger, etc. Demoralization leads to self-loathing, and further self-destructive flight into vice and delusion.

Heroism. A few individuals endowed with extraordinary resilience and talent seek to defiantly meet the social challenges with heroic feats of creativity. In the artistic realm, Beethoven serves as an example, and Edison in the scientific/technical arena.

Moral reformation. The most productive response in Sorokin’s opinion, is exemplified by the lives of great saints and reformers who appear throughout history, often in times of crisis and catastrophe. However, while great figures like St. Francis of Assisi and Mohandas Gandhi are rare, the same process of moral reformation they underwent is played out less visibly in the lives many more ‘ordinary saints.’ In each case, the trajectory of moral reformation is basically the same: first the individual acknowledges the seriousness of their own moral failings, admitting and rejecting the innate selfishness and aggression of lower human nature (repentance; metanoia). Then, by characteristic practices such as asceticism, meditation and prayer, they seek to purify themselves from these failings, and then to grow in altruism and spirituality. During this process, they reject former social roles built on egoistic values and develop new ones based on spiritual values — often going through a period of relative (or sometimes complete) isolation in between. Finally, with egoism conquered, they direct their energies with clear purpose and absolute focus on altruistic, charitable and creative activities aimed at improving the lives of others. Part of this altruistic activity may involve helping others to achieve this same moral transformation.

When, perhaps under the stimulus of some exemplary figure like St. Francis or Gandhi, many individuals in society undergo this moral reformation, the mentality of the entire culture shifts from the materialistic and egoistic to the altruistic.

In short, it was Sorokin’s hope and vision (see especially, Sorokin 1948, 1954) that, as the crises of the 20th century continued and worsened, this transformation of culture would occur. He argued that not only is this possible — as this transformation has occurred in the past — but it may be necessary today for the continuation of the human race.

Yet, even apart from the broader cultural significance, it must be remarked that this form of altruistic and spiritual transformation is something of supreme value for the individual. Repentance and conversion are not an onerous burdens, but gateways to joy, self-realization, and liberation of the divine potentials — the arrival at our full stature as human beings. It is within our power, then, as individuals, to cognitive reframe the meaning and significance of the crises of our times. In crises lay great opportunities.

References

Sorokin, Pitirim A. The Reconstruction of Humanity. Beacon Press, 1948.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. Polarization in frustration and crises. Archiv Für Rechts- Und Sozialphilosophie, vol. 39, no. 2, 1951, pp. 145–163.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. The Ways and Power of Love: Types, Factors, and Techniques of Moral Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1954; repr. Templeton Foundation, 2002. [ebook]

Sorokin, Pitirim A. Social and Cultural Dynamics. Revised and abridged in one volume by the author, Transaction Books, 1957, 1985. (Originally published in four volumes, I–III, 1937; IV, 1941.)

❧

Written by John Uebersax

May 6, 2022 at 1:38 am

Posted in consciousness, Cultural psychology, Culture, Gandhi, higher consciousness, Humanism, humanistic psychology, Idealism, Love, Materialism, Moral philosophy, Pitirim Sorokin, Psychology, Social philosophy, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values

Tagged with altruism, catastrophes, cultural mentality, ethics, moral renewal, social crises, social transformation

Gods in Ruins

NEEDED at this point in history is a great leap forward in human consciousness, a new way of looking at ourselves — as individuals and collectively. This weekend I had a glimpse of what this leap might look like, and am still trying to sort it out, but I’ll attempt here to convey the essence.

The idea is suggested by a phrase from Ralph Waldo Emerson, “We are gods in ruins.” This sentence has quite a bit of meaning. First, we are gods. That’s plausible enough. Christians and members of other religions believe that human beings are made in God’s image and likeness. Each person is an image of God, and has an eternal souls and has unlimited, divine potentials.

But, Emerson added: in ruins. We may have the potential to be divine, but our thoughts and actions are, with rare exceptions, anything but that.

But consider how different the world would be if each person remained constantly aware that (1) all other persons are divine; and (2) each person was falling short of their divine potential.

Now let’s now add love to the formula. Each person has the potential to love another human being in a divine and godly way. We can recall times when we’ve felt loved and can remember the many and immense benefits this feeling has. And we ourselves can, in theory, love any other human being in this way, producing the same divine positive effects. Your love can work miracles in another person’s life, and theirs can work miracles in yours. Few things if any make us feel better than to be loved. You have the power to produce that feeling in any one of 7 billion other souls on the planet; and there are 7 billion souls who have the ability to have that effect on you.

Consider what I’m saying here. What if, instead of love, we were talking about money. Suppose I said that you have the ability to make any one (and perhaps any number) of the 7 billion people on this planet a millionaire. And 7 billion people had the power to do that for you. What a colossal waste it would be, then, if we had this power and never used it, such that the vast majority of the world’s population lived in poverty!

One might say that surely humanity is not so foolish as to let that happen. Yet consider that love is more valuable than money. A rich person without love is miserable, whereas a poor person with love is happy. The greatest advantage money has, in fact, is to produce circumstances favorable for the flourishing of love. Yet, for the most part, money is not needed for love. Seen in this way it is incredible how we are ignoring this vast ‘natural resource’ of love. It is being utterly wasted.

Now let’s put the two ideas together: the notion of ‘gods in ruins’ and the untapped potential of love. What if each person habitually thought as follows:

- Each other person on the planet is an image of God.

- Each other person has divine, untapped potentialities, a principle one being the capacity for divine love and altruism.

- We are all falling short of this potential.

- What if I could do something — anything — to help other people be restored to their divinity and use their divine potentialities? How could I better employ my time and energies than to do this? What would make me feel more satisfied?

- What is more divine than to love divinely? What if I could do something to help another person love divinely?

First we should note that this view is more true than our ordinary consensual concept of what it is to be human. If we are gods in ruins, then we should think of ourselves as such. It would make us less egoistic, anxious, foolish, selfish, frivolous, scattered, and angry. We would soon discover many ways to help other people. And also consider how, were such thinking to become the norm, it would change our perception of society. What if we had a culture in which it was pre-supposed that other people value the image of God in you, and are not only willing but eager to help you realize it? It seems clear that a society based on these values would be vastly superior to our present one, and would reduce or eliminate many of the crippling social problems we now face (beginning with war).

For millennia religions have taught us that we are divine beings — and humanity has chosen to pretend otherwise. Now we may have no choice but to rise to our full stature.

❧

Written by John Uebersax

May 2, 2022 at 5:00 am

Posted in Anti-war, consciousness, Cultural psychology, Culture, Culture of peace, higher consciousness, Humanism, humanistic psychology, Idealism, Love, Materialism, Peace, religion, Social philosophy, spirituality, Transcendentalism, Values, War

Tagged with altruism, ethics, social transformation

The Immortal I

The Immortal I

You must be logged in to post a comment.